Singapore’s decision to ban advertisements of certain fizzy drinks and juices might be just what it needs to change the public’s perception of sugar.

The country has one of the highest rates of diabetes in the world, and Thursday’s announcement came after an eight-week public survey earlier in the year on how best to reduce Singaporeans’ sugar intake from sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs).

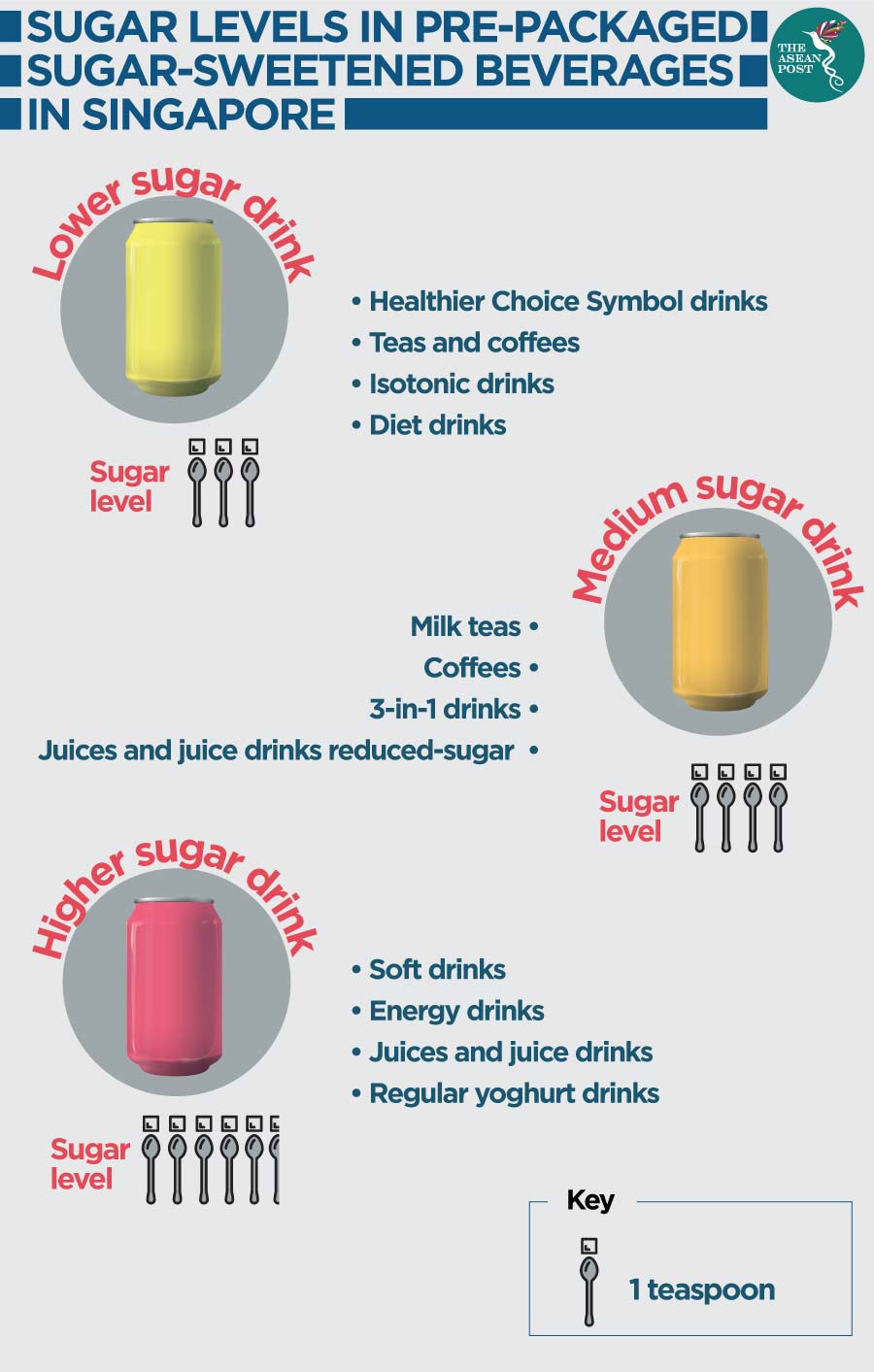

Singapore is among Asia’s biggest per capita consumers of sugar at an average of 12 teaspoons (or 60 grams) of sugar daily – double the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendation. More than half of Singaporeans’ daily sugar intake come from SSBs, of which pre-packaged SSBs contribute 64 percent.

“This is a concern because on average, an additional 250 millilitres (ml) serving of SSB per day would increase the risk of diabetes by up to 26 percent,” said Edwin Tong, Singapore’s Health Minister. “This is not a small number.”

Among the other proposals Tong outlined on Thursday include requirements for certain high-sugar drinks to bear "unhealthy" packaging labels. The minister said Singapore was also considering the introduction of an excise duty or a tax on manufacturers and importers, as well as an outright ban on sale of high-sugar SSBs.

Local media reported that the timing and scope of the new measures is set to be announced next year while implementation is expected to take one to four years.

As addictive as cocaine

While sugar’s link to diabetes, obesity and a variety of ailments that stem from them is well documented, “sugar addiction” seems to be an issue which the public is not ready to face up to.

Like alcohol and tobacco, sugar is a mood-altering substance which can be used for both, reward and pleasure.

However, the general public would be hard pressed to compare sugar with alcohol and tobacco – especially the latter, which is now seen as socially unacceptable.

A 2016 review in the British Journal of Sports Medicine compared sugar addiction to that of cocaine or opium, and although it was criticised by certain quarters, sugar has been scientifically proven to activate dopamine – the neurotransmitter in our brains that is responsible for motivation and reward.

“Sugar activates the opiate receptors in our brain and affects the reward centre, which leads to compulsive behaviour despite the negative consequences like weight gain, headaches, hormone imbalances and more,” said registered nutritionist and dietitian Cassie Bjork in an interview with American health information website, Healthline.

Therein lies the problem.

Despite its potential for psychological dependence, the sale of sugar is unregulated, unlike alcohol and tobacco.

While society may have its reservations about alcohol and tobacco, this same stigma does not apply to sugar, and the abundance of specialty shops which sell ice-cream, donuts and other confectionary is testament to this.

In addition, different types of sugars are commonly added to food and drinks nowadays – making it an almost inescapable part of our diets.

Sweets and other sugary products are easily available to children and corner shops often sell them for a few cents.

While SSBs with more than three teaspoons of sugar per 250ml serving are not allowed to be sold in schools in Singapore, there is nothing stopping students – and the general population – from satisfying their sweet tooth at other avenues.

Children crave sugar and supermarkets are wise to this, prominently displaying sweets and chocolates at checkout aisles and near entrances in a calculated attempt to get children’s attention – a marketing ploy the United Kingdom (UK) has recently clamped down on.

Alcohol and tobacco advertising in Singapore

Children are especially vulnerable to advertising, and while there is no blanket ban on online alcohol advertising in Singapore according to lawyer Denise Mirandah, the advertisement of alcohol in television is not allowed to be shown during programmes intended for children and young persons.

Advertisers must also ensure that their advertisements do not emphasise the stimulant, sedative, or tranquilising effects of any drink and encourage over-indulgence and excessive consumption.

Singapore has banned virtually all advertising of tobacco products in its bid to systematically paint tobacco use as a socially unacceptable and undesirable activity – with point of sale product display prohibited at retail outlets.

Starting from next July, tobacco products sold in Singapore must have standardised packaging and enlarged graphic health warnings – and the packaging of tobacco products will not be allowed to show logos, colours, images or other promotional information associated with the tobacco brand.

However, judging how effective these regulations have been is debatable.

Even if advertising bans do not directly reduce consumption of SSBs and other sweet products in Singapore, they can hopefully still help shift public opinion on one of society's most underrated addictions.

Related articles:

Greying Singapore embraces technology to face health challenges