Aung San Suu Kyi's ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) party took power following a landslide victory in 2015, after five decades of both, direct and indirect military rule.

Suu Kyi, however, could not be named president due to Article 59(f) of the constitution, which bars a person from becoming president if his or her spouse or children are foreign citizens. Her two sons are British nationals, as was her late husband.

Suu Kyi and her party were able to surpass this rule because of a legal loophole which allowed the creation of the post of State Counsellor, the equivalent of Prime Minister, to which she was appointed – thus, giving her executive power, while the post of President was filled by NLD member, Win Myint.

On Wednesday, Myanmar's parliament rejected a proposed constitutional amendment that would have allowed Suu Kyi to officially become President. The rejection had been expected as it was opposed by the military, which – under the constitution – holds enough seats to block any constitutional change.

The defeated motion was one of several constitutional changes proposed by Suu Kyi’s ruling NLD party. The other changes are also expected to be blocked.

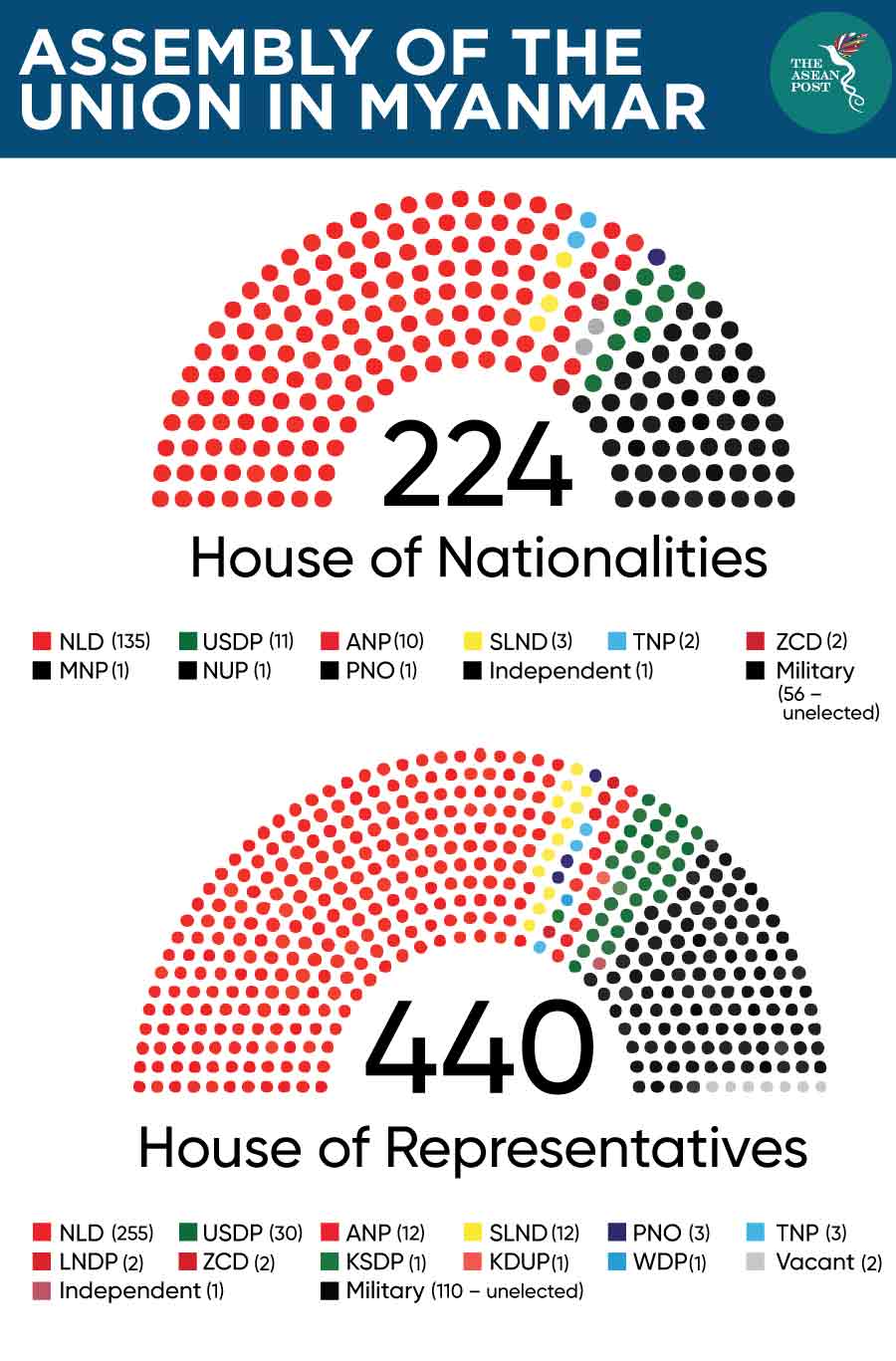

Despite talks of progress in democratisation of the country, Suu Kyi is still constrained by the 2008 constitution, which secured the untouchable power of the military and guaranteed it 25 percent of all parliamentary seats.

Any constitutional change requires the approval of more than 75 percent of the members of the combined houses of parliament. Members of the military can usually also count on the support of civilian opposition parties allied with it; the Union Solidarity and Development Party. Therefore, while Suu Kyi is deemed responsible for the government’s actions, she does not have the actual power to institute political reforms.

Suu Kyi’s enduring domestic support can be attributed to her achievement of the impossible. Nonetheless, the constraints put in place by the military-based political system impedes her ambitions toward further democratic consolidation.

Such indicators of progress would include lifting repressive laws such as the regulation on freedom of assembly, and revising the controversial Telecommunications Law, which has been used to muzzle journalists – and even silence Suu Kyi not too long ago.

“The global expectations placed on her were unrealistically high,” said Benedict Rogers, leader of the East Asia team at human rights organisation, the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW), who has met Aung San Suu Kyi multiple times.

Headlines in 2017 were dominated by the Rohingya tragedy that has seen more than 700,000 flee to Bangladesh. In addition, Suu Kyi is also faced with increased attacks from rebel ethnic groups – the ongoing civil war is prevalent across Kachin, Rakhine, and Shan states in the north of the country.

In December 2019, Suu Kyi defended Myanmar's military against genocide allegations at the International Court of Justice (ICJ), amid accusations of mass killings, rape and expulsion of the mostly Muslim Rohingya minority.

In her speech at The Hague, Suu Kyi referred to the Rohingya as Muslims, people, civilians and members of Rakhine communities. Her refusal to use the term 'Rohingya' and providing a proper explanation disappointed the global audience, which undoubtedly expected much more from the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize winner who spent 15 years under house arrest.

“I am just a politician,” she said in a 2015 interview. “I am not quite like Margaret Thatcher, no. But on the other hand, I am no Mother Teresa either. I have never said that I was.”

Although Suu Kyi's government has produced the comprehensive 'Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (2018-2030)' aimed towards a peaceful, prosperous, and democratic Myanmar, it is nonetheless a framework that is highly unlikely to grant democracy to the nation. After five years in office, there is genuine doubt if Suu Kyi is still the right person to bring change to Myanmar – let alone represent it at the ICJ genocide probe.

Related articles: