In the olden days, women across Lao PDR inherited their weaving skills from their mothers, mostly for their own use. Weaving was also a communal activity, allowing for social interaction with other women in their communities. With the advent of mass-produced industrial textiles, the traditional art of silk and cotton weaving has been pushed back mainly into the domain of healing rituals and ceremonial purposes.

Aside from their roles in major rites of passage such as birth, puberty, marriage and death, some traditional weaving products have also reached the market for tourist as knick-knacks and souvenirs. Gradually, in the last decade, rural Laotian traditional textile art is now making a comeback. Younger weavers are becoming master artisans and entrepreneurs, making waves in the arts market, and creating a new livelihood strategy from centuries-old traditions.

One such women is Sykai Phonthilath, age 35, crafting her magic at her loom with other women in a workshop in Luang Prabang. Her mother, Papeng, age 59, who sits at another loom nearby, taught her the weaving skills at the age of eight. Almost three decades later, Sykai became a master weaver, creating original designs for scarves, wall hangings and skirts, with a flourishing product line that is sold in boutique shops.

Sykai’s weaving monthly income of around US$350 – almost three times the minimum wage in Lao PDR – was enough to pay for her 16-year old daughter’s stay in school and beyond. She hoped her daughter would be the first woman in her family to attend university, something that was not possible due to poverty.

“I’m happy she can use her income from weaving to make her family’s life better than it was in the past,” said Papeng.

Poverty in Lao PDR

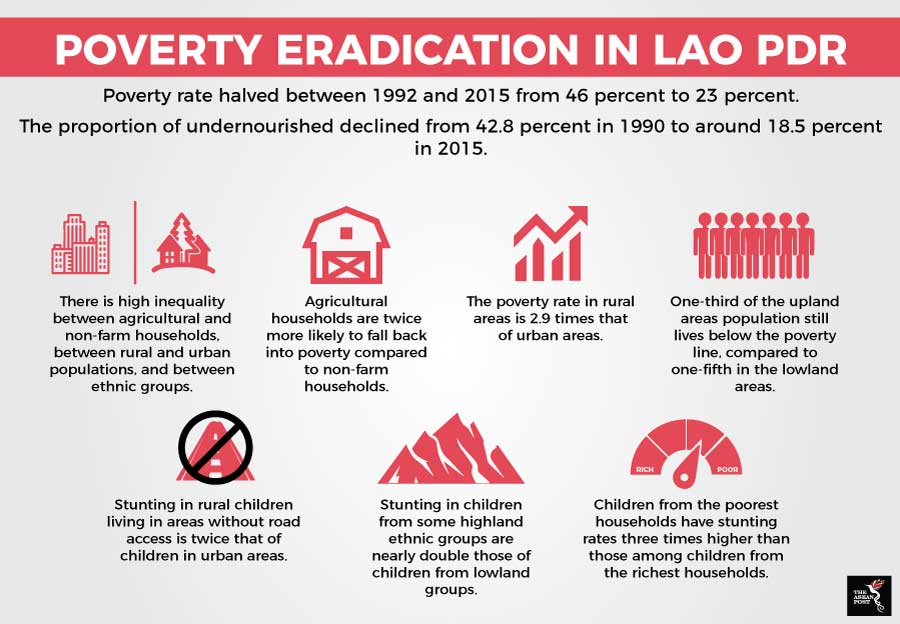

Despite halving the poverty level from 46 percent in 1992 to 23 percent in 2015, the challenges to reduce the number of people living below the poverty line in Lao PDR remain, with a significant proportion of the population at risk of falling into poverty. According to Lao’s voluntary national review on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, agricultural households are twice more likely than non-farm households to fall back into poverty. This is mainly due to their high vulnerability to shocks and inability to mitigate risks such as health risks as insurance coverage and social protection are limited.

People living in rural areas are also more likely to be living below the poverty line, with the rural poverty rate 2.9 times that of urban areas. More than a third of the population in upland areas are still living below the poverty line compared to only a fifth of the lowland population.

Source: Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform.

Source: Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform.

By women, for women

Bringing their weaving products to and triggering the demand in the market would not have been possible for women like Sykai and Papeng without the work of local non-profit organisations and social enterprises such as The Traditional Arts and Ethnology Centre (TAEC) and Ock Pop Tok. These entities not only provide support and training for weavers to access the market, but also loans and employment.

Ock Pop Tok (translated to ‘East Meets West’ in Lao), founded on the principles of fair trade, sustainable business practices and ethical fashion, started in 2000 with five weavers. In less than two decades, it has grown to 500 artisans countrywide, almost 50 of which are master weavers at the Living Crafts Centre and nearby villages. 50 percent of its profits go to the Village Weaver Projects, which is a series of initiatives to create economic opportunities for rural artisans in 13 provinces.

Like Ock Pop Tok, TAEC is also working with over 600 artisans, 95 percent of whom are women weavers or embroiderers from rural ethnic groups. The organisation helps commercialise the old tradition by granting small loans and training women on product design and small business practices.

Impact evaluation studies often find that empowering women benefits not only themselves but also their households and communities. Breathing new life into old traditions such as the art of weaving by leveraging on the ethical consumption market, through social enterprises and the use of technology such as online shopping could revive a dying tradition and bring more young people forward to claim it.

Related articles:

Refashioning the fashion industry

Celebrating Indonesia’s cultural heritage, batik