The South China Sea (SCS), one of the most in-demand waterways in the world, is the object of contention of several claimant-states with overlapping territorial and maritime sovereignty and sovereign rights claims over its disputed waters. The said dispute is still unresolved until today and can be dated back to the 1950s. It is based on historical and geographical accounts and varying interpretations of international law by the claimant-states.

Fundamentally, the claimants of the SCS primarily struggle and compete over sovereignty with no straightforward and trouble-free legal remedy and antidote. Aside from sovereignty-related issues, another point of contention over the SCS is who has exclusive rights over the abundant oil reserves and plenteous fishing stocks and marine resources of the SCS.

Some claimants base their claims of an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) on historical grounds while others refer to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea treaty.

Furthermore, tensions over the SCS dispute have been heightened by unbridled nationalism and megaphone diplomacy, and by the great power rivalries and competition between the United States (US) and China in the Indo-Pacific region.

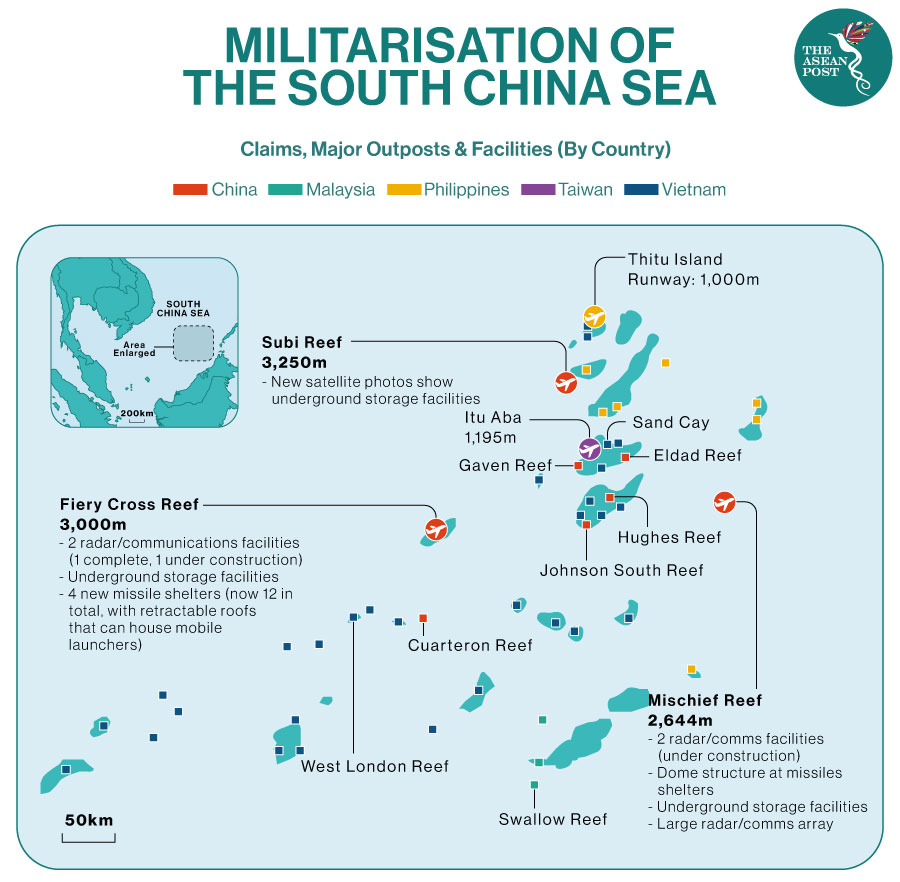

The six-primary claimant-states of the contested waters of the SCS are China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, the Philippines, and Taiwan. Through the years, these states have claimed islands or reefs in the contested waters of the SCS.

For instance, China claims more than 80 percent of the SCS, while Vietnam claims sovereignty over the Paracel Islands and the Spratly Islands. The Philippines on the other hand asserts ownership of the Spratly archipelago and the Scarborough Shoal, which is now occupied and controlled by China, while Brunei and Malaysia claim sovereignty over southern parts of the sea and some of the Spratly Islands as well. Whereas, Indonesia although not a claimant state, asserts an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Natuna Islands on the edge of the South China Sea and has had skirmishes with China related to overfishing in the region.

Likewise, over the years, these claimants have seized control of a raft of sea features, including rocks, islands, and low-tide elevations. For instance, Vietnam occupies between 49 and 51 outposts spread across 27 features in the SCS. These include facilities built on 21 rocks and reefs in the Spratly Islands, along with 14 isolated platforms known as “economic, scientific, and technological service stations,” on six underwater banks to the southeast that Hanoi does not consider part of the disputed island chain, although China and Taiwan do.

In recent years, Vietnam has reclaimed new land on eight of the 10 rocks it occupies and has built many smaller outposts on submerged reefs and banks. Mainland China on the other hand occupies seven. Taiwan occupies one island and shelf including Taiping Island, while Malaysia occupies five, and the Philippines occupies nine. Brunei claims a relatively small area, including islands on Louisa Reef, while Indonesia has a maritime rights claim.

These claimant-states have been involved at some point in time or other in minor naval clashes and skirmishes, usually concerning the forced removal of fishing vessels from claimed territorial waters.

For instance, China and Vietnam had serious military clashes in 1974 and again in 1988 over occupations in the Paracel Island group, while the Philippines and China had a standoff over the Scarborough Shoal in 2012. Just recently, both countries had skirmishes over the Whitsun Reef or otherwise known in the Philippines as the Julian Felipe Reef over an alleged flotilla of more or less 200 Chinese fishing vessels in the reef.

Megaphone Diplomacy

Indeed, for over three months now, disputes between China and the Philippines in the SCS have dominated headlines, and have been the subject of controversies related to certain Philippine government officials and political personalities belonging to the opposition.

The most recent being an act of “megaphone diplomacy” by the Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs whose profanity and expletive-laced tweet called out China over the SCS dispute between the two countries.

“Megaphone diplomacy” refers to making public statements regarding a matter of dispute, which means negotiations between countries or parties are held through social media posts (i.e., Twitter), press releases, and announcements, aiming to force the other party into adopting a desired position.

Locsin is known for his blunt remarks usually posted on his personal Twitter account; odd behaviour for a top Philippine diplomat. He recently tweeted, "China, my friend, how politely can I put it? Let me see… O…GET THE F*CK OUT. What are you doing to our friendship? You. Not us. We're trying. You. You're like an ugly oaf forcing your attentions on a handsome guy who wants to be a friend; not to father a Chinese province."

The President of the Philippines, Rodrigo Roa Duterte somewhat expressed dislike and annoyance over Locsin’s tweet. "China remains to be our benefactor. Just because we have a conflict with China does not mean to say that we have to be rude and disrespectful. We have many things to thank China for the help in the past and its assistance now,” Duterte said during his weekly televised address to the nation on 3 May.

Locsin later apologised but said he was apologising only to Wang Yi, for the sake of his friendship with his Chinese counterpart. “I won’t plead the last provocation as an excuse for losing it; but if Wang Yi is following Twitter, then I’m sorry for hurting his feelings, but his alone,” Locsin tweeted.

China reacted to Locsin’s Twitter outburst by pointing out that the top diplomat of the Philippines should observe "basic etiquette" in diplomacy and shelve megaphone diplomacy. In a statement, China's foreign ministry said, "Facts have repeatedly proved that microphone diplomacy cannot change the facts, but can only undermine mutual trust. It is hoped that relevant people in the Philippines will comply with basic etiquette and their position when making remarks. China has always worked, and will continue to work with the Philippines, to properly resolve differences and advance cooperation through friendly consultations.”

Locsin’s latest tweets are no doubt an exercise in “megaphone diplomacy”, which seems to be at odds with the so-called “bilateral and multilateral quiet/peaceful diplomacy” of the Duterte administration with regards to China over the SCS given the complicated nature of the dispute. It seems that instead of calming the situation to prevent further crisis and escalation in the SCS, Locsin was deliberately fanning the flames to a considerable extent.

The “megaphone diplomacy” of Locsin and certain political personalities without a doubt has produced loud sound bites and political posturing and grandstanding. While it has boosted the sales and readership of media companies, it has not helped in de-escalating, reducing tensions, and achieving the objective of peaceful resolution of the dispute over the SCS between China and the Philippines.

Moving Forward

It is important to ask if megaphone diplomacy being used by the top diplomat of the Philippines is the most appropriate diplomatic strategy to use in addressing the conflict of interests and differences between China and the Philippines.

Truth be told, there is no universal answer to the question. There are times and places when a certain strategy is appropriate, and where it is not. But the complexity of the dispute over the SCS must be the primary consideration when crafting an appropriate diplomatic and peaceful strategy.

On the issues surrounding the disputed SCS, the challenge for the Philippines and even for other claimant-states is to always deploy the most prudent diplomatic approach to achieve the required objective.

In the case of the Philippines, a peaceful and diplomatic resolution of its conflict of interests and differences not only with China but with other claimant states like Vietnam, Malaysia would be the best approach. Filipinos and government officials must have a broader and deeper understanding of the nature and complexities of the dispute, which is a basic prerequisite in crafting a long-lasting solution or approach in resolving the dispute.

Another important consideration, which matters much in the final analysis, is consensus among Filipinos and among those in government in the understanding of the nature of the dispute as well as the appropriate strategy to bring about an enduring solution. This in turn requires a diplomatic approach that is informed by accurate and objective analyses of the historical and contemporary political and economic context, complicities, and complexities surrounding the dispute.

Hence, megaphone diplomacy not rooted in a clear and solid understanding of the complex issues of the SCS dispute would only hurt the trust and mutual understanding already established among claimant-states and may lead to more complications and escalations of tension.

The Philippines in dealing with China and the rest of the claimant-states need not be too loud in its conduct of diplomacy rather it needs to be smarter, mature, constructive, and pragmatic in handling the dispute not only to protect national interests and national security of the country, but also for the mutual benefits of the two countries, to meet the common aspiration of the two peoples (Chinese and Filipinos) towards prosperity, development, and peaceful co-existence as neighbours.

Thus, the use of non-megaphone diplomacy in dealing with very sensitive and complex regional and global issues may bring forth new paths and openings for the Philippines to strike a resolution to its differences and conflict of interests with China and the rest of the claimant-states of the SCS.

This Is Part 1 Of A Series Of Articles On The South China Sea Dispute

Related Articles: