Thailand could be the next major ASEAN city to move its capital. Speaking at a seminar titled ‘Connecting Thailand with the World’ on Wednesday, Thai Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha brought up the possibility of moving the country’s capital, Bangkok – potentially following in the footsteps of Indonesia, which last month confirmed it will move its capital away from the congested and sinking Jakarta to the rainforests of Borneo.

Prayut noted there were two possible approaches to moving the crowded Thai capital.

“The first is finding a city that’s neither too far nor too expensive to move to. The second is to decentralise the urban area to outer Bangkok to reduce crowding,” he said.

“Past governments were never able to pull this off, fearing it would cause irreparable conflict in society,” Prayut added.

The Thaksin Shinawatra administration (2001 to 2006) studied a possible move to Nakhon Nayok, a province about 100 kilometres north-east of Bangkok, and there were also studies two years ago about the possibility of moving government offices to Chachoengsao, a province about 80 kilometres east of Bangkok.

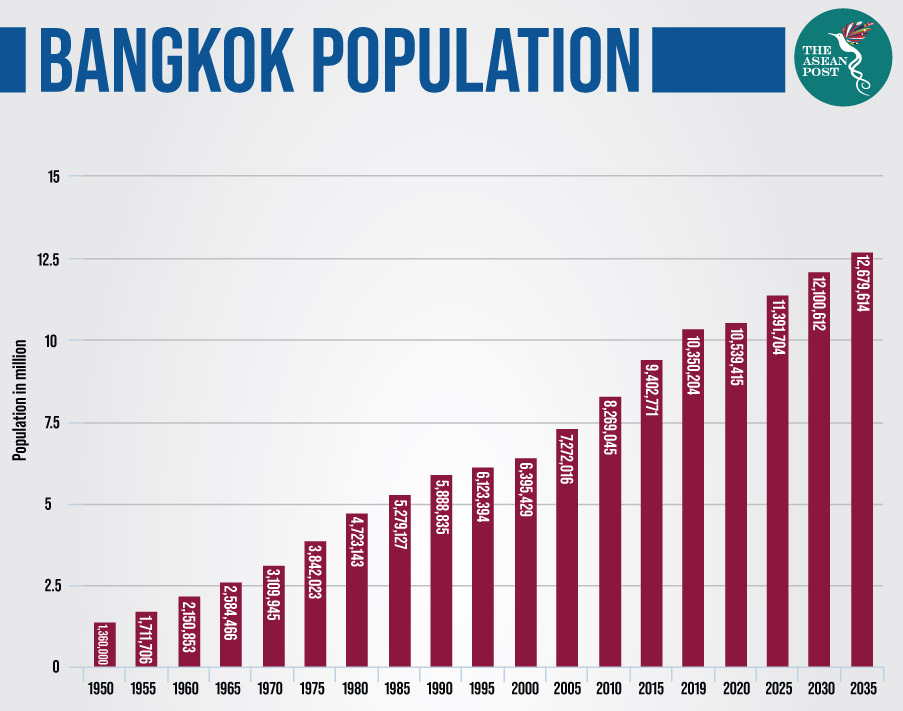

As with Jakarta, Bangkok also faces challenges such as rapid population expansion – both are cities of more than 10 million people – and climate change concerns such as pollution, land subsidence and rising sea levels.

Bangkok was named the world’s eighth most congested city in the world by a global traffic index last year, and an especially bad spell of smog at the beginning of the year caused health scares and school closures.

Built on once-marshy land, Bangkok is projected to be one of the cities hardest hit by climate change along with Jakarta and Manila, and the World Bank estimates that nearly 40 percent of Bangkok will be inundated in 2030 due to extreme rainfall and changes in weather patterns.

The 2011 floods were Thailand’s worst in 70 years and came at an economic cost of US$46 billion to the country. Around US$8 billion was spent on restoring Bangkok alone, where the floods affected at least 9,859 factories and 660,000 jobs. Moving forward, the World Bank predicts that almost 70 percent of the increase in flooding costs in 2050 for Bangkok will be due to land subsidence.

Still building

Despite these and other threats, Bangkok has not stopped building.

A major tourist destination, Bangkok has plans to extend the Suvarnabhumi Airport – Thailand’s main international gateway – and the city’s subway system.

Opened in 2006 with a yearly capacity of 45 million passengers, the Suvarnabhumi Airport is now handling 65 million visitors and Thailand has announced a US$7.9 billion programme to expand the airport and increase annual capacity to 150 million passengers by 2030.

The metro line across Greater Bangkok will be 464 kilometres long by 2023, which will surpass those of London (402km) and New York City (380km) according to Bill Barnett, managing director of the C9 Hotelworks consultancy which organised the ‘Megacity Bangkok – A Tourism and Hotel Futurescape’ forum in Bangkok last year.

“This new accessibility … is going to transform Bangkok into [an] Asian ‘megacity’, a huge city on a global scale the likes of which can only be seen elsewhere in the region in Shanghai and Tokyo,” he said.

As industry experts at last year’s Thailand Tourism Forum agreed, the subway system will open up more space for households and businesses, and with it more opportunities for the travel and tourism sector.

A Mastercard report released earlier this month saw Bangkok retain its top spot on a list of Asia Pacific’s most popular destinations for international travellers with 22.8 million overnight international arrivals last year, holding on to the title for the fourth straight year.

Thailand’s biggest shopping mall, the US$1.8 billion IconSiam, opened to huge fanfare last November and helped cement Bangkok’s reputation as a shopping haven.

Solving problems

Instead of risking these and other investments, solving Bangkok’s numerous problems might be a better solution than packing up and relocating.

Prayut’s second option, decentralising government offices and businesses to Bangkok’s perimeter, will reduce congestion as less people would have to travel to and from the city’s centre.

Improving connectivity between the different train lines so commuters can easily transfer from one line to another, and integrating water-based transport networks with road and rail systems, will encourage a shift to public transport and lessen congestion woes.

Investing in a more climate resilient Bangkok by strengthening flood management systems, better regulating land use as well as building stronger and safer infrastructure will help mitigate the effects of climate change in the city.

While moving the capital is just an idea at this stage, more research needs to be done regarding the economic, social and environmental impacts of relocating one of ASEAN’s most vibrant hubs.

Related articles:

New “Jakarta” may cause environment crisis