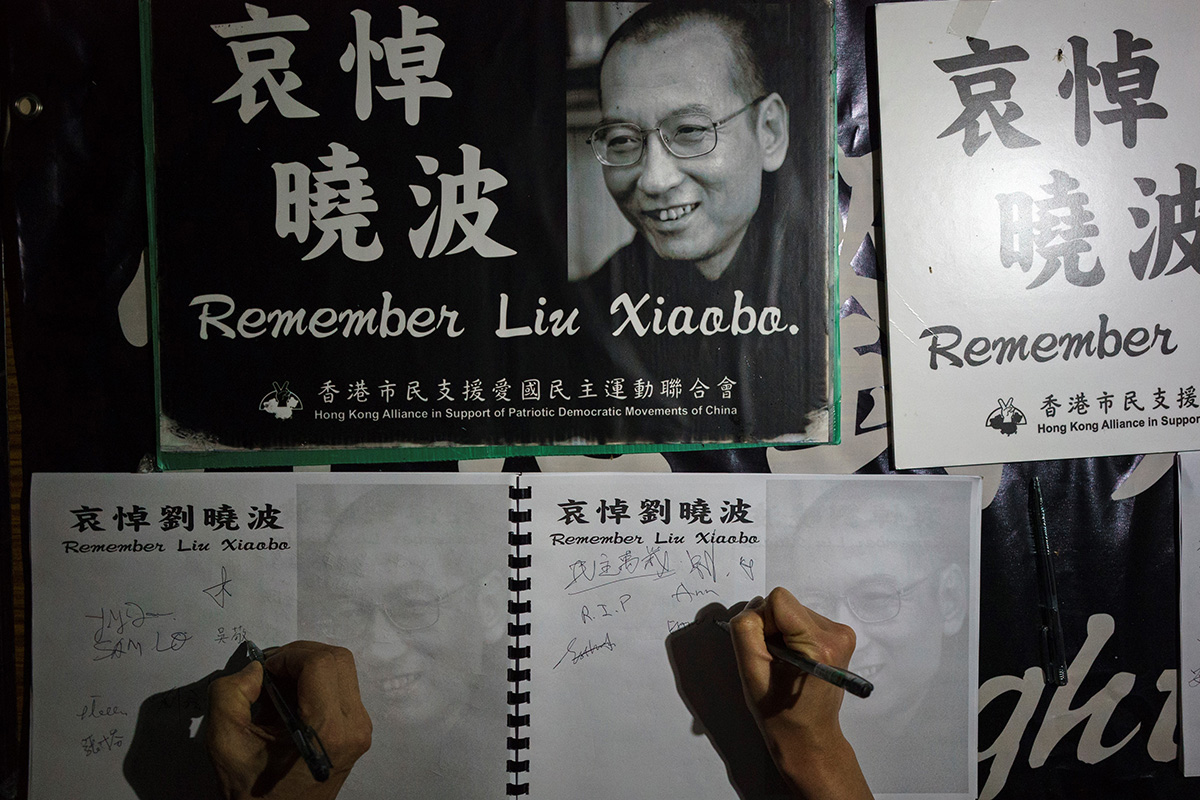

BERLIN - The news that Liu Xiaobo, China's Nobel Peace Prize laureate and most high-profile dissident, was being released on medical parole was chilling news to his many friends and supporters around the world. We all know that the Chinese government releases political prisoners for medical treatment only when their death is imminent. Liu's death on July 13, just days after exchanging a prison cell for a hospital bed, confirmed our worst fears.

Those fears were based on harsh experience. Liu joins a long list of Chinese political prisoners who have died as a result of maltreatment or lack of timely treatment while in detention.

When Li Hong, the former editor of Zhejiang News, was jailed for "inciting state subversion" in 2007, he entered prison in good health. Three years later, he was released on medical parole, a paralysed shadow of his former self. He died shortly afterwards in a hospital bed, surrounded by security officers.

Likewise, the human rights activist Cao Shunli was arrested for "picking quarrels and provoking trouble" in 2013 while on her way to attend a training program in Geneva. She was denied medical care after falling ill in detention and was hospitalized only once she had slipped into a coma. She died a few months later, hooked up to a ventilator.

Two years later, in 2015, the Tibetan monk and community leader Tenzin Delek Rinpoche mysteriously fell ill in prison. The authorities denied him medical parole. After his death, the government refused to release his body for a traditional burial, cremating it instead - without an autopsy.

But Liu's death was different. His fame and stature as an international beacon of hope, freedom, and democracy meant that the Chinese authorities couldn't sweep his fate under the carpet as easily as they had the others. So, while censoring coverage of Liu in the domestic media, they subjected foreign audiences to a macabre pantomime in which a dying man was forced to play the lead role.

Controlling the Narrative

Once medical parole was granted, the despotic regime that sentenced Liu to 11 years in prison in 2009 merely for advocating democratic reform strove to present itself as his merciful protector. Footage was shown of security officers posing as doctors, gathering around Liu's hospital bed to listen to a German and an American doctor tell his wife, Liu Xia, that "the Chinese authorities are very committed to the treatment of your husband." Furious at being used as stooges, the doctors later released a statement: "Liu Xiaobo and his family requested that the remainder of his care be provided in Germany or the United States. While a degree of risk always exists in the movement of any patient, both physicians believe Mr. Liu can be safely transported with appropriate medical evacuation care and support."

The Chinese authorities insisted that Liu was too ill to travel. The truth is that they were never going to grant his wish to die in a free country. His death had to occur under their watch, where he could not use his last breath to denounce them, and where his funeral could not become a stage for condemnations of their oppressive rule.

Indeed, the pantomime continued after Liu's death. At a press briefing two days later, a poker-faced government spokesman announced to Chinese security officers posing as journalists that Liu Xiaobo had been cremated "according to the wishes of the family." Images were shown of a farewell ceremony hastily staged at 6:30 that morning, with Liu's corpse encircled by pots of white chrysanthemums, his wife and siblings lined up on one side, and secret police posing as "good friends" on the other.

In a second press briefing that afternoon, Liu's brother, Liu Xiaoguang, announced that the ashes had been cast out to sea. Footage of a pale green urn being lowered into the Pacific Ocean was shown, with Liu Xia looking down silently from the deck. Liu Xiaoguang expressed his "heartfelt gratitude for the humanistic care of the Party and the government," which, he said, proved the "superiority of China's socialist system." In an effort to explain Liu Xia's absence, the government spokesman explained that she "is enjoying her freedom, but because she has just lost her husband, she is in great sorrow and we would try not to have her disturbed from the outside." Once more, the tyrant's fist was gloved in the velvet of fake compassion.

A clip posted on Twitter revealed the only moments of sanity in this despicable, ghoulish charade. When Liu's brother left the room, a genuine journalist called out: "Where is Liu Xia? Who were all those people in the funeral hall? Were they Liu Xiaobo's friends?" When the press briefing drew to a close, she piped up again: "Can I ask a question? Why are no questions allowed in this press conference? I have many questions! Don't you feel ashamed? The whole world is looking at you." The officials ignored her and left the room in stony silence.

Liu would, no doubt, have admired her courageous search for the truth. He was, after all, a professor of literature at Beijing Normal University. A prolific writer of literary criticism, poetry, and political essays, he was a wild, passionate man with radical opinions and deep convictions. He believed that China had produced only two great intellectuals: the novelist Lu Xun and the economist Zhou Duo. The latter's advocacy of non-violent resistance shaped his world view.

Democracy First

When the pro-democracy movement kicked off in Beijing in 1989, Liu cut short a research trip at Columbia University and returned to China to join the protests. In late May, he met with Zhou Duo in my one-room shack in Beijing and persuaded him to join a hunger strike with the singer-songwriter Hou Dejian and the editor Gao Xin. He hoped that this show of solidarity by four public figures, later dubbed the "Four Gentlemen of Tiananmen," would convince other intellectuals to join the movement.

When the tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square in the early hours of June 4, 1989, Liu was there, weakened by hunger. He grabbed rifles from protesters who were preparing to resist the soldiers' advance and smashed them to pieces; then, with the three other Gentlemen of Tiananmen, he negotiated with the army to allow the several thousand students still in the square to retreat peacefully, avoiding much bloodshed.

In my novel Beijing Coma, the character Shan Bo, closely based on Liu, curses China's premier through a megaphone: "We'll get you in the end, Li Peng! You b-b-bastard! We'll f-f-fight you to the death!" After the massacre, in which unknown numbers lost their lives in the roads surrounding the square, Liu was imprisoned for "instigating counter-revolutionary propaganda," but was released after writing a self-criticism, which he later bitterly regretted. (Afraid for my own safety, I sought refuge in Hong Kong.)

Liu spent the rest of his life in and out of jail, never having a chance to savour true freedom. Even between incarcerations, he lived under constant police surveillance. The deaths in and around Tiananmen Square cast a heavy shadow over his life, and deepened his resolve to struggle peacefully for democracy. In my frequent visits to the mainland after the massacre, I, too, was closely monitored, so we seldom had a chance to meet again and talk.

When I returned to Beijing before the 2008 Olympics, public security officers summoned me for tea at the Great Wall Hotel. The first thing they said was, "Don't meet with any sensitive individuals, especially not Stutterer Liu." A few weeks later, I saw Liu for the last time, in a rushed meeting in a Beijing bookshop. We both knew we were surrounded by secret police, so we didn't dare sit down for a chat.

The following year, after my friend, the activist Ye Du, attended a lecture I gave at Zhongshan University in Guangzhou, an official from the Ministry of Public Security interrogated him, asking whether I had brought a copy of the pro-democracy manifesto Charter 08 for him to sign. At that moment, it became clear to me that Liu was facing another arrest. I spoke to Liu on the phone, and he said he thought he would get three years at the most.

Charter 08, which Liu co-wrote, was based on Charter 77, which had dared to call on Czechoslovakia's Communist government to uphold the international human-rights treaties it had signed. Liu was arrested in December 2008, and his 11-year prison sentence reflected the regime's ruthless accounting: one day for each character of the charter. Many of those who signed, including Gao Yu, Ai Weiwei, Pu Zhiqiang, and Jiang Tianyong, were also jailed. Hu Shigen, Tang Jingling, and Liu Xianwu are still behind bars to this day.

Shortly after Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize - "for his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China" - in October 2010, Liu Xia was placed under house arrest. For eight years, she visited her husband once a month under tight supervision, until the day he was finally wheeled out of prison and into a Shenyang hospital. Throughout all those years, they were never allowed one moment alone together.

Repression and Collaboration

Liu's last imprisonment coincided with China's biggest crackdown on civil liberties - still ongoing - since the Cultural Revolution. Emboldened by their global economic leverage and the compliant silence of the international community, the Chinese authorities remain as intent as ever on curbing free speech and crushing all opposition to their rule. In 2015, more than 300 human-rights lawyers and activists were arrested.

My own books have been banned in China since 1987, but it is only since 2011 that I have been denied the right to return to my homeland. Living in exile, I strive to find ways to express solidarity with compatriots who continue to struggle against tyranny. Last month, on the 28th Anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre (known in China as the "June Fourth Incident"), shortly after beginning a year's residency in Berlin, I painted the numbers 6428 on a Chinese flag and, in the pouring rain, I draped it over the statue of Karl Marx in the city's Mitte district, to honor China's peaceful democrats who have fought against Communist rule. When I learned that Liu was terminally ill, I visited the statue of Carl von Ossietzky, a critic of the Nazis and recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize, who, like Liu, was barred from receiving his prize in person and later died in detention. I gently wiped his bronze face and attached a homemade mask of Liu to draw attention to their shared plight. German children gathered to watch. I handed a girl one of the masks and wondered whether her parents had been born in the former East Germany.

When Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Berlin two weeks ago, ahead of the G20 summit in Hamburg, and presented German Chancellor Angela Merkel with two pandas at the Berlin Zoo, Chinese friends and I donned my Liu masks, stood behind the police cordon and shouted out to the distant zoo entrance gates: "Release Liu Xiaobo! Let him get on a plane to Germany, just like those pandas did!" Under the blazing sun, the police nervously watched our every move, repeatedly requesting that we roll up our large poster of Liu. I wondered why Xi hadn't been taken to the Holocaust Memorial or to see remnants of the Berlin Wall. Are these reminders of Germany's Nazi and Communist past considered less important than a public zoo? Did the citizens of Berlin feel no discomfort in welcoming two pandas to their city instead of the dying dissident Liu Xiaobo?

The next day, a day before the summit opened, a thousand actors covered in clay shuffled silently through the streets of Hamburg to protest against the political apathy and inhumanity of the modern world. As I watched the footage online, I suddenly imagined Liu wandering among them, in striped hospital pajamas, and then being stabbed in the back, crying out, "I have no enemies!" before falling to his death. His assassins are not just the Chinese Communist Party leaders and apparatchiks who slowly murder all opponents in their quest to cling to power. His assassins are also Merkel, US President Donald Trump, British Prime Minister Theresa May, French President Emmanuel Macron, and all the other democratic leaders who are so transfixed by China's wealth that they are prepared to overlook its systematic human-rights abuses. During the entire summit, not one leader took Xi to task over the treatment of Liu Xiaobo. On the day Liu died, Trump hailed Xi as "a great leader," "a good man," and "a terrific guy."

But the Chinese people are also zombie assassins - brainwashed by decades of propaganda and blinded by their recent prosperity. Most believe that dissidents like Liu are dangerous enemies of the state who deserve to rot in jail. China does not lack a Nelson Mandela ready to reconcile its tragic past with a democratic future: in addition to Liu, there have been Wei Jingsheng, Wang Dan, Ding Zilin, Pu Zhiqiang, and others. What China lacks now is a broad movement for change - huge crowds demanding freedom, like those that gathered at the prison gates to celebrate Mandela's release.

For the last eight years, the Chinese authorities sought to muzzle Liu and his wife, Liu Xia, even as they robbed him of his liberty and his dignity. But in the state-enforced silence, the words of his Nobel Prize lecture ring out even louder: "There is no force that can put an end to the human quest for freedom," he wrote. "Freedom of expression is the foundation of human rights, the source of humanity, and the mother of truth."

Liu Xiaobo died as he lived, with courage and integrity. His words will live on, inspiring future generations to continue the struggle for liberty and democracy, and reawakening the world's zombie citizens to join the fight.

(Ma Jian is the author of the novels Beijing Coma, The Noodle-Maker, and The Dark Road. He is currently a visiting fellow at the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) in Berlin.)