Last week, Malaysian media reported that the country’s finance minister, Lim Guan Eng had handed over an allocation of RM100 million (US$24,646,124) to the minister in the Prime Minister’s Department, Mujahid Yusof Rawa for the purpose of upgrading and maintaining registered Islamic schools.

The allocation is divided into RM50 million (US$12,323,062) for religious Muslim schools (tahfiz schools), RM25 million (US$6,161,801) for public and private Islamic schools and RM25 million (US$6,161,801) for registered hut schools (sekolah pondok). Hut schools don't charge a fee and are run by volunteer teachers.

“The RM100 million (US$24,646,124) allocation reflects the Federal Government’s ongoing commitment to ensure that students enjoy a safe learning and comfortable environment in tahfiz schools, public and private religious schools and pondok schools,” Lim said in a statement.

The keyword in Lim’s statement is, of course, “safe” learning.

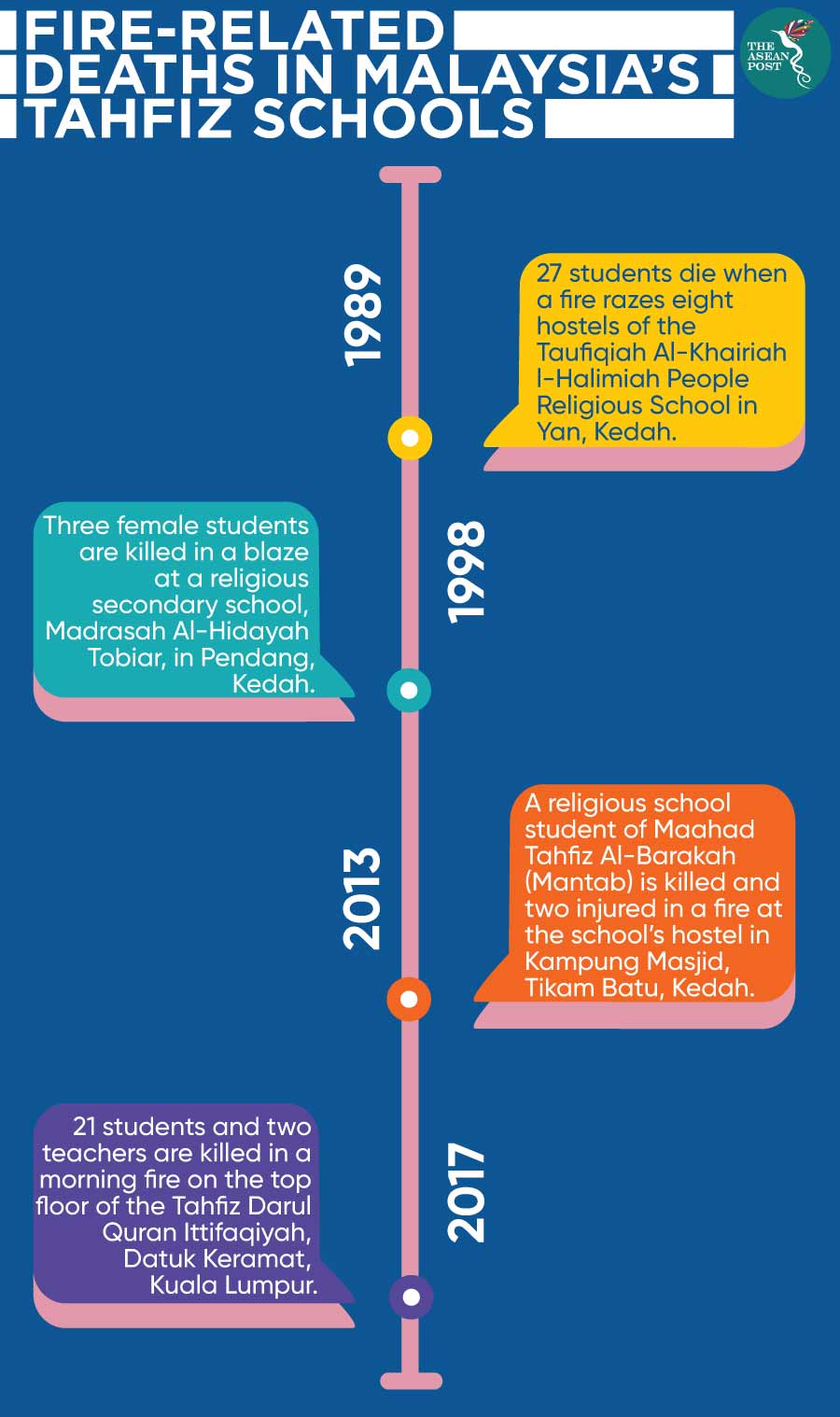

Malaysia’s Islamic schools are infamous for their lack of safety, especially when speaking of tahfiz schools and sekolah pondok. There have been numerous incidents of accidental fires and other mishaps which have resulted in the tragic loss of life.

The most recent of these cases is the infamous Tahfiz Darul Quran Ittifaqiyah fire. The fire that broke out at the tahfiz school at Datuk Keramat, Kuala Lumpur in September, 2017 resulted in the deaths of 21 students and two teachers. Sadly, this is just one of many cases.

The fact of the matter is that it isn’t just fires which have been plaguing these schools. There are also issues such as the case of 11-year-old tahfiz student, Mohamad Thaqif Amin Mohd Gaddafi, who died after alleged abuse at the hands of his school’s assistant warden in Kota Tinggi, a town in the southern state of Johor in Malaysia. The death was reported in April, 2017.

More recently, in September 2019, a tahfiz school in Kuching, the capital of Sarawak - a state in East Malaysia - received heavy criticism on social media regarding a purported parental consent form listing “absurd” forms of punishment for pupils enrolled there. The consent form asked parents to agree to the tahfiz school taking disciplinary action which included 60 strokes of the cane, shaving students’ heads bald, pouring excrement over the students, and standing under the searing midday sun after Zohor (12.42 pm) till Asar (3.56 pm). Zohor and Asar are two out of Islam’s five obligatory daily prayer times.

The form also allegedly noted that those who refused to continue their religious studies would not be given school leaving certificates. Parents were also required to send their children to the school even if they (the children) refused to continue with their religious studies.

In hopes of addressing these types of issues, several non-government organisations (NGOs), civil societies, and human rights advocates have called for Islamic religious schools to be brought under the purview of the country’s education ministry and that it be made compulsory for these schools to be registered under them.

In June 2017, Parent Action Group for Education (PAGE) head, Noor Azimah Rahim was quoted by local media in Malaysia as saying that ideally, anything related to education should be placed under the education ministry.

“The ministry must be able to play some kind of supervisory role and monitor the types of education available in the country. I’m not saying the ministry should impose anything in terms of the schools’ curriculum or even teaching, but it must play a ‘big brother’ role, such as the central bank’s supervision of banks,” she said.

Islamic religious schools are an important symbol of Islamic presence in Malaysia and their prosperity, in turn, represents the prosperity of the religion. The safety of these schools should be made a priority and many observers believe that these schools should be placed under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education. Sadly, this has yet to take place.

The Malaysian government’s allocation for the safety of Islamic schools is indeed welcomed but unless a more permanent solution is found, throwing money at the problem will not make it go away. It is hoped that the Malaysian government will consider the calls of NGOs, civil societies and activists to remedy the situation.

Related articles: