In September last year, Cisco and Oxford Economics analysed 433 occupations across 21 industries. Looking at the ASEAN-6 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), the study revealed that, in Indonesia, about eight percent of the workforce (9.5 million people) would probably lose their jobs due to automation and job displacement.

This month, McKinsey and Company published a report titled “Automation and the future of work in Indonesia.” In that report, McKinsey noted that in Indonesia – along with the rest of the world – there is little doubt that especially repetitive work, such as data collection, will indeed be increasingly automated. However, as with technological innovation in previous eras, new work will also be created, and many jobs will change.

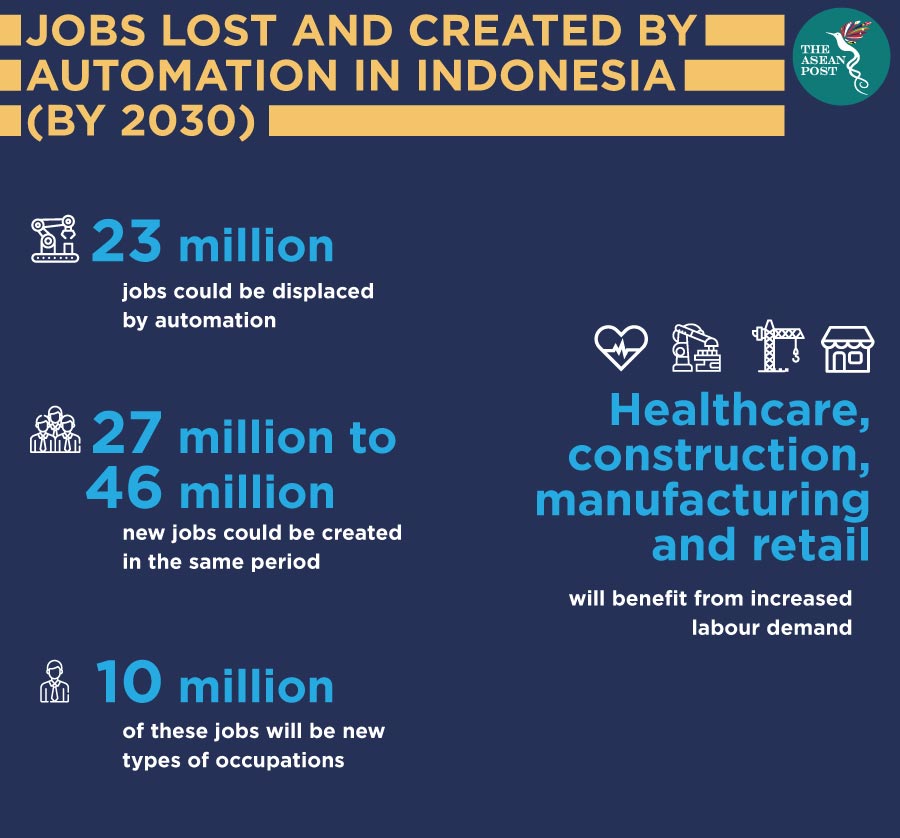

“Overall, our research indicates that the jobs story can be a positive one in Indonesia. Even with the adoption of automation and the accompanying potential displacement of some jobs, we find that the number of net new ones created (in other words, the difference between jobs gained and jobs lost to automation) could range from four million to 23 million by 2030,” McKinsey says.

Nevertheless, there is a catch if Indonesians want to make the most of these new jobs. Cisco and Oxford Economics, and McKinsey have mentioned the need to address skills transitions. Both agree that in this, a concerted effort from all stakeholders is needed.

Reports in early October last year revealed a lack of high-skilled talent in the country. In an interview, Tom Lembong, the nation’s investment board chief provided some interesting insights into the challenges of creating high-skilled talent when he spoke of a conversation he had with a local partner to a Chinese company that has invested US$5 billion in an industrial park in Central Sulawesi.

“The local partner told us they posted jobs for 500 positions. Nine people signed up," he said.

In fact, as far back as 2016, the problem of a high-skilled labour shortage had been highlighted in a report which quoted educationists, economists and business leaders. Eko Prasetyo, director of the Education Fund Management Institution, an arm of the Indonesian Ministry of Finance, said then that the problem was quality skills and productivity.

“We have to produce more engineers. We have to produce more researchers. We can’t just be an economy led by natural resources,” he enthused.

According to the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, out of Indonesia’s six million university and postgraduate students, 20 percent are majoring in Islamic studies and more often than not, these graduates won’t find work in their chosen field of study.

The right direction

There is still good news, as far as Indonesia is concerned.

“Under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, the government is determined to transform Indonesia into an Industry 4.0 economy and has chosen the 10 national priorities of an integrated road map. Recently, it launched multiple initiatives, including some that involve skill building, to increase the pace of adoption by companies,” McKinsey stated in its report.

In July, Mohamad Nasir, Indonesia’s Minister of Research and Higher Education was reported as having urged all higher education institutions, particularly state universities, to produce competent undergraduates and diploma graduates in line with industry demands.

“This is an effort to improve the quality of human resources. Hence, universities can no longer afford to produce graduates that are unable to meet the requirements of the industry," he said after attending the Plenary Meeting of the Indonesian Economic Scholars Association (ISEI) at Stikubank University, Semarang,

Private companies are on board in helping Indonesia as well. In October last year, Alibaba Group co-founder Jack Ma revealed that he was in discussion with the Indonesian government regarding the possibility of opening an institute to train tech entrepreneurs in the country. This, he said, would help Indonesia meet the skill demands of Industry 4.0, also known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Speaking on the side-lines of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank meetings in Bali, Ma, who is also an adviser to the Indonesian government for e-commerce, revealed that Alibaba was also planning to train hundreds of developers and engineers on cloud computing to help make Indonesian businesses more digital-savvy.

By all accounts, Indonesia seems to be moving in the right direction, however the issue of a lack of high-skilled talent still persists today. As McKinsey has advised, all stakeholders must do their part to ensure that all Indonesians have a brighter future ahead of them.

Related articles: