The global backlash against China over its culpability for the international spread of the deadly coronavirus from Wuhan has gained momentum in recent weeks. And China itself has added fuel to the fire, as exemplified by its recent legal crackdown on Hong Kong. From implicitly seeking a political quid pro quo for supplying other countries with protective medical gear, to rejecting calls for an independent international inquiry into the virus’s origins until a majority of countries backed such a probe, the bullying tactics of President Xi Jinping’s government have damaged and isolated China’s communist regime.

The backlash could take the form of Western sanctions as Xi’s regime seeks to overturn Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” framework with its proposed new national-security laws for the territory, which has been wracked by widespread pro-democracy protests for over a year. More broadly, Xi’s overreach is inviting increasing hostility among China’s neighbours and around the world.

Had Xi been wise, China would have sought to repair the pandemic-inflicted damage to its image by showing empathy and compassion, such as by granting debt relief to near-bankrupt Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) partner countries and providing medical aid to poorer countries without seeking their support for its handling of the outbreak. Instead, China has acted in ways that undermine its long-term interests.

Whether through its aggressive “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy – named after two Chinese films in which special-operations forces rout United States (US)-led mercenaries – or military-backed expansionist moves in China’s neighbourhood, Xi’s regime has caused international alarm. In fact, Xi, the self-styled indispensable leader, views the current global crisis as an opportunity to tighten his grip on power and advance his neo-imperialist agenda, recently telling a Chinese university audience that, “The great steps in history were all taken after major disasters.”

China has certainly sought to make the most of the pandemic. After buying up much of the world’s available supply of protective medical equipment in January, it has engaged in price-gouging and apparent profiteering. And Chinese exports of substandard or defective medical gear have only added to the international anger.

While the world grapples with COVID-19, the Chinese military has provoked border flare-ups with India and attempted to police the waters off the Japanese-controlled Senkaku Islands. China has also recently established two new administrative districts in the South China Sea, and stepped up its incursions and other activities in the area. In early April, for example, a Chinese coast guard ship rammed and sank a Vietnamese fishing boat, prompting the US to caution China to “stop exploiting the [pandemic-related] distraction or vulnerability of other states to expand its unlawful claims in the South China Sea.”

Meanwhile, China has made good on its threat of economic reprisals against Australia for initiating the idea of an international coronavirus inquiry. Through trade actions, the Chinese government has effectively cut off imports of Australian barley and blocked more than one-third of Australia’s regular beef exports to China.

Whereas Japan readily allowed the International Atomic Energy Agency to conduct a full investigation into the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster – a probe that helped the country to improve safety governance – China strongly opposed any coronavirus inquiry, as if it had something to hide. In fact, some Chinese commentators denounced calls for an inquiry as racist.

But once a resolution calling for an “impartial, independent and comprehensive evaluation” of the global response to COVID-19 gained the support of more than 100 countries in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) decision-making body, the World Health Assembly, Xi sought to save face by telling the assembly that “China supports the idea of a comprehensive review.” At the last minute, China co-sponsored the resolution, which was approved without objection.

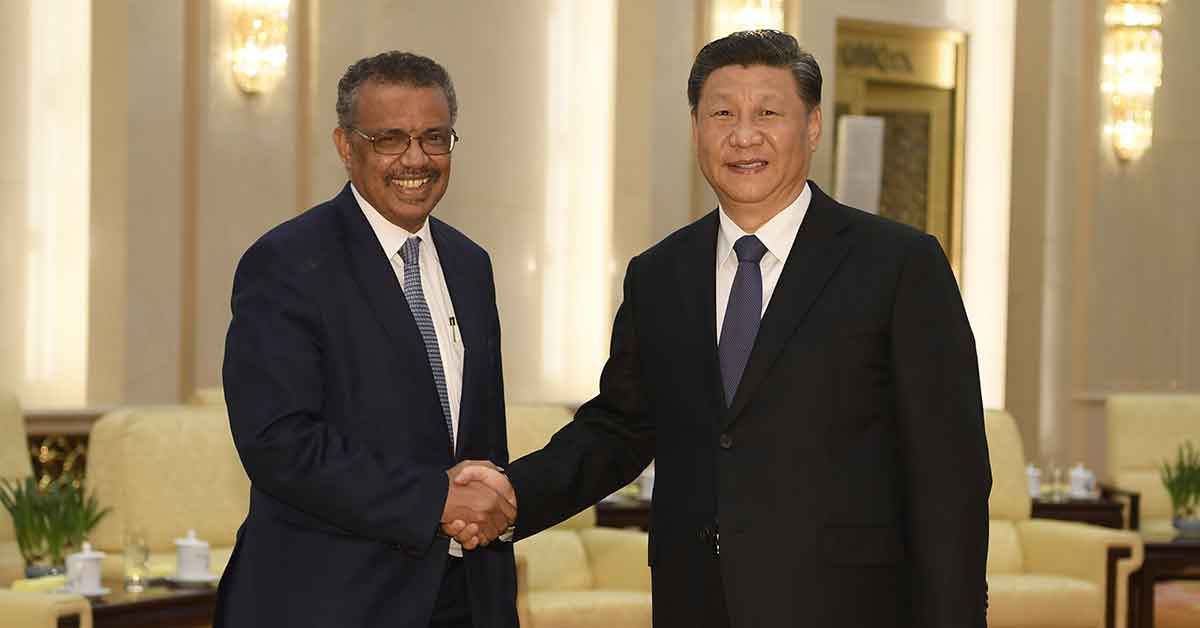

The resolution, however, leaves it up to the WHO’s controversial director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, to launch the review “at the earliest appropriate moment.” Tedros, who has been accused of aiding China’s initial COVID-19 cover-up, may decide to wait until the pandemic has come “under control,” as Xi has proposed.

Make no mistake: the world will not be the same after this wartime-like crisis. Future historians will regard the pandemic as a turning point that helped to reshape global politics and restructure vital production networks. Indeed, the crisis has made the world wake up to the potential threats stemming from China’s grip on many global supply chains, and moves are already afoot to loosen that control.

More fundamentally, Xi’s actions highlight how political institutions that bend to the whim of a single, omnipotent individual are prone to costly blunders. China’s diplomatic and information offensive to obscure facts and deflect criticism of its COVID-19 response may be only the latest example of its brazen use of censure and coercion to browbeat other countries. But it represents a watershed moment.

In the past, China’s reliance on persuasion secured its admission to international institutions like the World Trade Organization (WTO) and helped to power its economic rise. But under Xi, spreading disinformation, exercising economic leverage, flexing military muscle, and running targeted influence operations have become China’s favourite tools for getting its way. Diplomacy serves as an adjunct of the Communist Party’s propaganda apparatus.

Xi’s approach is alienating other countries, in the process jeopardising their appetite for Chinese-made goods, scaring away investors, and accentuating China’s image problem. Negative views of China and its leadership among Americans have reached a record high. Major economies such as Japan and the US are offering firms relocation subsidies as an incentive to shift production out of China. And India’s new rule requiring prior government approval of any investment from China is the first of its kind.

China currently faces the most daunting international environment since it began opening up in the late 1970s, and now it risks suffering lasting damage to its image and interests. A boomerang effect from Xi’s overreach seems inevitable. A pandemic that originated in China will likely end up weakening the country’s global position and hamstringing its future growth. In this sense, the hollowing out of Hong Kong’s autonomy in the shadow of COVID-19 could prove to be the proverbial straw that breaks the Chinese camel’s back.

Related Articles: