At the United Nations (UN) General Assembly this September, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that China aims to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. Given that China has been the planet’s single-largest source of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in recent years – accounting for about 30 percent – decarbonisation there could contribute substantially to the global effort to mitigate climate change.

China, of course, will have to rebalance its economy. Among other things, that means shifting from manufacturing to services, from capital-intensive to innovation-led activity, from exports to domestic demand, and from investment to consumption. All of these changes are mutually reinforcing, such that delivering on one facilitates progress on the others.

More to the point, rebalancing will also contribute to China’s energy transition, by shifting from energy-intensive to energy-light activity. For example, if capital and labour move from the production of steel, cement, and industrial goods to the provision of education, health care, and leisure opportunities, the economy should gradually consume less energy for each unit of gross domestic product (GDP) produced.

When assessing China’s prospects for attaining President Xi’s target for carbon neutrality, one first must consider how large its economy will become. S&P Global Ratings expects China’s GDP to grow at an average annualised rate of 3.6 percent over the next two decades.

This may seem low given the track record since 1990, but our projection is rooted in careful assumptions about the economy’s supply side, with the slowdown driven by a shrinking workforce, lower investment, and weaker productivity growth. The richer an economy becomes, the more slowly it tends to grow.

China is anomalous among major economies insofar as private consumption still comprises a small share of total spending. Hence, our growth forecasts assume that private consumption will increase from less than 40 percent to 55 percent of total spending in 2040, with investment undergoing a similarly sized decline.

As consumers become richer and more important for the economy, the demand for services rises relative to demand for goods. In our forecasts, we find that Chinese service-sector output (in real terms) will grow by an annualised rate of 5.2 percent, also over the next two decades, almost double the rate of industry (2.7 percent).

This shift in final demand will ripple through the domestic supply chain. For example, if China invests less in physical infrastructure like roads and airports, it will need less steel, and thus less coal. An economy driven by consumer spending is less carbon-intensive than one geared toward heavy industry and manufacturing for export.

We have applied this rebalancing scenario to the S&P Global Platts Analytics Global Integrated Energy Model to see what it might mean for China’s efforts to become carbon neutral by 2060. This model balances end-use energy consumption against available fuel supply, shedding light on energy use across industries as well as on CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel combustion.

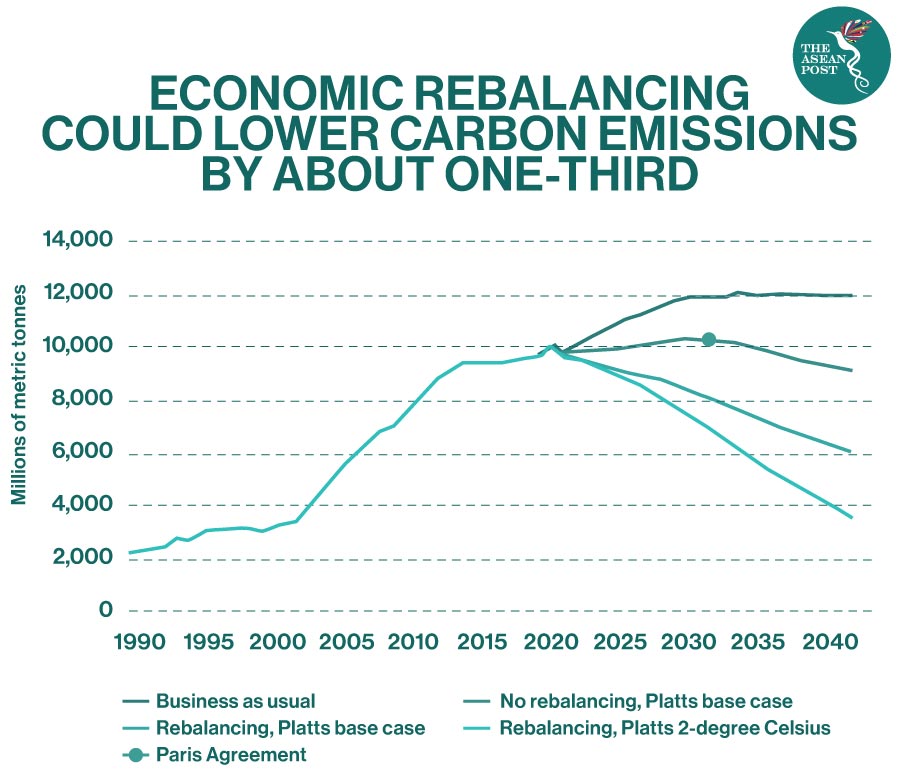

We consider four energy-use scenarios for China. The first assumes no economic rebalancing and no change in energy intensity. The second and third compare how economic rebalancing will affect energy demand under the most likely baseline case, where existing trends in energy efficiency and use of renewables continue. The fourth considers economic rebalancing alongside a more challenging “2-degree Celsius scenario” that aggressively reduces the use of carbon-intensive fuels in line with the Paris agreement.

We find that economic rebalancing alone could lower China’s CO2 emissions by an additional 32 percent by 2040 (see chart). And if China pursued a 2-degree Celsius goal by accelerating its transition to renewables, our model points to an even more dramatic fall of 61 percent in emissions.

Rebalancing lowers emissions most directly by reducing the overall economy’s energy intensity by 20 percent by 2040 (compared to the no rebalancing scenario).

But we can also assess the impact of rebalancing through the lens of end-use sectors. Even under extreme low-carbon modelling assumptions, industrial end-use sectors will be slower to decarbonise, so shifting away from these sectors towards consumption and services accelerates the transition.

Our scenarios are plausible but tough. With consumption as a share of the Chinese economy having risen by less than five percentage points over the past decade, it will now have to increase twice as fast in order to achieve a 55 percent share by 2040.

From an energy perspective, a substantial policy effort is needed to reduce carbon intensity end-use across transportation, power generation, and other sectors. This could take the form of further restrictions or even a ban on the sale of internal-combustion vehicles, higher energy efficiency targets, incentives for retrofitting buildings, and investment in nationwide electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure.

We do not directly model the impact of fuels like hydrogen, nor the potential effect of carbon capture, utilisation, and storage technologies. Both might come to play a key role by 2060.

We will learn more about China’s chances of success early next year when it publishes its 14th five-year plan (for 2021-2025). If its policy blueprint paves the way for consumers to increase spending towards advanced-economy levels, achieving carbon neutrality will become much easier. Still, China will need to make some hard decisions on coal in order to meet our model’s 2-degree Celsius assumptions, and to put itself on a firmly sustainable path.

Mark Mozur and Alan Struth from S&P Global Platts also contributed to this column.

Related Articles: