We have arrived at another of those moments, in this pandemic, where it’s critically important that countries respect a central decision-making body rather than go their own way. The issue on the table now is the use of health certificates to regulate international travel.

Sometimes, pandemic decisions need to be made locally to reflect the local context – mask-wearing in schools is an example – but sometimes they really need to be centralised. We saw what can go wrong if they’re not: for example, when, in the absence of a federal policy, states in America ended up bidding against each other for personal protective equipment from China.

International travel is an obvious case where coordination is needed – globally this time. For the world to get back on its feet, families need to be reunited, trade needs to resume and scientists need to travel. We can contemplate this because we have effective vaccines, and some countries have achieved complete coverage of over half of their populations.

At the same time, the Delta variant is tearing around the world, driving a new spike in COVID-19 cases and deaths, and vaccine supply is hugely unequal. In the circumstances, crossing borders needs to be as frictionless as possible – so that all populations are protected but none are discriminated against. Friction will hamper recovery and doubly penalise those countries that are already at the back of the queue for vaccine supplies.

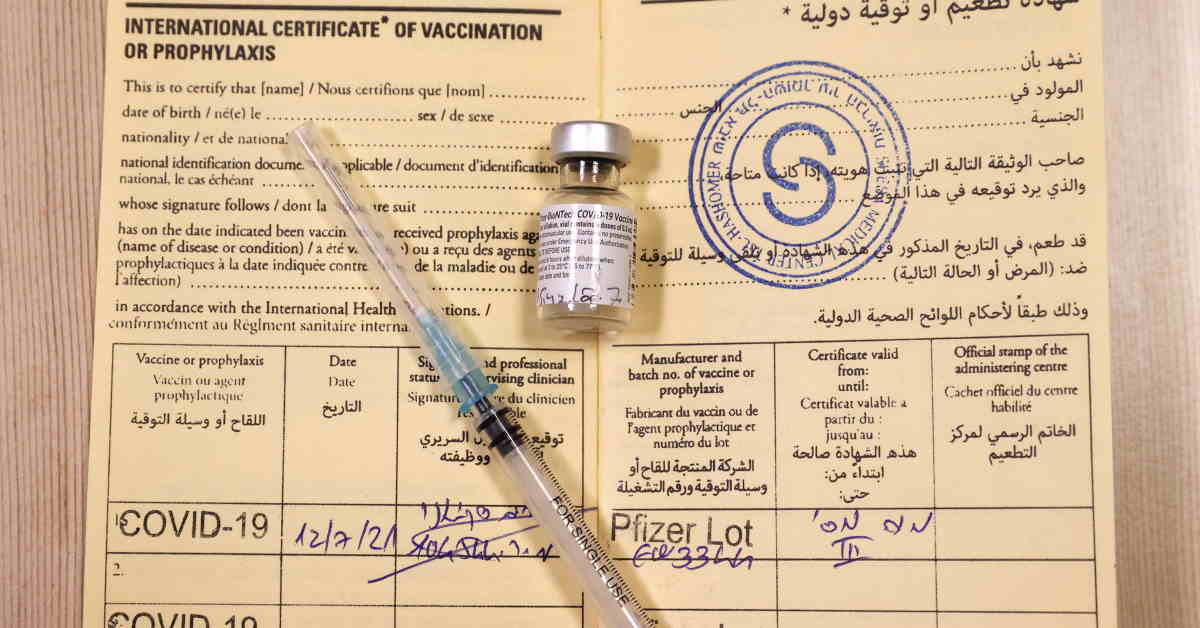

Enter health certificates. Many jurisdictions are putting these in place to control access to all kinds of services, including international travel. With an eye to global equity, the World Health Organization (WHO) has said that a negative viral test or proof of recovery from COVID-19 should be acceptable alternatives to vaccination, when it comes to crossing borders – and it has issued guidance on the use of quarantine in combination with these.

But it also acknowledges that as the vaccine rollout expands, vaccination will become the preferred criterion – and rightly so. Requiring a negative test from all incoming travellers, whether they are vaccinated or not – as is the case in the United States (US) at the moment – creates friction of a different kind, since tests also have to be booked and paid for.

This means jurisdictions urgently need to agree on the vaccines they will accept. At the moment there is no such agreement, only a patchwork of different requirements. Earlier this month we heard about the European Union’s (EU) digital COVID certificate not recognising the India-manufactured version of the AstraZeneca vaccine, Covishield.

But that was just the beginning. Canada accepts Covishield, but not the two Chinese vaccines – made by Sinopharm and Sinovac – that are being rolled out in China and many other countries. In England, meanwhile, the COVID vaccination status service accessed via the NHS app describes itself as “internationally compliant” but doesn’t yet record doses received abroad – even of United Kingdom (UK)-approved vaccines.

This has created headaches for many, including UK-based doctors I have spoken to who have been working on COVID vaccination campaigns in Africa.

There’s an obvious solution to this: all countries should adopt the WHO’s emergency use listing (EUL) of COVID vaccines. Numbering 10 at the latest count, these have met a minimum standard for safety and efficacy. The WHO’s list is the one that many countries build their vaccination strategy upon, if they don’t have their own mechanisms for assessing and approving medical interventions.

Countries that do have such mechanisms – usually the wealthier ones – tend to have approved fewer vaccines to their own national standards. The WHO’s list is the most inclusive, and inclusivity is what’s needed now.

As Marian Wentworth, chief executive of the US-based global non-profit Management Sciences for Health, explains, the decision regarding which vaccines are recognised for travel is fundamentally different from the one about approving a vaccine in the first place. The calculation is not of individual risk, but of the risk an individual poses to another population.

Assuming that a traveller has received a complete course of any EUL-approved vaccine, she will pose a far lower risk to the population at her destination than its own, unvaccinated members. The EUL standard should therefore be sufficient to let her in.

The friction caused by the lack of standardisation on this question takes different forms, of which one is vaccine hesitancy. This is now a major problem in parts of Africa, and though the causes are complex, Wentworth says that many in Africa are wondering – reasonably – why vaccines that are good enough for them are not good enough for Americans or Europeans.

The format any universal health certificate takes also matters. Countries have rushed towards digital solutions; but again, in the interests of inclusivity, some public health experts favour “dumb tech”. This could be the little yellow vaccine book, officially called the International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis, that is issued by the WHO, extra copies of which it is now hurrying to print off.

A paper certificate works even when the electricity is down or you don’t own a smartphone. It’s integrated with existing health information systems and doesn’t raise privacy concerns. The drawback is that it’s easily forged – a risk that is elevated in a pandemic when vaccine supply falls short of demand.

For this reason, some tech organisations have proposed solutions that are a step up from dumb, such as a digitally signed QR sticker that can be attached to a card, and conveys only a person’s identity and their vaccination status.

Covering all bases, the WHO will issue its guidance on digital health certificates in a few days’ time. Countries will then decide whether or not to apply it. They should, because the sooner they do, the sooner we can all get moving again – fairly. – The Guardian