Towards the end of last month, on 21 June, the government of Myanmar ordered mobile phone operators in the country to shut down all Internet data across at least eight townships in Rakhine and one in neighbouring Chin state. The United States (US) has since urged an immediate end to the blackout, saying that a service restoration would help provide transparency to what the government of Myanmar says are law enforcement actions to avert civil unrest.

About a week after Myanmar’s mobile blackout, on 27 June over in neighbouring Thailand, reports revealed that the Defence Ministry and armed forces there had been told by Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Prawit Wongsuwon to take legal action to curb the spread of so-called "fake news" and information online.

Meanwhile, a Cambodian court jailed a fixer and translator for two years for his role in making a documentary about sex trafficking in the country which the government said contained “fake news”. Critics, however, have often accused Prime Minister Hun Sen as having launched a crackdown on government critics, including human rights advocates and opposition politicians, adding that he has in recent years used the term “fake news” to discredit dissenting voices.

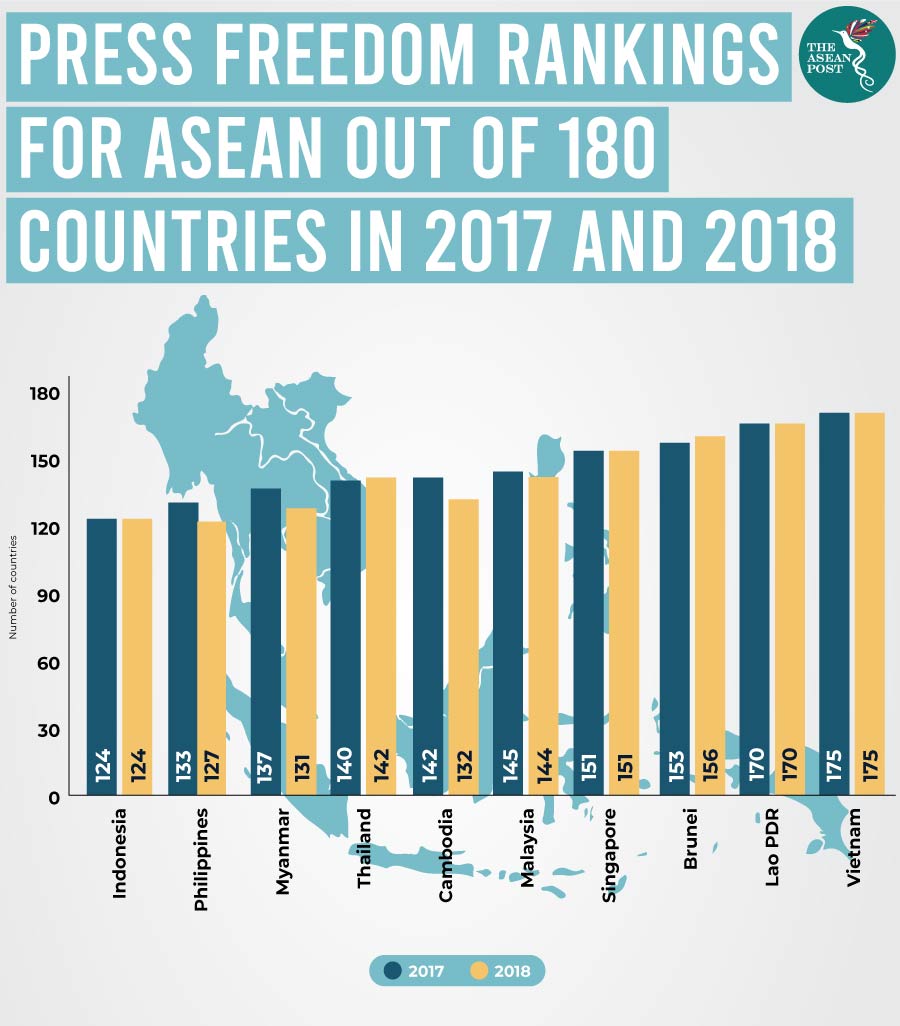

It is no secret that the term “fake news” has become a buzzword since Donald Trump was voted in as US President and has often been thrown about by leaders wanting to shut down critics. It is also no secret that most of ASEAN has never ranked very well when it comes to media freedom. While certain member states have made progress, the scores (according to several sources) have never really been celebratory.

And so, whenever the term “fake news” is thrown about by governments – especially those in Southeast Asia – it is often looked at with a certain degree of scepticism. The question often asked is whether the news is indeed “fake” or whether the government in question is attempting to shut down dissent.

Unfortunately, recent cases in the region have not provided sceptics with much confidence in the former notion either.

Case studies

In Myanmar, the case involving Reuters journalists, Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo has already become infamous, both in the region and most of the world. The two journalists were arrested in December 2017 for allegedly accepting secret documents from the police in connection to a story they were working on.

According to facts of the case, prior to the arrests, the two journalists were working on a story about 10 Rohingya Muslim men and boys who were killed in western Myanmar’s Rakhine state.

The testimony by Police Captain Moe Yan Naing revealed that a superior had arranged for two policemen to entrap Wa Lone by offering him “secret documents” and then arresting him. This contradicts the prosecution’s story that Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo were arrested at a routine traffic stop and found to be in possession of secret documents.

Months ago, in the Philippines, prominent journalist and Rappler CEO Maria Ressa was arrested on cyber libel security charges for an article published in 2012. The article in question centres around alleged links between Supreme Court Justice Renato Corona and wealthy businessmen around the time of his impeachment.

The National Bureau of Investigation last year concluded it had grounds to file a criminal complaint around the libel claim. This was despite the fact that the law used to prosecute Rappler and Ressa was passed months after the story was published.

Rappler is also known for being critical of current Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his administration, and the president has publicly clashed with Rappler regularly. He has accused it of being funded by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and regularly refers to its reporting as “fake news,” while Ressa has often spoken out against the president in international circles. In a 2016 Bloomberg interview, she detailed how the Duterte administration had turned Facebook into a “weapon” and utilised “patriotic trolling” to silence critics online.

The problem

Fake news is no joke. It is real and it is dangerous as can be seen in the example of numerous lynching incidents in India where people have been killed thanks to the spread of fake news through popular messaging app, WhatsApp. WhatsApp itself has taken several steps in order to combat the use of its app to spread fake news including a tag that appears indicating when a message is forwarded.

Unfortunately, as leaders of governments have learned that fake news exists and the real dangers associated with it, many of them may have resorted to using the term to silence criticism aimed at their administrations.

The fear here is that as the term “fake news” is abused, scepticism about its existence and related dangers will also grow. Many already know that in the ending to the famous fable “The Boy Who Cried Wolf”, the boy’s sheep are slaughtered when the wolf finally does come. That truly is a scary thought and one that governments should keep in mind the next time they think about using the term “fake news”.

Related articles: