In late January, Cambodia's Prime Minister, Hun Sen, made a televised statement about the spread of misinformation regarding the COVID-19 virus outbreak originating from Wuhan, China. He also threatened to “kick out” reporters or officials seen wearing a face mask.

He said that the real illness was the fear they faced from inaccurate information spreading on social media. At the time, the country had only one confirmed COVID-19 case – a Chinese man who had travelled to Cambodia from Wuhan.

Hun Sen called for citizens not to discriminate against the Chinese, as the country hosts many Chinese investors and tourists. “There is no one who died, and not a single Cambodian contracting the virus, it happened only to a Chinese man," he reassured.

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported 17 arrests made since late January for sharing information about the coronavirus in Cambodia. These include four members or supporters of the dissolved opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), all of whom remain in pre-trial detention. A 14-year-old girl who expressed fears on social media about rumours of positive COVID-19 cases at her school was also arrested and questioned. 12 of those arrested have so far been released from detention after signing pledges to not spread “fake news” in the future and to apologise.

In the following weeks, most confirmed COVID-19 cases were foreign nationals, and by the second week of March, new infections doubled from 12 to 24. “Of the 12 infected, 11 are Khmer Muslims and were among 79 who returned from a Muslim religious event near Kuala Lumpur [Malaysia],” local media reported.

A similar narrative was used as the number of infections rose, this time it fuelling discriminatory actions against Khmer Muslims.

According to the HRW, when the Health Ministry posted a COVID-19 cases update on its official Facebook page on 17 March, 2020, they made reference to specific groups of people who had contracted the virus, including “Khmer Islam.” This post led to an outburst of discriminatory and hateful comments online. Similar behaviour was also observed in daily interactions at markets, shops, and community areas against Cambodia’s minority Muslim communities.

The Cambodian government’s system of categorising patients according to their ethnicity and religion is certainly questionable. In a wider context, one can only imagine the repercussions if a similar system was adopted in the United States (US) or in Europe. If governments there were to update COVID-19 cases based on ethnicity or religion, it would undoubtedly spark fierce debate and discrimination – especially considering the racist treatment that ethnic Chinese have been experiencing since the beginning of the outbreak.

The HRW now reports that the government of Cambodia has stopped referring to some locals as “Khmer Islam" but by a more general "Khmer". Sadly, Hun Sen's government has not made any statement to reverse the effects of the rather harmful initial public response.

Members of the public have posted hateful social media comments in reaction to the Health Ministry’s original statement, blaming Cambodia’s Muslim communities for the spread of the virus in the country. Cambodian Muslims, particularly in Phnom Penh, have since reported facing discrimination, such as people refusing to sell or buy products from them, or to even exchange money. Others have reported that non-Muslim Cambodians put on face masks as soon as they see Muslim Cambodians coming into their vicinity.

This has also been the case for foreigners residing in the country. The banning of foreigners coming to Cambodia from Europe and the US – in addition to the government's narrative that foreigners are responsible for the spread of the deadly virus – has resulted in expatriates reporting a rise in discriminatory actions against them.

Expatriates have increasingly reported on social media that they have been denied entry into shops and establishments in Phnom Penh. The government has not taken any action despite instances where shop owners have posted signs in English refusing entry or service to foreigners. Some local shops have also resorted to use English signs claiming the shop was closed while Khmer language signs indicate the shop was “open as usual.”

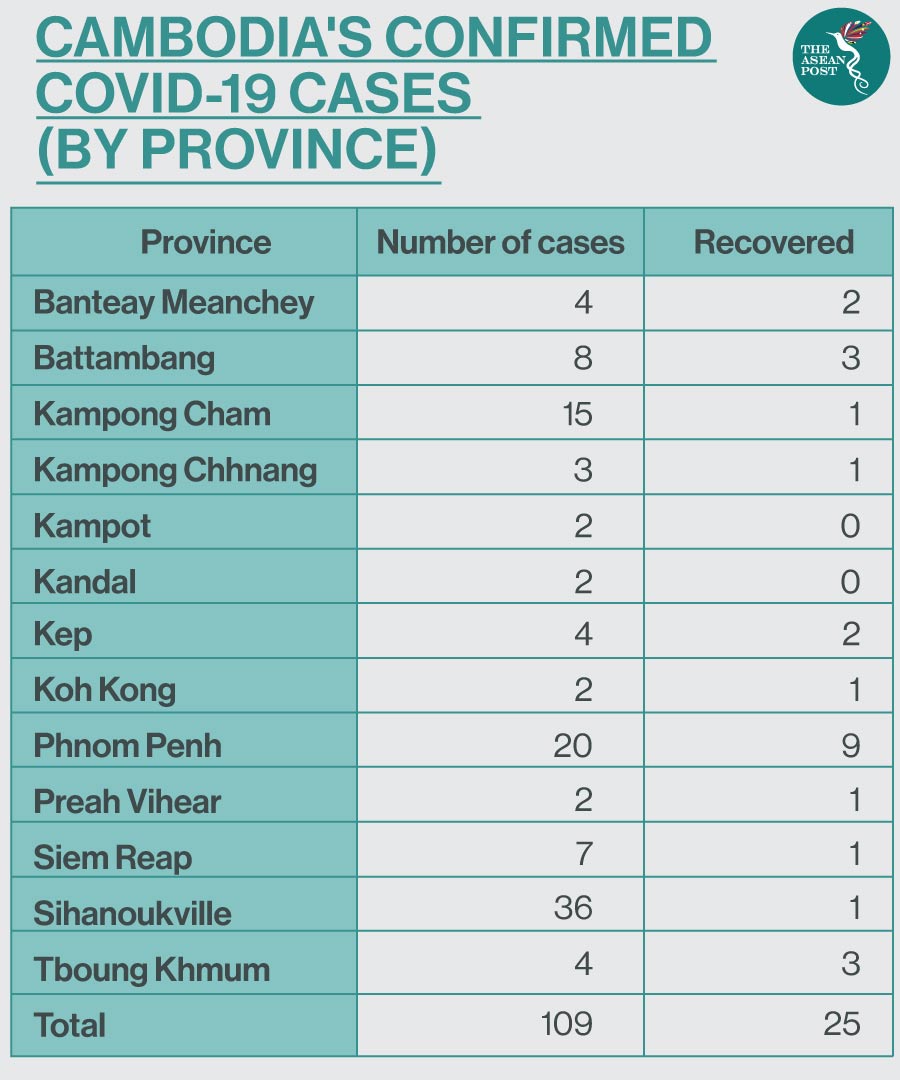

As of 1 April, 2020, Cambodia has a total of 109 COVID-19 cases – 49 locals and 60 foreigners – with zero deaths reported. Like all the 203 countries affected by the outbreak – excluding China – cases of COVID-19 started with imports which then led to local transmissions. It is the precautionary health measures taken by the respective countries that will determine if the number of cases surge uncontrollably or are contained effectively.

Cambodia is so far among the bottom 50 percent of countries in terms of COVID-19 cases, both globally and among ASEAN countries. Compared to the top 50 percent in the world, that is an achievement and yet it does not erase the extremely high risks constantly present as infections can surge overnight in developed as well as developing nations.

Human rights issues should be dealt with immediately by the Cambodian government; clearing the air of any blame or prejudice for the outbreak against any one group. The crisis that the entire global community is currently facing is indiscriminatory in nature, possessing the potential to wreak further chaos and disruptions in our socio-economic environment without systematic efforts by governments to contain it.

Related articles: