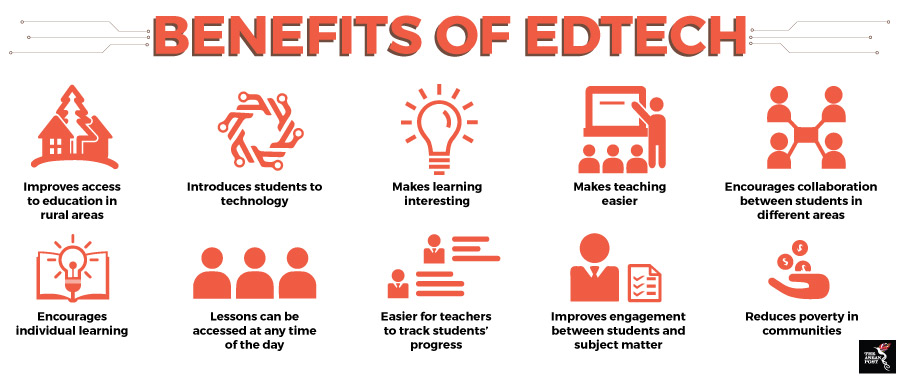

Education technology (edtech) is fast growing in Southeast Asia thanks to its learner-centric platform which breaks down geographical barriers such as access to infrastructure like schools and even transport.

Digital tools such as apps, eBooks, websites, quizzes, streaming media, online tutorials, videos and other materials are helping to pave new roads in education in Southeast Asia by providing quality content and lessons in places that were once inaccessible.

While companies such as HarukaEdu (Indonesia), Topica, (Vietnam), and Cialfo (Singapore) offer advanced courses, there are many others – such as Taamkru (Thailand), Ruangguru (Indonesia) and Classruum (Malaysia) – that provide lessons and tutorials for pre-schoolers and primary school children.

Taamkru, which offers gamified lessons for mathematics, science, and English, says that children who use its app over a 15-day period see an average improvement of 26.8 percent in their scores on the app.

Higher internet penetration rates and an ever-growing number of smartphone users has facilitated the rise of the edtech industry in Southeast Asia. Globally, the edtech market is projected to grow at 17 percent annually and is expected to be worth US$252 billion by 2020.

Edtech is particularly useful in large countries such as Indonesia which has a population of nearly 270 million spread out over more than 17,000 islands. A case in point is Ruangguru, Indonesia’s largest online platform for tutoring. The portal has over 80,000 registered qualified teachers; making it easier for its more than seven million users to get quality assistance from tutors via audio calls or chat boxes.

Many still denied proper education

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation’s (UNESCO) 2017-18 Global Education Monitoring Report, 264 million children were denied access to education in 2017. Only 83 percent of children who go to school at all complete elementary school and just 45 percent of students aged 15 to 17 will finish secondary school.

Tight budgets lead to a lack of proper infrastructure and trained teachers, which in turn leads to children not getting the quality of education they need to become skilled workers. Combined with the lack of emphasis placed on learning English, it is easy to see how some communities can find it hard to secure better paying jobs.

The problem is especially acute in rural Southeast Asia, where the lack of development and scarcity of trained teachers contributes to children not getting the education they deserve.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that the rural population in ASEAN member states will total 324.3 million or 47 percent of its entire population by 2025. Southeast Asia cannot afford to deny these children access to proper education. Failure to do so will risk leaving out a large portion of the potential workforce which could be contributing to the economy.

At the global level, the participation rate in early childhood and primary education was 70 percent in 2016 according to the UN – up from 63 per cent in 2010. The UN estimates that 617 million children and adolescents of primary and lower secondary school age worldwide or 58 percent of that age group are not achieving minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics.

While ASEAN’s average adult literacy rate (15 years old and above) is 94.9 percent according to the United Nations (UN), Lao is far below the average at 58.3 percent while Cambodia and Myanmar come in at 73.9 percent and 75.6 percent, respectively.

Edtech can help fill these gaps as well as meet the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 4, which is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all by 2030.

With all the recent advances made in technology, it is only natural that they are fully utilised to plug the holes in Southeast Asia’s education systems and ensure education for all.

Related articles:

Digital villages in rural ASEAN