Picture this: You spend years studying for a degree. After graduating, naturally, you start looking for a job so you can be your own person and not have to rely on your parents anymore. There aren’t many jobs available at the moment but you apply for the ones that are and that suit you – a graduate – and your newly acquired qualifications. Months pass and you still find yourself unemployed, not earning a salary. Eventually, you start to worry.

What does the government and private sector ask you to do? To consider low-end jobs. Jobs that do not match the degree you spent so long trying to obtain. Jobs which companies are currently hiring foreigners for because these foreigners are willing to do the job and work long hours at such low pay because of the economic strife they currently face back home.

After years studying for that certificate you now hold in your hands, after recalling the promises your parents and teachers made - that you will go far if you study hard - would you consider this option? Odds are, even if you did, you would not be too happy about it.

Earlier this week, local Malaysian media quoted the Malaysian Employers Federation (MEF) as saying that there were more than enough jobs in the market. However, Malaysians were not willing to take up these low-end jobs which made up the brunt of those available.

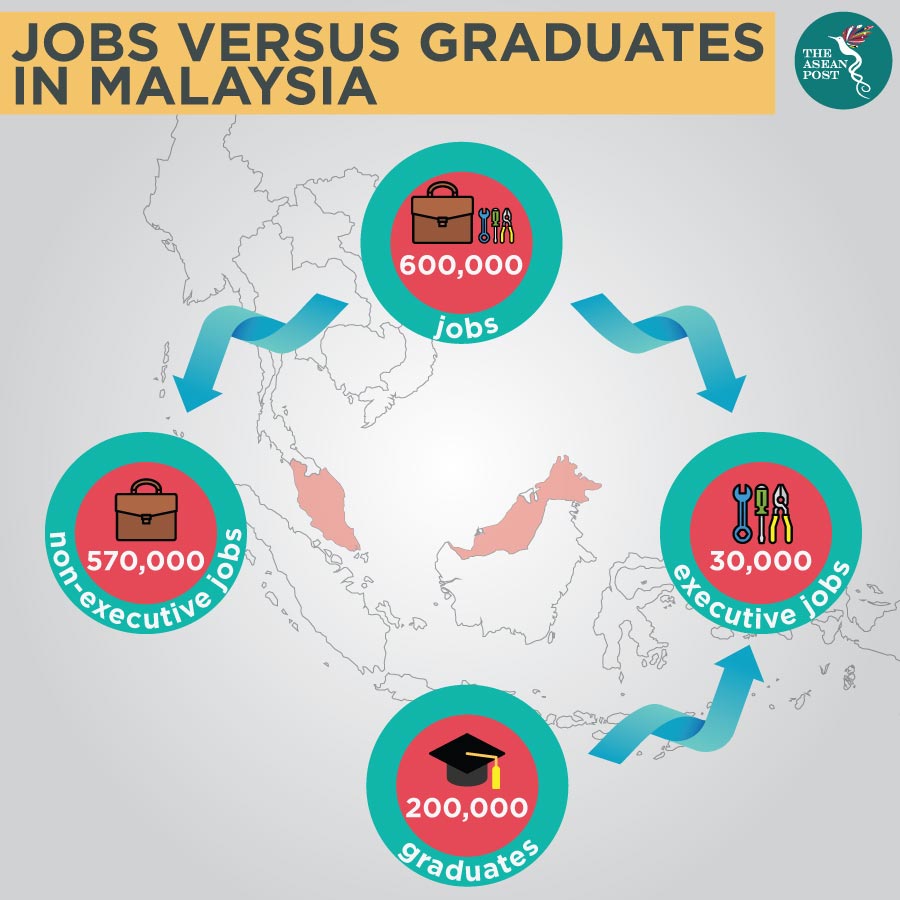

“Of the 600,000 jobs which are mostly lower end, only 60,000 jobs are executive level which attract Malaysians but the main problem here is that there are 200,000 graduates who are looking for jobs,” MEF’s executive director, Shamsuddin Bardan was quoted as saying.

He added that because these positions remain unfilled, employers were forced to employ foreign workers.

“Most Malaysians are not interested in the low-end jobs. Locals prefer higher-end jobs,” Shamsuddin said.

The pay isn’t enough

Shamsuddin seems to suggest that the reason most of these graduates remain unemployed is because they are picky when it comes to job selection. Nevertheless, a news report back in May last year suggests otherwise.

Human Resources Minister, M Kulasegaran was quoted as saying that the lack of Malaysians working in certain sectors is not solely because they are too picky, but because salaries are too low. He said employers should not compare the salaries of foreign workers and locals.

While the minimum wage for Malaysians in the Peninsular is currently RM1,000 (US$241) and will be increased to RM1,200 (US$289) next year, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) says this is nowhere near enough for Malaysians living in the capital city of Kuala Lumpur.

According to BNM, in their annual report for 2017, they said that single citizens should be earning RM2,700 (US$651) a month. Meanwhile, for a family with two children, they should be earning at least RM6,500 (US$1,568) for a living wage. This was two years ago! Factoring in inflation, and the numbers should have increased today.

Quality graduates?

In a previous article, The ASEAN Post noted that five of the country’s institutes of higher learning cemented their places in the top-50 of the Quacquarelli Symonds (QS) World University Rankings: Asia. These universities are Universiti Malaya (13th), Universiti Putra Malaysia (33rd), Universiti Sains Malaysia (37th), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (39th) and Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (46th).

Yet, the problem of graduate unemployment continues.

Malaysia’s Khazanah Research Institute (KRI) noted in a study released last December titled ‘The School-to-Work Transition of Young Malaysians’ that 95 percent of young workers in unskilled jobs and 50 percent of those in low-skilled manual jobs are over-qualified for these occupations. While the BNM has called for the government to create more high-skilled jobs, perhaps the solution in graduate unemployment lies elsewhere.

A KRI survey of Malaysian employers last year found that soft skills – such as creative thinking, flexibility and teamwork – were more important than work experience or hard skills.

In addition, the lack of emphasis on lifelong learning to adapt to the rapidly changing nature and world of work only widens this mismatch.

While Malaysia continues to pump out graduates and, apparently, the country’s universities are top-notch, the question lingers: is Malaysia producing the right types of graduates for the right types of jobs? If the answer to that is “no”, then – aside from telling these graduates to work in low-end jobs they are overqualified for - what is Malaysia going to do about it?

Related articles: