The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected that global warming is likely to reach 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2030. This is projected to bring about changes in the climate and natural systems, including changes in the frequency and intensity of weather events, sea-level rise, habitat and range loss, biodiversity loss, water scarcity and more.

Every aspect of human life including health, livelihoods, food, security and economic growth is expected to be impacted. This is especially true in Southeast Asia, where climate change is threatening to disrupt the remarkable expansion of its economies and undo the hard-earned achievements of its sustainable development.

The Southeast Asian region has been ranked as one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change due to the urbanisation and concentration of its economic capitals along coastline areas and within deltas, as well as its economic reliance on agriculture and natural resources. According to the United Nations (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), worsening climate conditions in the region is a key driver for the increase in the number of people suffering from starvation.

Agriculture at the front line

In 2018, extreme seasonal rains and flooding in the north, an extended dry season in Indonesia, and increasingly frequent storm events from tropical depressions to super typhoons, took a toll on the region’s economy. Climate events such as these resulted in the destruction of paddy fields and farms in the region’s crucial agricultural heartlands.

According to Carolyn Rodrigues Birkett, Director of FAO’s Liaison Office in Geneva, in developing countries, the agriculture sector absorbs about 22 percent of the total damage and losses caused by natural hazards, 84 percent if one considers drought alone.

“No sector is more sensitive than agriculture and no solution to climate change and disasters will be complete without agricultural inputs,” she said at the opening of a panel discussion on Integrating Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Risk Reduction.

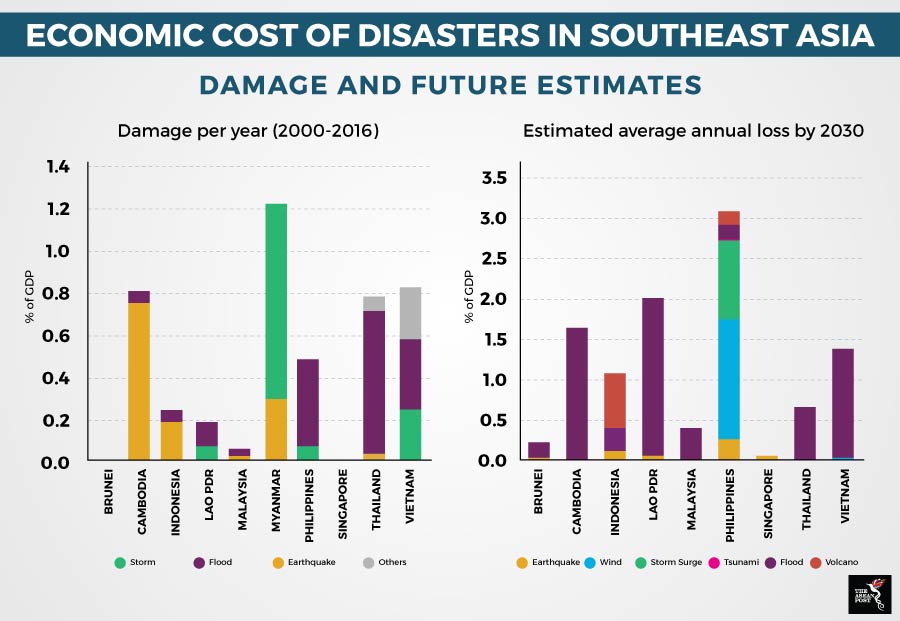

Source: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction

Source: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction

Farmers are at the front line of climate change, staring down droughts, extreme rainfall, flooding and storms to continue producing food for everyone. But what happens if farmers cannot absorb the damages and are forced to discontinue food production? In Indonesia, for example, around 93 percent of Indonesia’s farmers are small family farmers for food crops such as rice, corn and cassava, as well as cash crops like palm oil and rubber. Many of them struggle with poverty, with almost one fifth of them living below the national poverty line.

Mitigating climate damage to key food crops

Towards building farmers’ resilience, the region’s governments have started moving toward setting up risk transfer mechanisms, such as insurance for the agricultural sector at different levels. In the region, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Cambodia and Myanmar have tested and developed specific models of government-subsidised insurance-based schemes to protect against the worst damage due to extreme weather events, all at different levels of implementation.

In Indonesia, after a few pilot projects, the government there launched the National Agricultural Scheme for rice farmers in 2015. However, despite the strong participation of the public sector where 80 percent of premiums were subsidised locally, the penetration of such financial instruments is still low while coverage for crops other than rice is limited.

Agricultural Insurance Specialist, Margherita Bavagnoli said that the main challenges are not only to increase the uptake from farmers, but also to develop a strategy for long-term sustainability of those instruments.

“Obviously, financial burden is one of the reasons for low penetration. However, many other variables are seen as playing almost equal importance in the success or failure of such products. As long as farmers do not fully understand the importance of such products, and the private sector does not play an active role in creating a market, such measures will only remain a social protection measure provided by governments. This is hardly sustainable in the long run,” explained Bavagnoli.

The IPCC has warned that rice yields and quality will likely face reduction. This is true for most other staple foods such as maize, wheat and other cereal crops. Governments, the private sector and other stakeholders need to help farmers continue to produce and be profitable as the climate worsens, without whom, there will be no food on our tables.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 19 October 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles:

Food price and import in the wake of Mangkhut

Weather beating for rice production