The Rome Statute is a multilateral treaty that helped establish the International Criminal Court (ICC) on 1 July, 2002. The powers of the ICC are limited to prosecuting those who have committed genocide, crimes against humanity, crimes of aggression and war crimes. To date, over 130 countries have signed the treaty while over 100 countries have ratified it. Among the ASEAN countries that have not signed it as yet are Brunei, Indonesia, Myanmar and Malaysia. The Philippines officially left the ICC on 17 March, 2019.

Malaysia originally acceded to the treaty on 4 March, 2019 but has since withdrawn from ratifying it mostly due to fears of losing its sovereignty. In accordance with article 17 of the treaty, signatories will have to accept prosecution and investigation from the ICC if they are unwilling or unable to do so themselves while article 27 and 28 call into question the immunity of those carrying out the atrocities.

Sovereignty

The issue of sovereignty was brought up when the crown prince of the southern state of Johor, Tunku Ismail Sultan Ibrahim, tweeted that the signing could threaten the Conference of Rulers’ sovereignty and in turn, the status of Malays and Islam. While article 13 of the Rome Statute does state that “a situation in which one or more of such crimes appears to have been committed” will allow the ICC to exercise its jurisdiction. However, article 17 states that this would be unnecessary unless a country is “unwilling or unable” to do so.

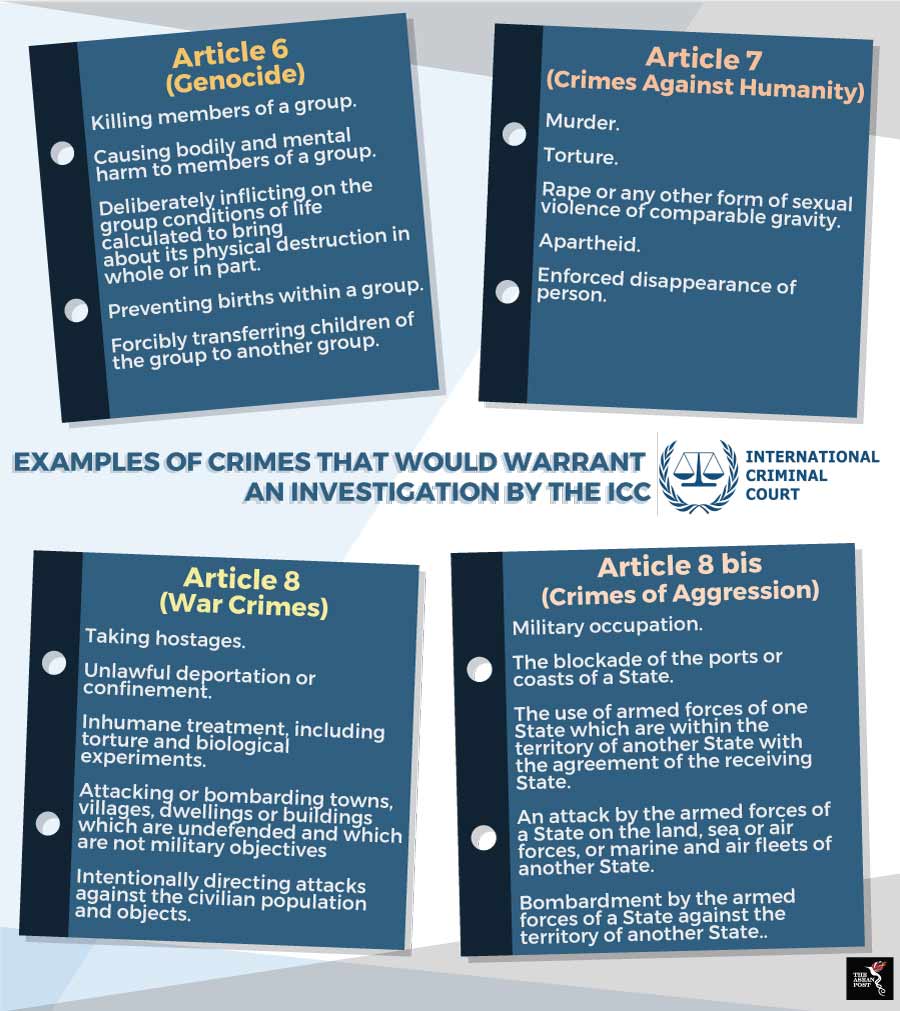

Dr Mahathir Mohamad, Prime Minister of Malaysia, said in a press conference on 5 April, 2019 that the statute only applies to excessive cases according to articles 5, 6, 7, 8 and 8 bis where the statute describes the nature of crimes that warrant an investigation according to article 13. Malaysia’s sovereignty would most likely not be threatened if it signs the treaty, except in the most extreme of cases. For example, if Malaysia turns a blind eye and allows known murderers to roam free without any legal repercussions.

Another issue is the question of immunity. While this valid question was raised by some of Malaysia’s netizens in response to the crown prince’s tweet, it was quickly brushed aside on the grounds that the statute was a threat to the nation’s sovereignty. Articles 27 and 28 of the Rome Statute, in simpler terms, state that in the event of necessity, it shall “apply equally to all persons” regardless of any state-based immunity.

However, by addressing the issue of immunity, Malaysia’s sovereignty and special position of its rulers could be indirectly threatened. According to article 32 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, the King shall not be liable to any civil or criminal proceedings except in the Special Court. The Special Court, formed in 1993 is the court in which, in the event of wrongdoing, the monarchy can be put on trial.

Inconsiderate

One might also argue that the government should have taken into consideration the opinion of Malaysians before signing the treaty. Abdul Rahman Dahlan, former Minister of Urban Wellbeing, Housing and Local Government in a tweet said that “clearly the Foreign Ministry did not do proper engagement of the relevant stakeholders”. This was echoed by a tweet from the crown prince of Johor who said “the Rulers were never consulted”.

By hastily signing the treaty and withdrawing from it within a month, the government’s subsequent U-turn is viewed by many observers in the country as being cowardly or politically motivated.

This debate would not even be happening if Malaysians knew the context in which the ICC could intervene if Malaysia ratifies the treaty. The ICC will only intervene if the judiciary system of a signatory country fails like in the case of the Philippines’ war on drugs or Myanmar’s massacre of the Rohingya - incidentally two nations that are not party to the Rome Statute.

Malaysia can still sign the treaty but only after its people are better informed about the Rome Statute and the role of the ICC. The Conference of Rulers should also be consulted. The Rome Statute does not require a nation to give up its sovereignty but requires strict action in the highly unlikely event of widespread atrocities.

All of this boils down to the confidence Malaysia’s citizens have in their country’s judiciary. Is the current system so inadequate that Malaysia needs the ICC to step in if widespread atrocities occur? Will the immunity of the monarchy enshrined in the Federal Constitution be under threat? Only Malaysians can make that decision and the government of the day should strive to better educate and inform the citizenry before arriving at one.

Related articles:

Can the ICC bring justice to Myanmar?

Pahang sultan is Malaysia’s new king