Several challenges lie ahead for Malaysia if the former global tin leader is to revive the industry. Speaking to local media last week, Malaysia’s Minister of Water, Land and Natural Resources, Dr Xavier Jayakumar, said the country is looking to restart the industry as prices have now rebounded to US$20,000 per metric tonne.

However, it is not as simple as that.

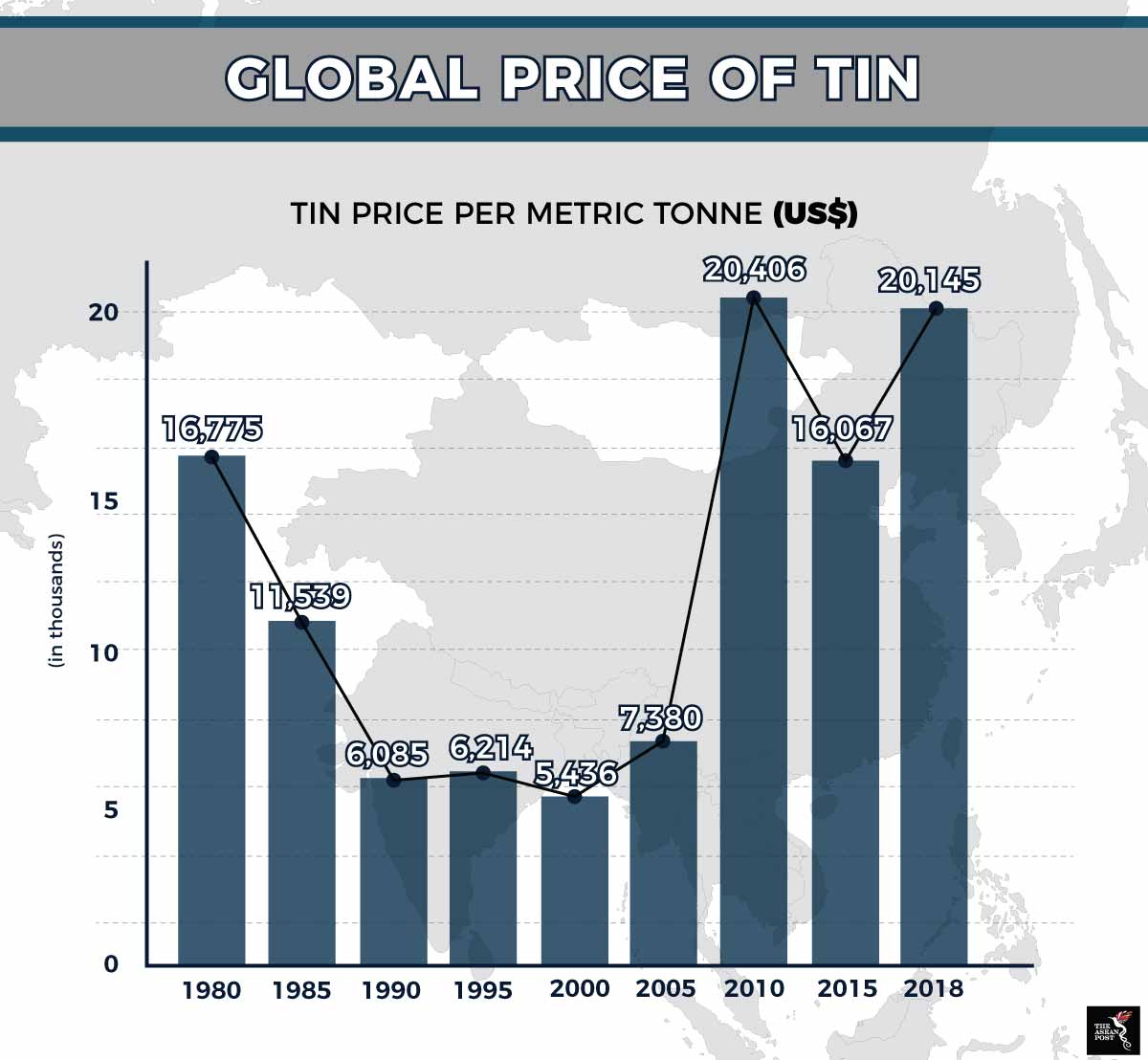

Firstly, prices above US$20,000 are nothing new. World Bank data shows the price of tin has remained at a yearly average of more than US$20,000 per metric tonne in seven of the past nine years (2010 to 2018), so why didn’t the government of Malaysia decide to bring back tin mining earlier?

Tin was first mined in Malaysia in the 1820s and the country became the world’s largest tin producer by the end of the nineteenth century, a position it held until the mid-1980s when it supplied more than half of the world’s tin before prices plunged by 50 percent and ruined the local industry. While the four-decade gap in industrial production may very well mean there are large deposits worth billions of dollars waiting to be mined, there are several factors that need to be considered before any operation begins.

Environment and labour

Mining’s negative impact on the environment is well documented, and proper environmental impact assessments and social impact assessments have to be carried out and verified by independent auditors. Not only does tin mining cause water pollution, it also affects the soil. Malaysia is a land rich in biodiversity and it needs to find a way to mine tin sustainably and not at the cost of environmental degradation; especially with climate change a growing worry.

Water pollution is a huge concern and the Kim River incident in March, when chemicals were illegally dumped in a river in the state of Johor forcing 111 schools in the area to be closed, is still fresh in the minds of most Malaysians. Removing pollutants from the 1.5 kilometre stretch of the Kim River took four days at a cost of US$2.4 million, but not before more than 3,000 people had to be treated for exposure to hazardous fumes.

The labour intensive nature of mining means it will not go down as a popular career choice for most Malaysians, and foreign workers are sure to make up the majority of miners if the sector is to be revived. With the industry long having collapsed in Malaysia, the country also does not have the high-level expertise such as engineers and technicians needed to operate and manage an efficient and sustainable modern-day mine. Foreign talent will inevitably be needed to fill these gaps as well.

Cost and corruption

Mining licenses too have to be granted in a transparent manner. Dr Xavier’s predecessor, Wan Junaidi Tuanku Jaafar, warned of a small circle of industry players getting rich from tin mining at the expense of the government and the environment adding that there was a lack of information on the quality and quantity of tin reserves.

Even initial exploration involves high capital investment, and in a country like Malaysia which has among the most exhaustively mined sites, finding cost-effective mines will be key. Just as important will be the long term trend of prices, which has to be analysed thoroughly to ensure another slump will not kill the industry off for good.

While the metal has long been used in industries such as electronics, automotive and food and beverage packaging, it is now also growing in importance in the renewable energy sector as a component in solar panels as well as in electric vehicles and robotics. The International Tin Association in a market analysis on 16 April stated that with tin supply slowing due to long-term declines in mine grades, new sources of tin need to be found; something Malaysia could capitalise on. But with production from the world’s largest tin producers, Indonesia and China, likely to remain stable in the short-term, it remains to be seen how profitable tin mining will be for Malaysia.

Related articles: