Vietnam’s Ministry of Public Security recently proposed significantly higher fines for sexual harassment and molestation. A draft amendment to a government decree on social evils and public safety violations says people who sexually harass, molest others or perform sexual acts in public could be fined between VND3 to VND5 million (US$129 to US$215). The current maximum fine for these violations is just VND300,000 (US$13).

For a long time now, both law experts and the public have been discussing numerous legal loopholes in the country which allow sexual offenders to get away with a slap on the wrist. In March, a man was fined just VND200,000 (US$9) after forcibly kissing a woman in an elevator in Hanoi. Earlier in September, a man who groped a woman in central Quang Nam Province while she was drying clothes on the street also got away with a meagre VND200,000 fine.

Sexual harassment is widely prevalent in Vietnam, with several studies showing that Vietnamese women are generally unsafe from the phenomenon. But it’s not just grown women who are being sexually abused.

A 2014 report by Action Aid, an international non-governmental organisation (NGO), found that 87 percent of interviewed women and girls had faced sexual harassment in public places. More recently, Vietnamese police recorded 1,547 child abuse cases in 2018 but due to the culture of secrecy around abuse, the real numbers are suspected to be much higher. Rana Flowers, United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) Representative in Vietnam, was quoted as saying that the figures were likely to be the “tip of the iceberg”.

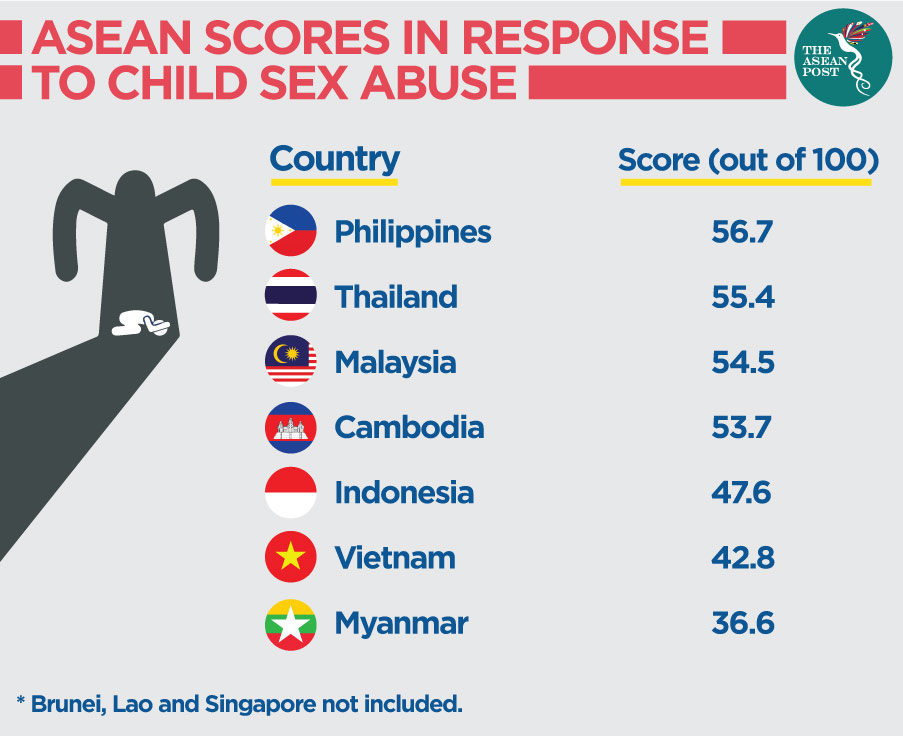

Early this year, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) released a report in which it placed Vietnam 37th out of 40 countries in terms of its response to child sex abuse. Vietnam also scored significantly lower than other ASEAN countries included in the index – the Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia, Cambodia, Indonesia.

Later, in an updated version of the report including 60 countries, Myanmar scored the lowest. Vietnam, however, fell even further to 43rd place.

Better laws

Vietnamese lawyer Truong Anh Tu recently told local media that while the Ministry of Public Security’s proposal for more stringent punishments was all well and good, the ministry must also properly define what constitutes harassment, molestation or public sexual acts to apply these fines effectively, adding that there was currently no document that does so.

Similarly, Dang Van Cuong of the Hanoi Bar Association told Vietnamese media that part of the problem may lie in the country’s law that currently lacks effective sanctions against sexual harassment. He was quoted as saying that the 2015 Criminal Code addresses the act of rape but has no specific provisions for sexual harassment.

As for children, however, the EIU noted that Vietnam’s Penal Code contains provisions that specifically cover the sexual abuse and exploitation of children. The government maintains records on the number of sexual abuse offences against children, and there are guidelines for trials involving such offences.

In June, UNICEF noted that Vietnam had made considerable progress in strengthening national laws to address violence against minors. The Law on Children 2016, Penal Code 2015 and Criminal Procedure Code 2015 include many important new provisions to better protect minors from sexual abuse and other forms of violence.

Nevertheless, UNICEF also noted that there are some remaining gaps that need to be addressed to further align national laws with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution and Child Pornography (OPSC), both of which Vietnam has ratified.

The key reforms UNICEF urged the government of Vietnam to undergo as far as legislation goes to protect children are: to clarify the definition of “sexual intercourse” and “other sexual activities”, to penalise all forms of sexual abuse, contact and non-contact, of children, to reinforce and clarify the age of consent for sexual acts, to penalise people who use their position of trust or authority to sexually abuse a minor, to clarify what constitutes using a child and a minor for pornographic purposes, to prohibit grooming or luring of children and minors, to penalise child pornography in line with the OPSC, to align the definition of child prostitution to the OPSC, as well as to ensure protection and support for all child sex abuse victims under 18 years old.

It seems that as far as protecting Vietnam’s women and children go, a common theme is the need for more clearly defined laws.

Related articles: