Some Cambodians are blaming domestic abuse on the victims. At least this is what the findings from several studies suggested, including a recent joint study conducted by three NGOs (Non-governmental organisations) – Klahaan, Urban Poor Women Development, and People in Need. These NGOs released their findings in a report entitled “Experiences of Gender-Based Violence in Urban Poor Rental Housing Communities of Phnom Penh”.

The survey was carried out between December last year and February in three selected districts in the Cambodian capital - Russey Keo, Mean Chey and Donkor – using 167 households, six focus group discussions and 20 key “informants” which included village chiefs, police and community leaders.

The survey found that while the perception from the majority of respondents was that gender-based and domestic violence was decreasing, the culture of “victim-blaming” still persisted.

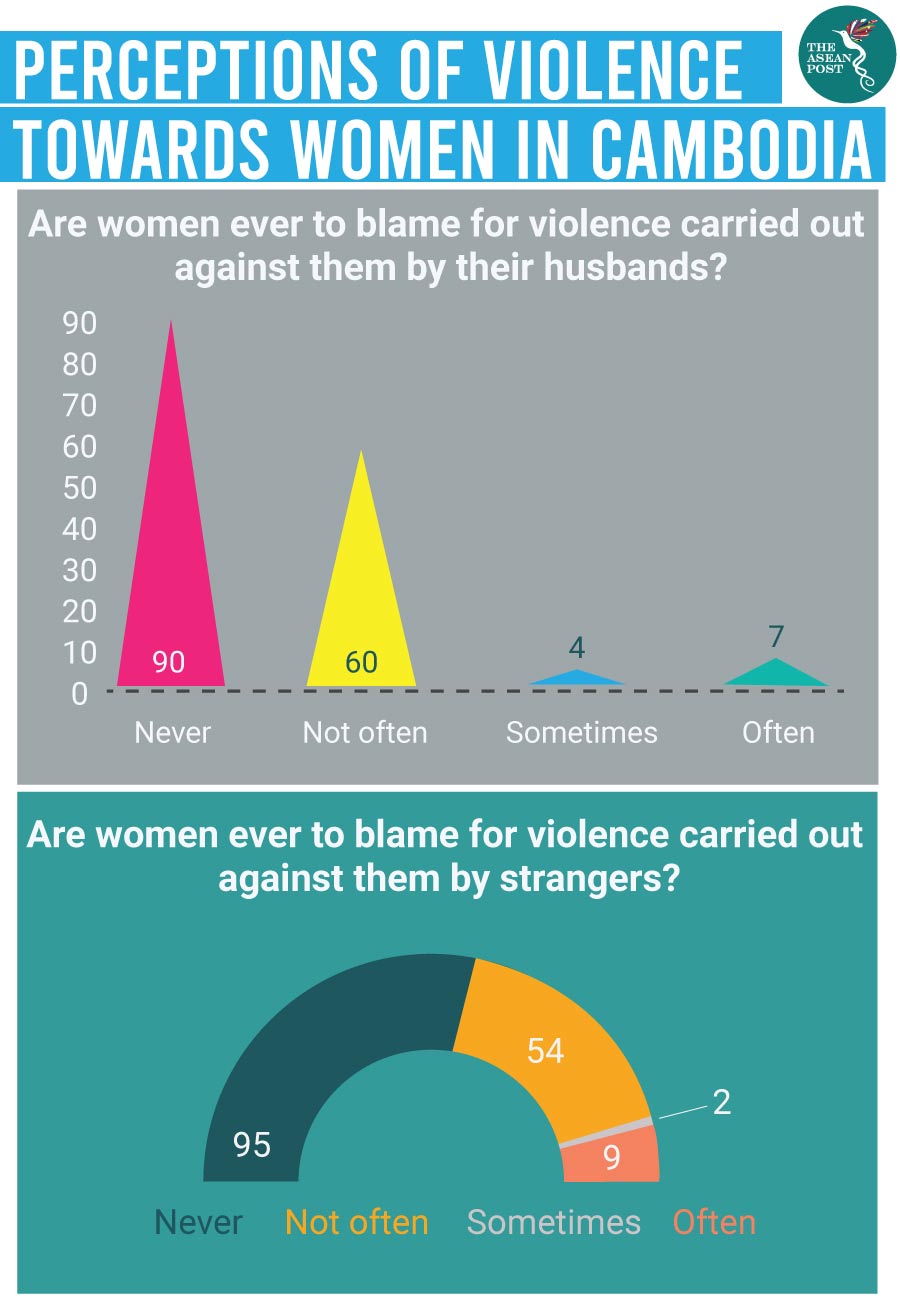

In the quantitative (household survey) data, almost half of respondents felt that women were at least sometimes to blame for violence committed against them by their husbands.

“The findings show that women who experience violence still face a significant degree of blame apportioned to them by some members of the community, including by some community leaders and duty bearers,” the report noted.

But the numbers from the household do not nearly paint as dreary a picture as the responses gathered from key informants. Two different police officers felt that the woman was to blame if “the woman was gambling”, or “the woman was walking alone at night.”

As if these answers from those meant to protect and serve weren’t depressing enough, some women even felt that their own gender was to blame at times. “For example, when women don’t do housework.” said one female resident.

Even women community leaders felt there were times when the women were to blame: “Sometimes it is because of the way women dress (too sexy, or revealing),” said one. “Some women did not know their roles, for example cooking or taking care of children,” said another. “Sometimes mothers did not take care of their daughters well, and their daughters have become rape victims,” said yet another.

Chbab Srey

Chbab Srey is a poem that was orally passed down from the 14th to 19th centuries, and then codified in written form. The poem details a mother’s advice to her recently married daughter. As narrator, the mother advises her daughter to maintain peace within the home, walk and talk softly, and obey and respect her husband.

The poem survived recent Cambodian history, which saw the complete destruction of the Cambodian education system at the hands of the Communist Party of Kampuchea, or Khmer Rouge, and mass genocide that targeted teachers, monks and those considered part of the educated elite.

Emily Anderson from Florida International University, and Kelly Grace from Lehigh University note that the persistence of Chbab Srey in Khmer culture, despite the Khmer Rouge’s attempts to wipe out Khmer culture through mass genocide and banning of Khmer cultural expression; the inclusion of Chbab Srey in the newly rebuilt education system and curriculum are indications of the poem’s importance in Cambodian society.

According to the Cambodian Committee of Women (CAMBOW) in a report published way back in 2007, entitled “Violence Against Women: How Cambodian Laws Discriminate Against Women”, the problem of discrimination against women in Cambodia is rooted in tradition and that this, in part, is thanks to the Chbab Srey.

“In Cambodia, women have traditionally been seen as being inferior to their male counterparts. This is reflected in traditional codes of conduct such as the Chbab Srey (Women’s Law) that teach women to be subservient to men.

Klahaan, Urban Poor Women Development, and People in Need believe that in order to address the issue of gender-based violence (GBV), an attitudinal and behaviour change is essential.

“Research shows that despite how 'safe' the urban environment is rendered via improved infrastructure, if domestic violence is seen as ‘normal’ and men feel a continued sense of entitlement over women’s bodies – for example in public spaces at night time – then GBV will continue to occur. All GBV programmes should include specific attitudinal change objectives, with education and strong messaging on women’s sexual autonomy and bodily integrity.”

Related articles: