While a recent report by two civil society groups in Cambodia outlining predatory practices by local microfinance institutions (MFIs) may not paint the clearest picture of the sector, there is no denying that there are murky waters ahead.

The report by the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) and local NGO Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) documented numerous cases of coerced land sales, child labour, debt-driven migration, food insecurity and other human rights abuses during interviews of 28 households that were unable to repay their debt.

“Each of these individual issues raises serious concerns (and) they are likely to become more routine and widespread as the levels of debt in Cambodia continue to grow,” stated the report titled ‘Collateral Damage: Land loss and abuses in Cambodia’s microfinance sector’.

Although the researchers stressed the report was not intended to be statistically representative of Cambodia, or of MFIs’ 2.4 million clients in the country, it showed that land loss and other human rights issues resulting from unpaid loans could lead to rising inequality and social unrest.

Worrying numbers

Those 2.4 million Cambodians hold a total of at least US$8 billion in outstanding microloans, an amount equal to about one-third of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) for 2018, stated the report.

However, the US$8 billion figure is a conservative estimate as it only captures MFIs and two commercial banks. There were more than 80 MFIs registered with the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC) at the start of 2019 – and there are additional hundreds of smaller NGOs, rural credit operators and unlicensed moneylenders that also offer microloans.

The average microloan debt per borrower in Cambodia is around US$3,370 – the highest average amount in the world according to the report. That amount is close to the entire median disposable income for rural Cambodian households in 2017 (about US$3,900) and more than double the 2018 GDP per capita (US$1,512).

Although the World Bank has stated that Cambodia’s share of non-performing loans in its microfinance sector stood at two percent as of late 2017 – which is low by international standards – how much of this can be attributed to the coerced land sales as described in the report is not known.

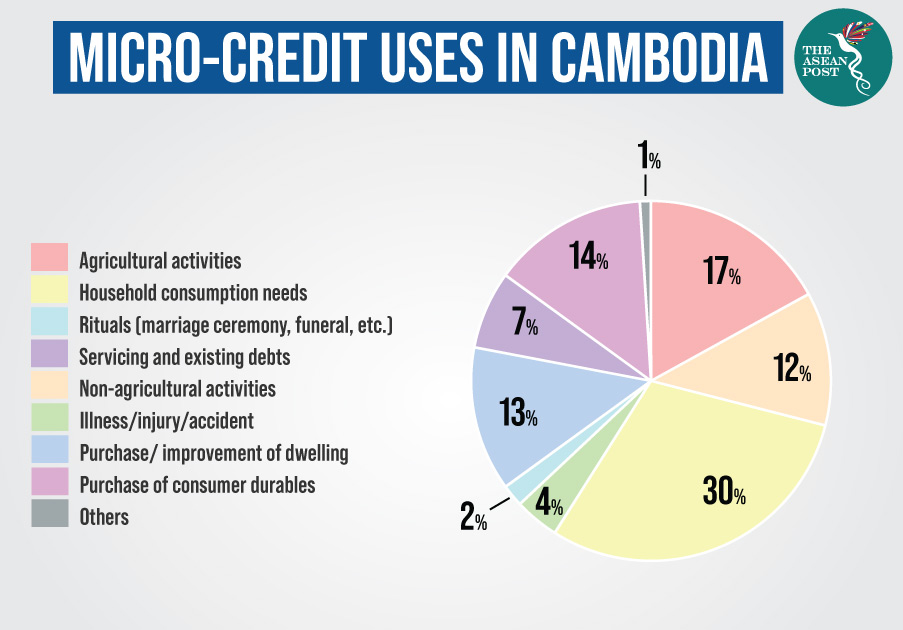

While many borrowers took out loans to set up small businesses or to pay for necessities such as food and medicine, a sizable portion was used for household items or consumer goods such as motorcycles or mobile phones. Loans were also used for agricultural purposes such as buying machinery or farm animals, and for those whose ability to repay their debt depended on how well their farms did, low prices or droughts inevitably led to an inability to service their debt.

CMA to investigate

The Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA) has been quick to refute the report, stating in a press release that the case study based solely on negative outcomes of MFI borrowing “does not reflect the true MFI lending that has benefitted hundreds of thousands of Cambodians”.

“The CMA takes very seriously any reports of unethical or predatory lending practices and we will work with our members to investigate the case studies presented in the report,” said the CMA.

The CMA also disagreed with the report’s comparison of average loan size to GDP per capita as it claimed the figure included loans made to small and medium enterprises and not to individuals.

Noting that microfinance has been an integral part of Cambodia’s economic growth and has contributed to a reduction in poverty levels from 47 percent in 2007 to 13.5 percent in 2014 according to the World Bank, the CMA claims that the Cambodian microfinance sector has proven to be “one of the most successful models for financial inclusion worldwide”.

While that may or may not be true, microfinance lenders charged interest rates of up to 43 percent prior to the introduction of an interest rate cap in April 2017 – which limited interest rates to 18 percent. And as the Microfinance Index of Market Outreach and Saturation (MIMOSA) notes, from 2003 to 2014, loan sizes in Cambodia grew four times faster than borrowers’ incomes.

Key issues

Microfinance in Cambodia began in the early 1990s as the country looked to rebuild after years of instability during the Khmer Rouge’s rule. Foreign aid donors and international development agencies helped provide poor Cambodians with access to credit, and the sector exploded in 2009 with an influx of foreign investment that has seen rapid growth which continues until today.

Although the World Bank pointed out that growth in microcredit has had positive financial and welfare impact on households in Cambodia, allowing the share of households that borrowed from formal sources of credit to quadruple from 2004 to 2016, they also note that risks are increasing for MFIs and for the Cambodian economy in general, partly reflecting looser lending practices.

In a report titled ‘Microfinance and Household Welfare: Cambodia Policy Note’ released in February, the World Bank stated that the average loan size in Cambodia has increased more than tenfold over the past five years – as has the share of loans. These trends are due to a combination of the low penetration of financial instruments, deteriorating lending practices and low financial literacy rates.

While MFIs in Cambodia are set to remain a feature of the credit landscape for the foreseeable future, improving transparency, lending practices and supervision to reduce risks are issues that all relevant stakeholders should work towards in order to ensure the sector’s long-term sustainability.

Related articles:

Alleviating poverty with microfinancing