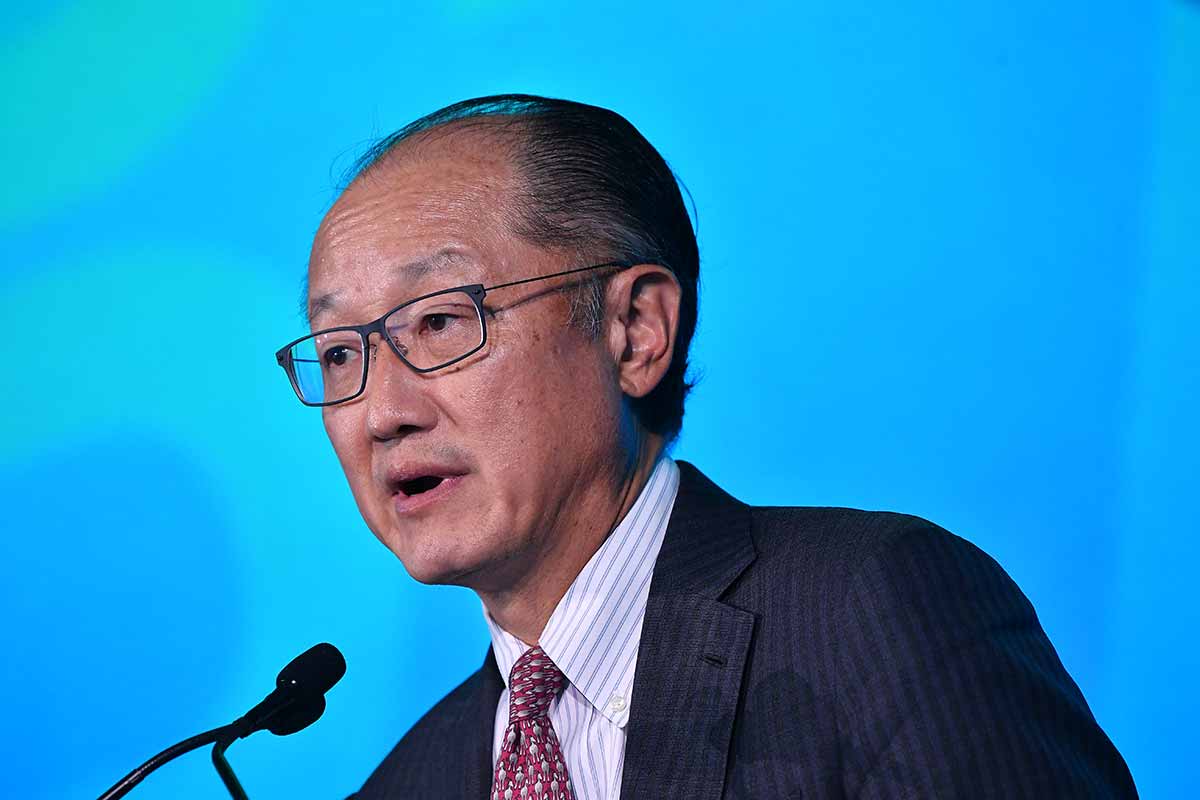

Jim Yong Kim’s sudden resignation as president of the World Bank Group (WBG) offers an opportunity to reflect on the direction, legitimacy, and effectiveness of that 75-year old institution. Like other multilateral institutions, the Bank in recent years has been criticised for its elitism and for championing outmoded models of economic globalisation that have failed to deliver broad-based benefits. It has also become another staging ground for the geopolitical great-power rivalry between the United States (US) and China.

Recognising this, finance ministers and central bank governors from the Group of Twenty (G20) established a commission in April 2017 to recommend reforms to the global financial architecture and the international financial institutions. And at a G20 meeting in October 2018, the commission issued a report outlining steps “to create a cooperative international order for a world that has changed irreversibly.”

The proper mission of multilateral development finance institutions is to help solve urgent, large-scale problems in the developing world. For example, we are currently witnessing the largest urban expansion in history, and managing it will require a doubling of the global infrastructure stock within the next 15 years. Multilateral institutions also have a role to play in addressing the great expansion of Africa’s population, and in laying the foundation for sustainable, decarbonised economic growth across the developing world. Failing that, the world should expect to see more migration, unemployment, frustration, and anger in the years ahead.

This is the context in which the next WBG president will be selected. Not surprisingly, the organisation’s Board of Executive Directors hopes to find a candidate who is capable of effective leadership and management, with a compelling vision, a commitment to multilateralism, and diplomatic communication skills (read: “politically savvy”). The candidate should be prepared to implement already agreed strategies, embodied in the WBG’s previously published “Forward Look” and the “Sustainable Financing” papers.

But the most important criterion, in our view, is that the candidate should embrace the WBG’s mission in all of its ambition and scale, and follow through on the recommendations in the recent G20 report. The WBG president’s job was redefined in 2017, with the introduction of a Chief Executive Officer. Under this new arrangement, the president should be freed up to focus on strategy (for example, how best to deploy a recent capital increase), Board relations, and partnerships.

In the absence of a standard leadership-selection process, multilateral institutions have developed their own methods over time. For example, the Inter-American Development Bank has a double majority system, whereby the winning candidate must gain a majority of shareholder votes, as well as an absolute majority of votes from regional governors. In the United Nations (UN), the General Assembly selects the secretary-general on the recommendation of the Security Council. For the newly created Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the president must receive 75 percent of the votes. In each case, the process is designed to give the world’s major powers their due say, while preventing any country from dominating the agenda entirely, thereby maintaining the spirit of multilateralism.

At the WBG, however, the winning candidate simply has to get the most votes. Practically speaking, the president has always been an American, thanks to an informal bargain between the US and Europe, whereby the Europeans back the WBG candidate favoured by the US, while the US supports a European to lead the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – which has a similar simple-majority voting system. To be sure, the US cannot veto a candidate for WBG president (as it can with a candidate for UN secretary-general). But it would be foolhardy for any candidate to campaign without at least an implicit US endorsement.

This leaves a range of options for choosing the next WBG president. The US could select an American who appeals to other countries: Kim, for example, touted his Korean origins during his 2012 campaign for the post. It could select a dual national or an immigrant, such as former WBG President James Wolfensohn, an Australian who became a US citizen. Or it could back a non-American candidate from an allied country. What is important is that the nominee enjoys the trust of the US and most other countries, and can reconcile countries’ diverse interests in a true spirit of multilateralism. Nationality, per se, is not a prerequisite.

But gaining the support of other countries is just one requirement. The successful candidate should also have support from other stakeholders. At the UN, candidates publish vision statements and responses to questions from civil-society organisations, and participate in a global town hall event. A WBG presidential candidate should embrace such transparency and extend it to businesses and academia, in keeping with the institution’s commitment to empiricism and fact-based solutions.

When the Board selects Kim’s successor in April, we hope it does so in a way that contributes to the institution’s legitimacy and effectiveness. The WBG needs a trusted leader who understands the urgency and scope of the organisation’s mission. In fact, the WBG has never had a female president. There’s no better time than now to usher in fundamental change.

Homi Kharas is Interim Vice President and Director of the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution. Eswar Prasad is a professor at Cornell University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.