Better regulations and wider acceptance from the general public are key to the growth of commercial drone use across the region.

Drones are playing an increasingly important role in optimising processes in various industries – providing efficiency and effectiveness while prioritising safety and savings. Their near limitless aerial perspective offers the ability to gather and analyse data, and when combined with artificial intelligence (AI), are revolutionising the way companies inspect, survey and map terrain, infrastructure and agriculture.

Malaysia based Aerodyne has carved a global name for itself by combining drones with AI’s powerful analytics. Apart from asset inspection, management and project monitoring in various sectors, Aerodyne also actively provides services in geospatial intelligence, emergency response, 2D and 3D mapping and precision agriculture.

A relative newcomer to the scene, the four-year-old company now has a presence in 24 countries and is ranked the world’s seventh best drone operator by Drone Industry Insights, a market research and analytics company based in Germany. Kamarul Muhamed, Aerodyne CEO and founder said that the growth in commercial applications for drones has resulted in global interest for his company’s unique AI-driven services. However, he admitted that most of his subsidiaries are based outside of Southeast Asia.

Playing catch-up

Apart from its business in Malaysia, Aerodyne is also active in Indonesia and has contracts in Singapore and Brunei as well. Though he praised the Philippines for being early adopters of the technology, Kamarul said that drones and their accompanying services are tightly regulated in most ASEAN countries.

“In general, ASEAN has adopted a wait-and-see approach to drone use – but we should be taking a leadership role,” Kamarul told The ASEAN Post this week.

“We have inherited a lot of regulations which do not necessarily promote or support (drone) innovation. There are some regulations now based on drones’ usage, their weight and the height they are flown at, but there is no licensing requirement. If we have licensing, we can regulate the industry better,” he stressed.

While Kamarul pointed out that rules are especially tight in countries like Lao PDR and Myanmar, there is no region-wide consensus on drone regulations. Even in Singapore, which has long been at the forefront of technology in ASEAN, lawmakers are still reviewing changes to drone legislature that was proposed by the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS) last April. Among the changes include a pilot licensing scheme, a compulsory online training programme and stricter requirements such as partial or full certification for heavier unmanned aircraft.

Kamarul used BVLOS (Beyond Visual Line of Sight) as an example of legislation playing catch-up with technology. BVLOS is a concept which allows drone operators to gather data over large areas without having to be in close proximity to the drone and is seen as the next step forward for the industry.

“Traditionally, it has been seen as dangerous and irresponsible – but the technology is increasingly maturing. If you certify the operation, it is very safe,” he said.

Market potential

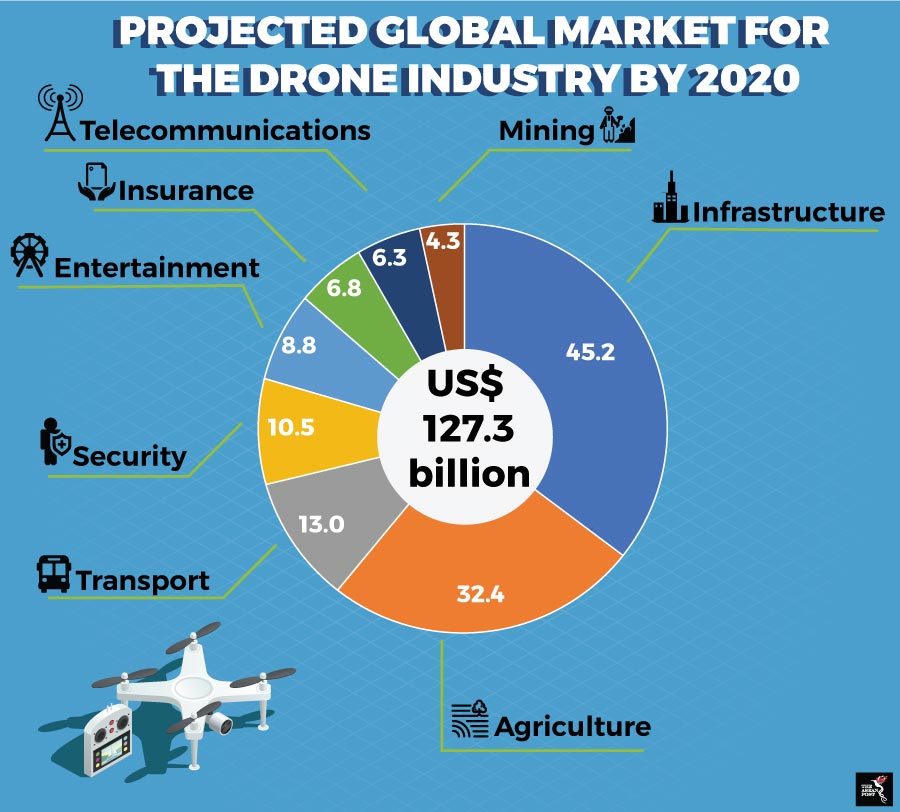

Explaining that while drone adoption is about to go mainstream globally, Kamarul said ASEAN only represents less than three percent of the global drone market which is forecasted to be worth US$127.3 billion in 2020. However, he added that it still represents a substantial sum and there is huge potential within the rapidly growing region. There are a lot of services that can be unlocked in terms of efficiency, and this is especially true in countries which are just building their infrastructure and are looking at cost-efficient ways to maintain them.

Apart from a framework which supports businesses and innovation, there is a need to educate the public on the benefits of drones and their role in building cities of the future. Safety and privacy are the public’s two biggest concerns surrounding drone use, but their increasing adoption in our daily lives is helping to change negative stereotypes.

Airbus successfully trialled the world’s first shore-to-ship delivery in Singapore in March, and in January, Chinese e-commerce platform JD.com conducted what is believed to be Southeast Asia’s first government-approved drone delivery by delivering backpacks and books to Indonesian students in a rural school more than 250 kilometres away. In another regional first, Thailand started using drones to address worker shortages in the farming sector last year, deploying them to help map and survey crops as well as spray fertilisers and pesticides.

While these trials are a good first step, ASEAN member countries should consider implementing training programmes and licencing to better regulate the industry. With drones set to play an increasingly prominent part in the region’s economy, key policies have to be put in place now to ensure better integration without negative effects on society.

Related articles: