Japan’s success story in implementing the carbon tax and emission trading scheme (ETS) all together can be the best lesson for Indonesia, which its carbon pricing is still up in the air.

The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report illustrates that without immediate, rapid, and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, limiting warming to close to 1.5 degree Celsius (°C) or even 2°C will be beyond reach. This situation definitely raised a red flag on the global climate agenda.

Thus, every nation, especially top GHG global emitters, should speed up their clean energy transition and encourage climate policies as their mitigation plan. One of the climate policies that can be promoted is the carbon pricing instrument.

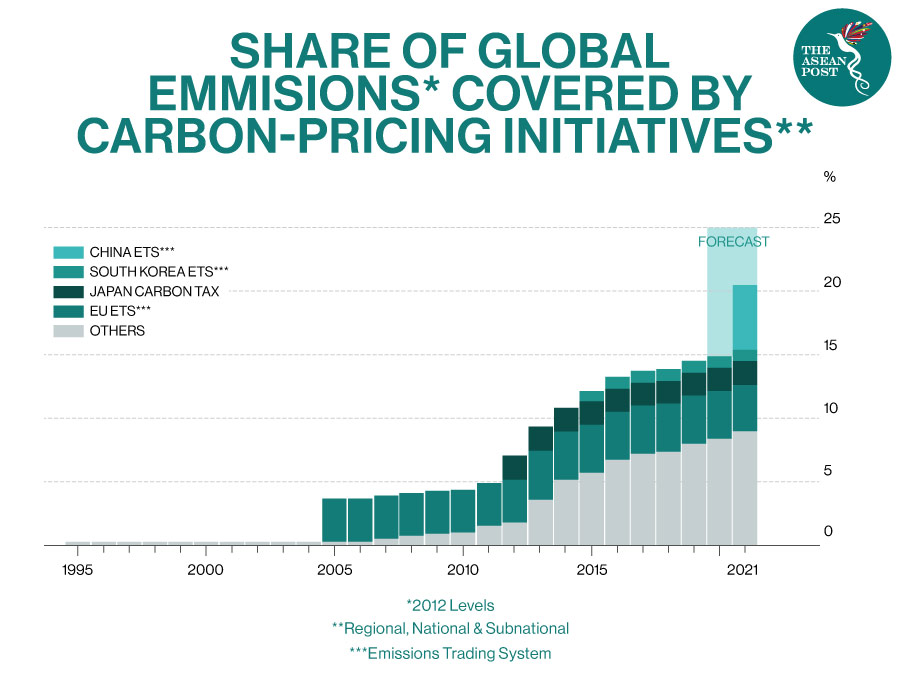

Carbon pricing instrument has been widely used globally in the shape of the carbon tax and ETS. This vital instrument plays a crucial role for every country to achieve its net-zero emission target. The generated revenue is also essential to catalyse clean and sustainable development.

According to the World Bank, 64 carbon pricing instruments are currently implemented since the first introduction in 1990. This number will surely increase along with the commitments made by several other countries. Each country has a different approach to implementing the carbon pricing instrument. Some countries such as Germany, the Republic of Korea, and New Zealand choose ETS. Meanwhile, other countries such as Netherlands, South Africa, and Singapore implement the Carbon Tax.

Interestingly, Japan has concurrently implemented the Carbon Tax and ETS as their climate mitigation plan, and it runs successfully. This success story should trigger Indonesia to replicate what Japan has accomplished.

Japan ETS And Carbon Tax

As the first Asian country that implemented carbon pricing instruments, Japan, through the Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG), started the initiative with carbon dioxide (CO2) cap-and-trade mandatory (or the Tokyo ETS) in 2010. Tokyo ETS targets GHG emissions from commercial and industrial buildings factories, heat suppliers, and other facilities that consume large quantities of fossil fuels.

A year later, the Saitama Prefecture followed Tokyo’s footsteps in introducing ETS, aiming for GHG emissions from buildings and factories. The carbon price set in Tokyo ETS and Saitama ETS is similar despite the different targets. They also give credit to companies who performed outstandingly, and it is essential to mitigate the burden of compliance.

However, unlike Tokyo ETS, Saitama ETS has no penalty when covered sectors fail to meet the reduction targets.

Japan also introduced a carbon tax in 2012 with the price of US$ 2.6/tCO2e (tonnes [t] of CO2 equivalent [e]). This instrument is taxed to all sectors contributing to GHG emissions in Japan, such as industry, building, power sector, and fossil fuels. This carbon tax scheme covers a 75 percent share of Japan’s emissions.

The well-design of Tokyo and Saitama ETS and Japan’s carbon tax has effectively reduced Japan’s GHG emissions. Tokyo ETS successfully cut their GHG emission by 27 percent during 2015-2019. Meanwhile, Saitama ETS contributed to 29 percent of its GHG emission reduction in 2018. Japan also benefitted by generating US$ 2,365 million of revenue from a carbon tax, which is recycled to enhance renewable energy and energy efficiency development.

Japan also realized that the carbon pricing instrument is not the single solution to answer climate change. Japan also needs to introduce supporting policies, such as a fossil fuel subsidies reduction, introducing the environmental tax, also mandate carbon trading plans for automakers. Japan also committed to boosting its renewables’ share of power generation to at least 50 percent.

Japan’s strategic steps are indeed the best example for Indonesia, especially in developing a suitable climate mitigation plan.

What Indonesia Can Learn From Japan

Indonesia should comprehend that ETS and carbon tax can be implemented simultaneously, explicitly targeting the energy-intensive sectors (contributing 36 percent of domestic GHG emissions). Learning from Japan, implementing these instruments must be flexible and encourage cleaner and more efficient energy usage.

However, Indonesia needs to issue a carbon tax first, given that it offers less administrative burden. Then, ETS is followed for a long-term solution.

Indonesia has already planned to introduce the carbon tax, set at IDR 75,000/tCO2e (US$ 5.2/tCO2e). This implementation will generate IDR 32 trillion (US$ 2.2 billion) in additional state revenue and cut emissions by nearly 17 percent. Supposedly, the generated revenue can be recycled to fund green development programs, especially renewable energy and energy efficiency projects.

In fact, carbon tax implementation will shift the market balance. Thus, Indonesia’s carbon tax scheme should be well-designed. Indonesia also has to issue other policies to reduce the impact on the final consumers.

Next, ETS should be promoted for a long-term solution since the cap determines the level of emissions, and the required cuts in emissions cause the price.

ETS needs to be designed to suit local contexts and integrate with other policy priorities in each jurisdiction. Hence, Indonesia can start its ETS from regional jurisdictions that highly contribute to carbon footprint, such as in Java (home to 56 percent of Indonesia's population). Each regional government should also promote incentives for stakeholders who significantly achieved their reduction emission target above the compliance burden.

In addition, other climate policies are vital to combat climate change. Indonesia can replicate Japan on issuing a forestry tax. Also, Indonesia can enhance the strategic partnership with Japan in developing hydrogen energy for a sustainable energy source.

In conclusion, carbon tax and ETS are the two sides of the same coin. They can be powerful in combatting climate change. Learning from Japan, Indonesia can implement both instruments at once. However, those instruments should be well-designed in order not to let them hurt the economy. Furthermore, other climate policies and renewable energy roadmap are essential to optimize GHG emission reduction.

In the end, Indonesia should be committed to its climate mitigation plan to meet both emission reduction and clean energy transition targets.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of The ASEAN Post.