In debt, in a foreign country, and probably feeling like they are just in over their heads – many migrant workers in ASEAN will have more important things to think about today while the rest of the world celebrates International Labour Day.

Often low-skilled and undocumented, and nearly always overworked and underpaid, ASEAN’s migrant workers are nevertheless the unsung heroes of the region.

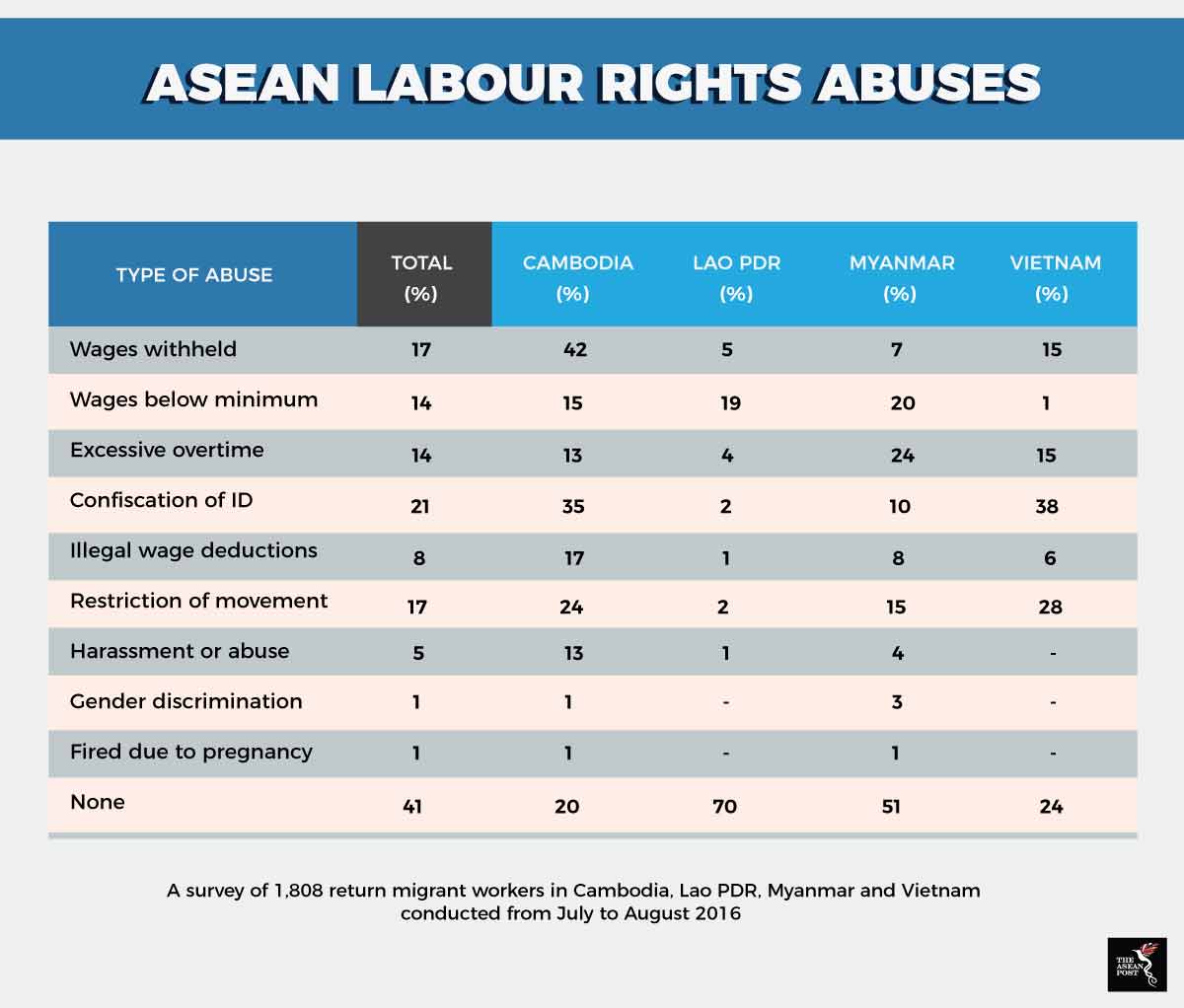

While they play crucial roles in society in everything from building the infrastructure that Southeast Asia relies on to providing the childcare that many parents depend on, the fact is that migrant workers in ASEAN still face numerous prejudices, unsafe working conditions, poor living conditions and lack of access to healthcare.

Migrant workers from countries such as Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Myanmar and the Philippines play a vital role in the agriculture, livestock, seafood, manufacturing, hospitality and other sectors in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Together, these three countries host 96 percent of the total number of migrant workers in ASEAN, or 6.5 million people, according to the World Bank.

Many of these workers have stories of being forced into debt by middlemen who help arrange their permits, documents, travel and accommodation for an exorbitant recruitment fee. And as if that isn’t bad enough already, numerous others find themselves working in different jobs from which they were promised before leaving their home countries.

Lacking the same legal protection and social security net as citizens, they find themselves with no choice but to get on with their jobs. The money they send home is a valuable source of income for the families they left behind to seek better paying jobs abroad.

A World Bank report in 2017 titled ‘Migrating to Opportunity: Overcoming Barriers to Labour Mobility in Southeast Asia’ found that approximately US$62 billion in remittances were sent to ASEAN countries in 2015, and remittances account for 10 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the Philippines, seven percent in Vietnam, five percent in Myanmar and three percent in Cambodia.

All bark, no bite

While the 2007 ASEAN Declaration on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers and the ASEAN Consensus on the Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers signed in 2017 are meant to promote fair treatment of migrant workers, protect their dignity and prevent abuse, exploitation and violence, these issues are still all too common.

Among other things, the 10 ASEAN member countries have agreed to organise pre-departure orientations, simplify processes for overseas placements, prohibit overcharging of recruitment fees, provide fair conditions to work and facilitate access to legal recourse and assistance – although the non-binding nature of the two agreements means it offers plenty of bark but little bite.

Another ASEAN initiative, the ASEAN Economic Community, is aimed at facilitating mobility and easing transitions between jobs. However, these regulations only cover certain skilled professions – doctors, dentists, nurses, engineers, architects, accountants, and tourism professionals – or just five percent of jobs in the region.

There has been little focus on labour rights or social security benefits for migrant workers in ASEAN until recently.

Under pressure to crack down on forced labour, slavery and even murder in its fishery sector, Thailand last month added “forced labour or service” as an offence in its anti-human trafficking law, with a four-year jail term and a US$12,516 fine for anyone found guilty.

In Malaysia, employers who hire foreign workers with valid documents from 1 January 2019 must now register them with the Social Security Organisation (SOCSO) and contribute to the Employment Injury Scheme (EIS) where employees can receive medical, temporary disablement, permanent disablement, dependants’ and rehabilitation benefits, as well as US$1,571 in repatriation costs and funeral expenses.

While ASEAN countries have generally been slow to adopt United Nations (UN) and International Labour Organisation (ILO) instruments that promote migrant workers’ rights, perhaps 2019 – the year the ILO celebrates its 100th anniversary – will see the region clamp down on labour abuses and provide wider access to social security benefits for its often-forgotten migrant workers.

Related articles:

Myanmar migrant workers in debt bondage

Thailand and Malaysia top countries for ASEAN labour migration