Geostrategic tensions, global mistrust and the dark side of the digital world are significant threats that could fracture the world, according to the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General during the UN General Assembly in September 2020. These threats stem from the strategic competition between the United States (US) and China, which risks fuelling a new Cold War that could ‘split the globe’.

These threats also coalesce into Technationalism, which is a mercantilist conduct that both great powers embrace and could undermine the globalist ideals of cooperation towards a shared future for all countries.

This conduct augments the national security, economy and socio-political values of one great power at the expense of the other. The impact of this conduct would reverberate across Southeast Asia, which both great powers regard as a strategic arena in their contest for geopolitical influence in the Asia-Pacific.

Technationalism will affect Southeast Asia

President Trump’s ‘America First’ and President Xi Jinping’s ‘Made in China 2025’ are two competing visions of Technationalism. In Technationalism, trade and technology deviate from their purposes as enablers of international cooperation. They instead become instruments of compellence for the great powers to wage economic warfare against each other.

The US has instituted an aggressive global campaign against what it deems as China’s unfair policies and practices that threaten the free world. China’s responses to the US’ campaign increasingly include symmetrical countermeasures. For example, China’s ‘Global Initiative on Data Security’ challenges the US’ ‘Clean Network Initiative’ that aims to chip away at Chinese dominance in 5G technologies and capacity to shape global technological standards.

China's introduction of its 'Unreliable Entity List' aims to challenge US' efforts that could cripple Chinese technology giants such as ByteDance, Tencent and Huawei.

As the US and China are both vital trade partners of Southeast Asia, the region would inevitably face the knock-on effects from the great powers’ erratic behaviour and tit-for-tat actions against each other. For example, Southeast Asian countries might have to navigate a complex digital fracture resulting from technological bifurcation if they leverage the digital economy to better tap opportunities in Chinese and American markets.

Even now, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s visit to Southeast Asia in October 2020 and the US’ Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s participation in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations’ (ASEAN) meetings in September 2020 are diplomatic overtures by both great powers to encourage countries in the region to take sides. Secretary Pompeo, for example, had urged Southeast Asian countries to reconsider agreements with some Chinese companies that the US had blacklisted.

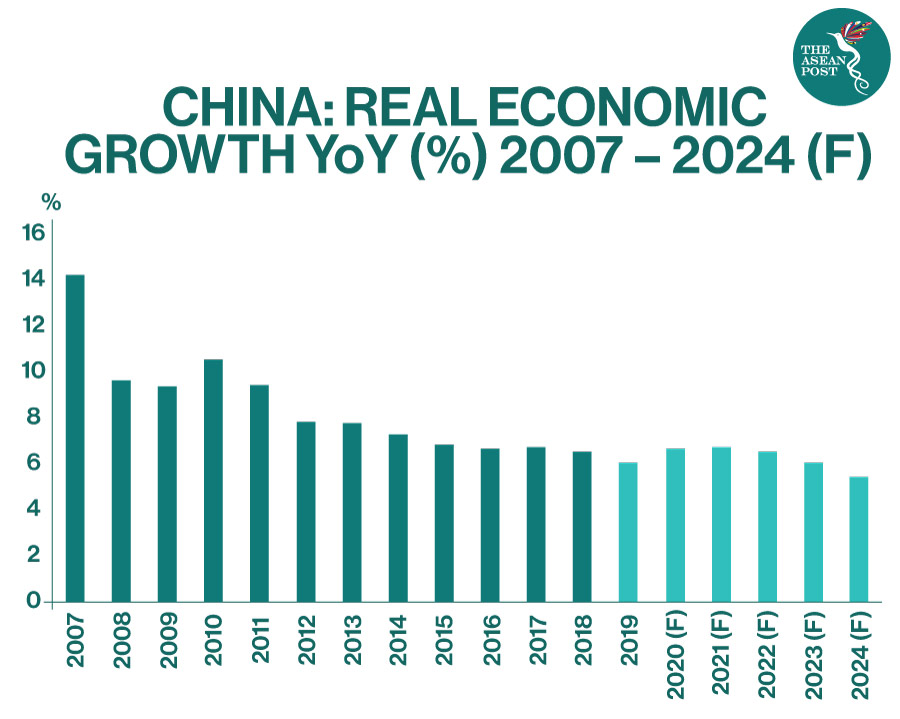

However, geographical proximity and the size of China’s economy make it necessary for Southeast Asian countries to maintain meaningful relations with China while balancing its influence vis-à-vis the US. Furthermore, it is impractical to side-line China as it is the only major economy that has achieved positive growth amid the COVID-19 crisis.

Southeast Asian countries face the daunting and endless challenge of convincing the great powers that the region has not and would not take sides. However, if western-centric hawks frame the growing presence of Chinese technology giants in Southeast Asia as an entrenchment of the Digital Silk Road, the US might perceive the region as a weak link in its network of allies and partners.

Furthermore, the US might also focus some coercive economic policies on Southeast Asia if businesses and technology suppliers are relocating to the region more than reshoring to the US. If Sino-centric hawks perceive any difficulties hampering the ‘China Plus One’ strategy as the region answering the US’ call to stand up to China, the region could face repercussions.

For example, Australia is an important trading partner of China. Yet, it has met with Chinese diplomatic and economic retaliation for purportedly siding with the US in blaming China for the spread of COVID-19.

Given the strategic importance of Southeast Asia to both great powers, the region could become an epicentre of their competing influence campaigns and intelligence activities. As technology – infrastructure, services, talent and capital – is crucial for economic growth, Southeast Asian countries would need to enhance measures to manage the risks of supply chain disruptions. These measures could include designating tech-related home-grown and locally-based multinational companies as strategic assets.

A great power, however, might view these companies as proxy threats if they conduct business that implicitly benefits the grand strategy of the opposing power. For example, the US in 2018 blocked Singapore-based Broadcom from acquiring Qualcomm due to national security concerns that the deal might spur Chinese dominance in 5G technologies.

Navigating The Turbulence Of Technationalism

A Southeast Asia that is polarised by US-China Technationalism would economically disadvantage countries in the region and ultimately affect trade relations and technological collaboration with both powers. Southeast Asian states should be more united in facing US-China Technationalism to protect their national and ASEAN-centric interests rather than be swayed by US-centric or Sino-centric biases. There must be clarity on what their common technological, economic, and national security interests are.

On the technology side, Southeast Asian countries as collectively a significant user of 4G and 5G technologies should project a more prominent voice in the setting of technological and cybersecurity standards – such as Security by Design. This voice is increasingly crucial as countries embrace more digitalisation and smart city solutions to restructure their economies in riding out the economic impact of COVID-19.

A 2018 World Economic Forum’s (WEF) White Paper, ‘Shaping ASEAN’s Future Readiness’ highlighted that such standards are essential for interoperability of systems and seamless flow of data if the region seeks to achieve a ‘single digital market’.

Furthermore, this voice could both represent a multilateral bulwark by Southeast Asian countries against the rising tide of US-China rivalry and serve as a much-needed bridge if the world splits into two politico-economic blocs.

On the economic side, governments and industries in Southeast Asia need to examine their exposure and vulnerabilities to the policies of the US and China. This examination should include assessing intra-regional vulnerabilities resulting from great power rivalry. Southeast Asian countries should guard against Technationalism taking focus away from national plans to boost internet connectivity and uplift living standards, especially among more impoverished communities in the region.

Greater regionalisation of technological supply chains is needed to hedge against the risks of coercive economic actions by the great powers and rising business costs resulting from the fragmentation of the global economy.

Countries should also focus on building up more indigenous capabilities in strategic areas such as telecommunications and artificial intelligence, which are vital to the ASEAN vision of Industry 4.0.

On the national security side, Southeast Asian countries should be careful not to be deeply drawn into the US-China technological rivalry. This rivalry should not be allowed to become the next contentious issue – besides the South China Sea dispute – to undermine ASEAN unity.

The aggressive policies of the US and China to counter each other are based on strategic perceptions and realities that could be different from those of Southeast Asian countries. Also, Technationalism is often portrayed by the US as an ideological conflict between the values of liberal democracy and digital authoritarianism as 5G technologies enable stronger surveillance powers and social governance.

Instead of being swayed by ideological rhetoric of the great powers, Southeast Asian countries should have clarity on the acquired socio-political values that define their nationhood and hence must be defended.

These strategies might work well for some if not all Southeast Asian countries. Nonetheless, Southeast Asia needs to start somewhere to navigate the rising turbulence of US-China Technationalism better.

Related Articles: