Human-elephant interaction has a rich history dating back centuries which carries cultural symbolism in some places. However, throughout the years that relationship has been altered and the results have been fatal.

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), elephant-human conflict is a result of habitat loss and fragmentation. When elephants and humans interact, there is conflict from crop raiding, injuries and deaths to humans caused by elephants, and elephants being killed by humans for reasons other than ivory and habitat degradation.

India has one of the highest rates of human-elephant conflict (HEC), with nearly 300 people killed annually and an average of 40 to 50 elephants killed during crop raiding.

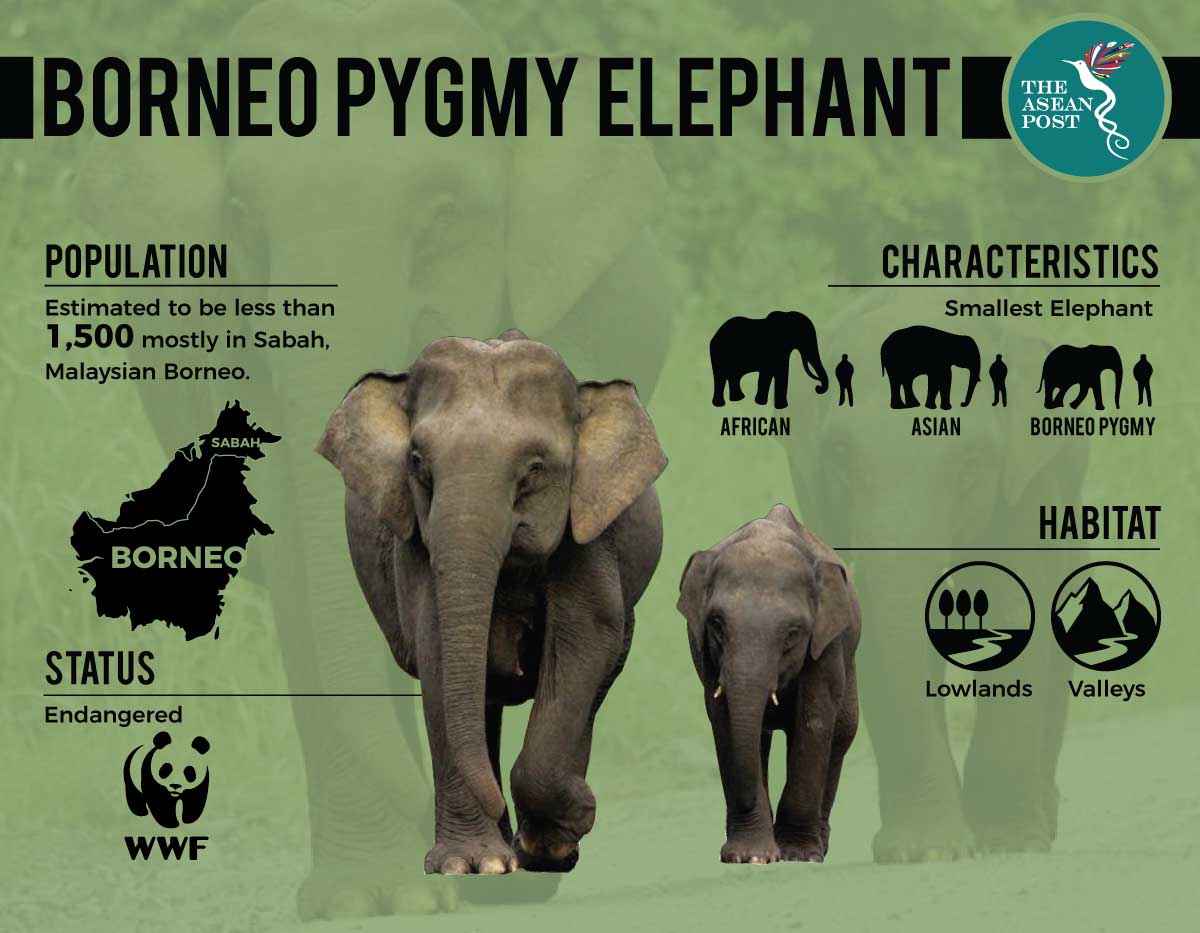

Similarly, the Malaysian state of Sabah located in Borneo has reported 24 pygmy elephants killed in the space of four months in 2019. According to local non-governmental organisation (NGO), Friends of the Earth Malaysia (Sahabat Alam Malaysia or SAM), illegal hunting, poaching, poisoning and snaring are common causes of these elephant deaths. Although accidents do occur, most deaths appear to have been deliberate, retaliatory killings, after the elephants enter into agricultural areas, where crops are eaten and the ground is trampled.

The recent spate of elephant deaths in Sabah, on or near oil palm plantations, has shocked and outraged many. One of the most brutal killings was the incident carried out by two plantation guards and a worker tasked to keep wildlife away from company grounds. The pachyderm's carcass found in Sungai Udin, in the district of Tawau, was riddled with more than 70 bullets. The plantation guards responsible were arrested according to local media.

What are the available solutions?

The Management & Ecology of Malaysian Elephants (MEME) – a joint wild elephant research project by the University of Nottingham Malaysia and the Department of Wildlife and National Parks (PERHILITAN) in Peninsular Malaysia – found that over the last 40 years, Peninsular Malaysia has lost 68 percent of its elephant range to human-occupied landscape, and the remaining 32 percent is in areas near humans, with two-thirds experiencing conflict.

In Malaysia, efforts are divided between preserving the habitats of elephants and protecting plantations. In a recent press statement, SAM argued that elephants have been in Sabah longer than any of the state’s monoculture plantations. Therefore, plantation corporations themselves must be held accountable if any of their employees, permanent or contractual, are proven to be involved in causing harm or death to the endangered animal.

It is unfair and in fact, ineffective, for the law to only punish employees on the ground or security personnel working in these plantations, whose lives may also be directly endangered by HEC, especially if they lack the appropriate training to manage such conflicts. Equally important, is to set a limit to halt the conversions of forests into plantation or agricultural land.

The MEME research project partnered with Sime Darby Plantations, a leading integrated global palm oil company in Malaysia, to endorse a programme that would track and relocate elephants from the plantation zones.

India has adopted resilient conservation efforts and smart application of common technologies to combat the human-elephant conflict since 2014. In 2019, they successfully reduced fatalities to two at the pilot location in the Hassan region, in the state of Karnataka that houses India's largest population of Asian elephants.

They did this by combining an early-warning system using SMS text alerts, automated voice calls, digital signs, and flashing LED lights at key public places across the Hassan region. Forest authorities registered over 35,000 mobile numbers for the pre-warning SMS alert system, as well as from several local WhatsApp groups.

“The conflict between humans and wildlife is caused by competition for food and space and is one of the biggest threats to wildlife around the world. HEC will cause dissatisfaction among those affected, leading to the pressure to translocate elephants from the area," said Abdul Kadir bin Abu Hashim, Director-General of PERHILITAN.

“Through our studies on collared elephants, we now know translocation is not a long-term solution. PERHILITAN has been setting up electric fences to help communities but we will need to explore more ways to help farmers to guard, manage HEC and tolerate having elephants in the landscape,” he added.

Pioneered by the Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), the solution implemented in India does not encourage relocation but instead promotes a collective effort of locals, forest departments and conservationists. SAM wants a similar solution for Sabah.

The NCF stated that winning the trust of locals to implement such a program was the more difficult part. Once the locals trusted their intentions, they were able to equip areas with various gadgets that allowed for efficient live tracking of the elephants. The project has since expanded to 206 villages across 500 square kilometres.

SAM has urged for stronger collaboration among government agencies, civil society and local communities to create a more effective system of managing the ecosystems of Sabah’s elephant habitats. Such a collaboration is urgently needed to curb poaching activities as well as HEC and preserve the state’s wildlife populations.

Related articles: