With the reimposition of the movement control order (MCO 2.0) in Malaysia which impacts the economy – though less severe compared to MCO 1.0 – we may be witnessing the beginning of a housing loans crisis in the making. This near-apocalyptic scenario may not sound palatable for banking stocks and could well be just hypothetical. But we need to ensure such a hypothetical scenario can be averted and also simultaneously prepare to mitigate the fallout should pre-emption be not possible.

The backdrop to this is Malaysia being well-known as having one of highest household debt ratios in Asia and the highest in ASEAN. Looking at the data, the country’s household debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio was reported at 82.2 percent in June 2019. The Central Bank of Malaysia’s (BNM) Financial Stability Review (Second Half, 2019) highlighted that the household indebtedness level increased to 82.7 as at the end of 2019, driven by housing loans. According to BNM’s Financial Stability Review (First Half, 2020), household debt-to-GDP ratio rose to 87.5 percent by June 2020.

The one indicator or proxy to relatively measure the capacity to sustain loan repayment is of course the level of unemployment and under-employment. As has been emphasised by economists and commentators, rising unemployment and under-employment inevitably means reduced capacity to repay debt, principally in the form of housing loans.

MCO 2.0 will mean that unemployment (and under-employment) figures are set to rise again – from the current level of below five percent. The latest figures from the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) are for the month of November 2020 at 4.8 percent which translates into 764,400 unemployed persons. The five percent threshold which hovered over the economy for the past one year could be breached this year, perhaps by 1Q 2021.

If unemployment rises to six percent by the first half of the year – 1H 2021 – this would then roughly translate into nearly a million jobless people. It’s still a conservative estimate as forecasted by economists such as Anthony Dass, AmBank Group chief economist and member of the Economic Action Council secretariat in relation to the year-end of 2020, i.e., in the absence of an MCO as such and on the presumption of the recovery movement control order (RMCO) in place. What it means is that with the implementation of MCO 2.0 considered together with its extension, the unemployment figures – underpinned by sustained and continuing recession (in place since 2Q 2019) – can only continuously grow even if at a slow pace.

The other critical part is, of course, the price-to-annual income ratio which currently is at 6.2 times since 2016. BNM has highlighted that properties in the country are not affordably priced based on the current median income. This means there is a mismatch between current or prevailing market prices of residential property with the average income level.

Those servicing their housing loans typically are supposed to allocate at most one-third of their wages for the monthly instalment. But anecdotal evidence suggests that it could be up to half of the take home pay, realistically speaking.

Now this is simply because of the saving and spending habits of the average Malaysian, especially urbanites who by now comprise the majority of the population which stands at 77 percent based on a 2019 World Bank figure.

According to the Malaysian Financial Literacy Survey conducted by financial comparison website, RinggitPlus (2018), as many as 59 percent of Malaysians do not have enough savings to last them for more than three months, and that 34 percent admitted to spending equal to or more than their monthly salary. The Middle 40 percent (M40) as the majority of house buyers and owners are squeezed by a combination of high cost of living and critically, very low savings. The same survey highlighted that 67 percent of Malaysians earning between RM5,000 (US$1,236) to RM10,000 (US$2,473) a month save less than RM1,000 (US$247) monthly.

This is why in 2020, the Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) urged the Finance Ministry and BNM to ask banks to consider extending the moratorium on loan repayments by at least another six months – from 1 October, 2020 onwards.

The Congress of Unions of Employees in the Public and Civil Services (CUEPACS) had also called for loan deferment for borrowers under the Public Sector Home Financing Board (LPPSA).

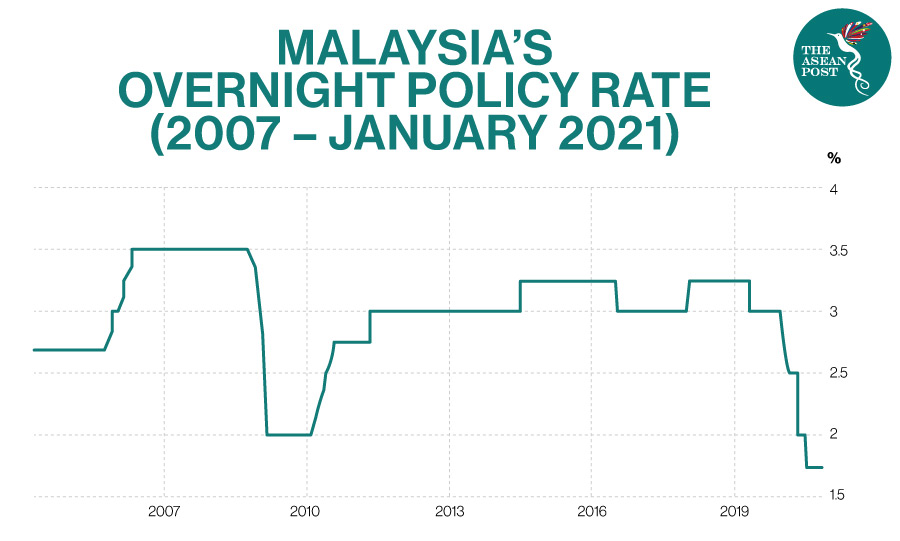

Ultimately, it’s the price of the housing and hence the level of the loan burden that is the elephant in the room. The concomitant reduction in the loan interest rate will not make much of a difference for those who have to endure a pay cut, for example.

In the final analysis which is simply a reiteration of what’s been highlighted time and again, house prices in Malaysia have yet to reflect demand of buyers in terms of affordability and income levels in general. Whilst Malaysia seems immune to a housing bubble (based on past experience and current trends), when it comes to non-performing loans (NPLs) under housing, it is not – again for the reasons explained above.

The rise in NPLs will affect banks’ earnings which in turn might affect the bank’s leverage ratio, i.e., capacity to generate new loans, and by extension impacting on the overall liquidity in the markets with serious repercussions for the health of the economy.

Therefore, the following are some recommendations:

Crisis Aversion

Steps need to be taken to re-extend the loan moratorium backdated with effect from 1 January 2021 till 30 June, 2021. Or adjust the moratorium into loan discounts of up to 50 percent for six months from the same date. The remainder will be repaid for another six months after the end of the loan period as in the agreement.

As in the loan moratorium, compound interest should not be charged for this six-month period.

The COVID-19 (Temporary Measures) Act (2020) didn’t include provisions to protect homeowners from foreclosures, i.e., when they default on their loans, e.g., until the end of 2021. Together with this should also be enforced loan refinancing measures or restructuring and rescheduling of the loan agreement upon the lending banks.

Crisis Preparedness

The National Mortgage Corporation of Malaysia (Cagamas Bhd) should be deployed to buy and take over (what remains of) the housing loans with the potential of NPLs.

Several options should be made available such as offering between zero and 0.5 percent interest rates to house owners. This could stand-alone or be packaged together with the implementation of its shared equity scheme – which has been in the works since the second quarter of 2019.

The scheme could be implemented by increasing Cagamas’ share of co-funding from 20 percent to 40 percent. This scheme would then take place with immediate effect. This means the existing loan is converted into the scheme.

To protect banks’ earnings and minimise the one-off Day One modification loss, which is an accounting standard procedure meaning loss relating to the “opportunity cost over time from not having received the additional cashflow”, it is proposed that tax holidays and exemptions be given.

And BNM could provide loans at zero interest to the affected banks, if need be.

To conclude, the double whammy of defaulted loans by buyers in the housing sector alongside the impact on lender banks should motivate the government of Malaysia to do something.

The price of inaction or complacency is perhaps something we can’t afford given the unprecedented nature of COVID-19 which is fast-forwarding and accelerating this emerging problem.

Related Articles: