A large portion of the population in Southeast Asia do not have proper information on the air they breathe every day.

Released on Tuesday, the 2018 World Air Quality Report from Greenpeace and AirVisual found that while 95 percent of Southeast Asian cities surveyed exceeded the World Health Organization’s (WHO) annual exposure guideline, the lack of data from four countries makes it harder for their citizens to be well informed about the daily health risks they face.

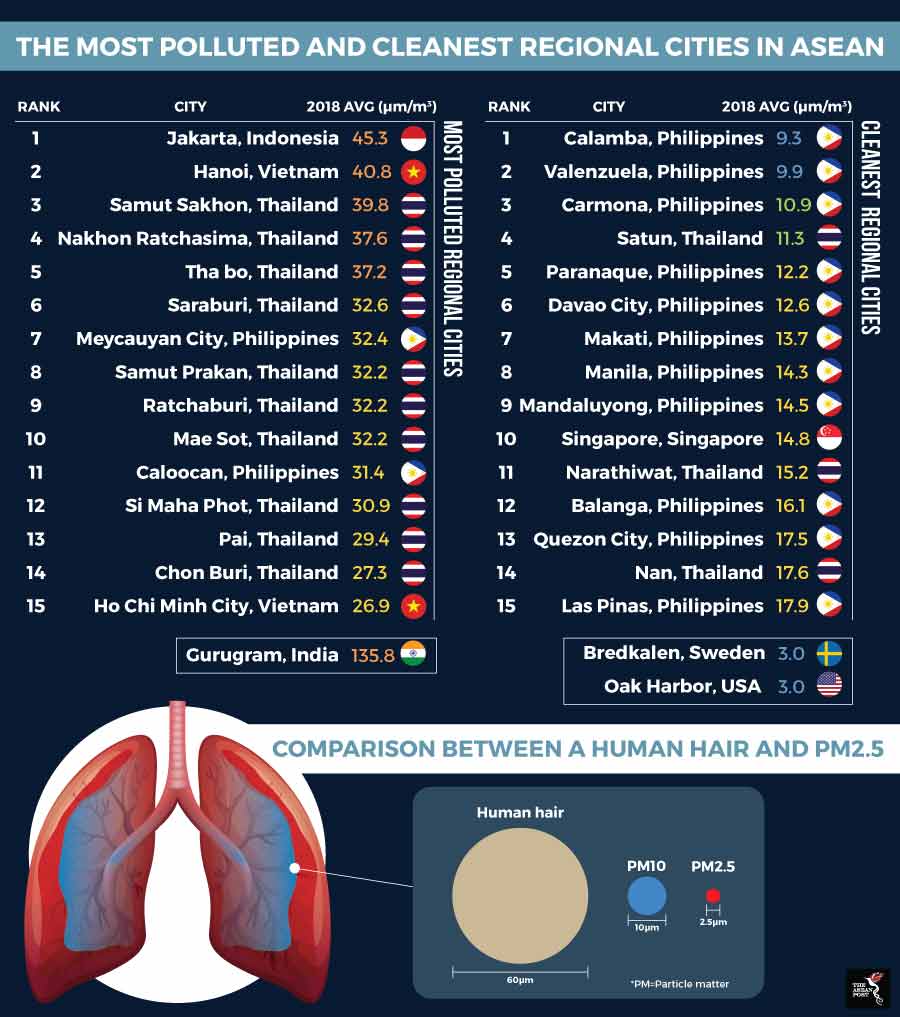

The report analysed air pollution readings from 3,000 cities around the world, with the data derived from public monitoring sources which measure and publish PM2.5 concentrations in real-time or near real-time. These sources include government monitoring networks and validated data from air quality monitors operated by private individuals and organisations. Only 145 monitors from ASEAN were included in the report.

PM2.5 refers to particulate matter (PM) smaller than 2.5 micrometres (one millimetre is equal to 1,000 micrometres) and is widely regarded as the pollutant with the most health impact of all commonly measured air pollutants.

Hanoi was found to have the worst air quality in ASEAN while Calamba in the Philippines had the cleanest air. However, the lack of data from Brunei, Lao PDR, Malaysia and Myanmar hampered researchers’ efforts and is a worrying fact for residents in these countries.

While stations in Thailand and the Philippines could provide data for 20 and 16 cities respectively, Indonesia – with a population of roughly 260 million people spread out across more than 17,000 islands – only had data for four of its cities. Vietnam, with a population of more than 90 million people, only had data for two major cities; Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh. There are at least 10 national stations and more than 50 municipal stations operating in Bangkok, but they do not release real-time data to the public.

“Local and national governments can help tackle the effects of air pollution by providing adequate monitoring and reporting infrastructure,” said Yeb Sano, Executive Director of Greenpeace South East Asia.

“What is clear is that the common culprit across the globe is the burning of fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – worsened by the cutting down of our forests. What we need to see is our leaders thinking seriously about our health and the climate by looking at a fair transition out of fossil fuels while telling us clearly the level of our air quality, so that steps can be taken to tackle this health and climate crisis.”

Dangers of PM2.5

While some areas may have stations which monitor other indicators such as PM10 or sulphur dioxide, they may not necessarily include PM2.5 – the deadliest form of air pollution.

The University of Chicago’s Air Quality Life Index defines PM as solid and liquid particles such as soot, smoke and dust that are suspended in the air. Common sources of PM include combustion from vehicle engines, industries and fossil fuel.

Due to its small size, PM2.5 – which is just four percent the diameter of a human hair – is able to penetrate deep into the human respiratory system, and from there to the entire body, causing numerous short and long-term health effects.

The WHO estimates that around seven million people die every year from exposure to PM in polluted air that penetrate deep into the lungs and cardiovascular system, causing diseases including stroke, heart disease, lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and respiratory infections. PM pollution is also associated with lower cognitive function, Alzheimer’s and dementia – making it all the more important that ASEAN’s citizens are fully aware of its effects.

Greenpeace stated that for children living in Jakarta and Hanoi, air pollution increases the risk of death from respiratory infections by 40 percent and asthma attacks by 20 percent. For adults, the risk of lung cancer increases by 25 to 30 percent and the risk of stroke doubles.

Previous indexes such as the Air Pollution Index (API), which is a combined reading of PM10 (particles with diameters smaller than 10 micrometres) and carbon monoxide, ozone, nitrogen dioxide and sulphur dioxide, are outdated and do not provide the most accurate representation of air quality any longer.

The WHO recommends an annual mean exposure threshold of 10 micrometres of PM2.5 per cubic meter, and although 95 percent of cities in Southeast Asia were found to be above the guideline, globally, 64 percent fail to meet the mark. All the measured cities in the Middle East and Africa exceeded this guideline, while in South Asia and East Asia, the number was 99 percent and 89 percent, respectively.

Apart from setting targets and timelines and creating action plans to bring air quality to acceptable levels, ASEAN has to do more to shift to clean renewable energy sources and sustainable transport systems. Strengthening emissions standards and enforcement for power plants, industries, vehicles and other major emissions sources will also help ASEAN breathe cleaner air.

Related articles:

Bangkok faces toxic smog battle