The launching of Brunei’s biggest commercial paddy field later this year combined with higher yielding varieties of paddy are expected to help the country meet its rice self-sufficiency target in 2020.

The sultanate is embarking on a concerted effort to reach its rice self-sufficiency target of 11 percent by 2020 and wean itself off imports from Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam – which make up around 30,000 tonnes annually.

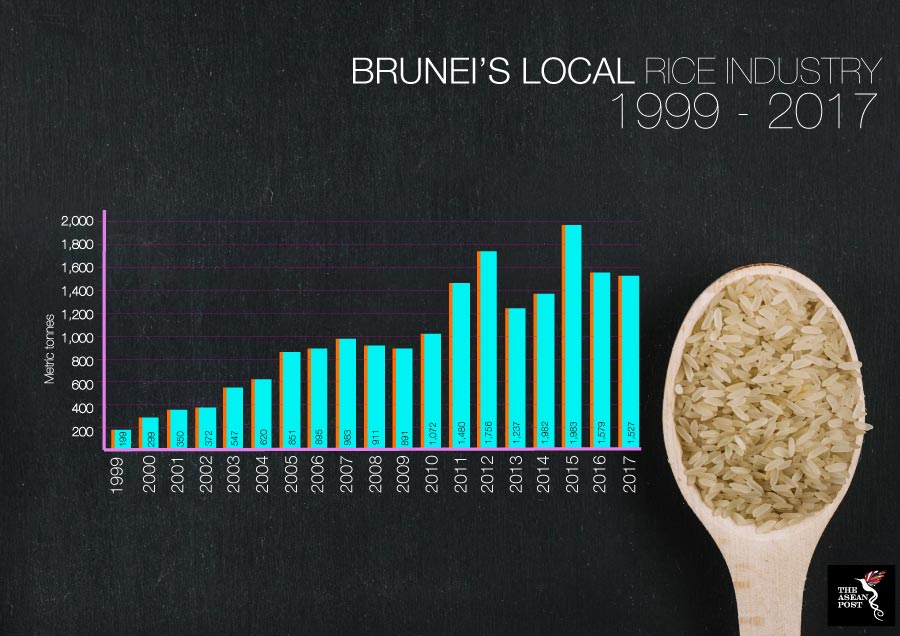

Once a thriving industry, Brunei’s rice farmers only produced 1,526 metric tonnes in 2017 – which accounted for 4.7 percent of national self-sufficiency. The percentage was 4.6 in 2016 and six percent in 2015, far behind its self-sufficiency numbers in other agricultural sectors such as vegetables and meat.

During a Legislative Council session earlier this month, Brunei's Minister of Primary Resources and Tourism said that while the country is almost self-sufficient in poultry and eggs, he admitted that reliance on foreign rice is still high. The country’s Legislative Council serves as its annual parliament and meets once a year in March to discuss national issues as well as review and finalise policies and budgets.

The 11 percent target for 2020 is a marked decrease from the original 20 percent target. Last year, the Ministry of Primary Resources and Tourism said it wanted local rice farmers to produce 7,700 metric tonnes by 2020 – which would have marked 22 percent self-sufficiency. Previously, the target was set at an ambitious 60 percent by 2015 – but the final figure was only four percent.

More land, better yield

Brunei’s low rice production should be set to change once a 500-hectare plot set aside in the Belait district gets off the ground in October and becomes the country’s largest commercial paddy field. According to local media reports, two other new sites in the Brunei Muara district are also expected to boost the total land area reserved for rice cultivation.

New strains of paddy will also help Brunei meet its target, as will upgrades and expansions of dams and other projects to improve irrigation and drainage systems which were recently announced.

Brunei’s Department of Agriculture and Agrifood (DAA) jointly developed a strain called Sembada (188) with Indonesia’s Biogene Plantation with a yield of six metric tonnes per hectare; nearly twice that of current local varieties. First planted last October, it was harvested last month. Final figures of its yield are still unconfirmed, but there are plans underway to plant the new strain across the country. Another hybrid, titith, is a tie-up with a Myanmar firm and is expected to produce eight metric tonnes per hectare.

Work is also being done with research institutes from China and the Philippines to produce higher yielding varieties and to maximise land utilisation. Last year, the Ministry of Primary Resources and Tourism said it was working to develop a strain which would yield 12 tonnes per hectare which if successfully planted, would see the country meet 30 percent of its rice needs.

Rice self-sufficiency not always an issue

In 1974, Brunei produced 37.5 percent of the rice it consumed – 6,348 tonnes. However, a rise in cheaper imports and a population surge led to the slow downfall of the local rice industry, and four years later, Brunei’s rice self-sufficiency stood at just 13.7 percent. Combined with more stable – and less laborious – jobs in the civil sector and burgeoning oil and gas industry, the country’s rice fields soon began to turn fallow.

Authorities are looking to revive the rice industry, and last year, set aside US$4 million for the national rice production programme to pay for subsidises for seeds, equipment, fertilizers and pesticides. An additional US$30 million was also available through the National Development Plan.

Brunei’s agriculture sector is growing and it recorded US$322 million in revenue in 2018 – a 19 percent increase from 2015. The country currently has 47 percent self-sufficiency in vegetables, 37 percent in fruits and 30 percent in meat, proving that the country has the potential to secure its national food supply.

Increased research in higher yielding varieties and other issues which affect Brunei’s paddy farmers such as soil acidity, fertility, irrigation, and unpredictable weather will ensure the country’s rice industry is on the right track.

Partnerships with existing industry players that are experienced in paddy cultivation, sustained government support, implementation of latest technologies and timely investments from private stakeholders will be just as crucial in helping Brunei meet its self-sufficiency target.

Related articles:

The economics of rice in Southeast Asia