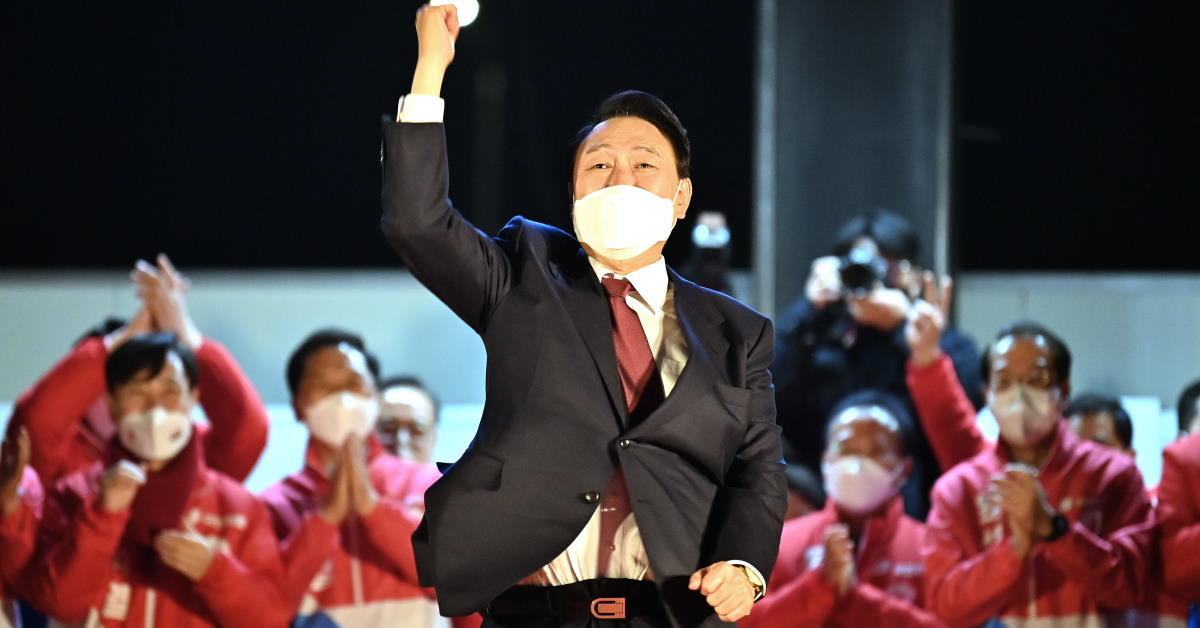

Last month, South Korean voters elected Yoon Seok-youl as their next president. It was a hotly contested race, which Yoon won by a razor-thin margin of just 0.7 percent. What will the conservative People Power Party candidate’s victory mean for South Korea and East Asia?

For starters, Yoon’s government seems poised to shift away from its predecessor’s policy of “strategic ambiguity” in the Sino-American rivalry and restore South Korea’s security and economic ties with both the United States (US) and Japan.

Whereas outgoing President Moon Jae-in’s first official phone call following his 2017 electoral victory was with Chinese President Xi Jinping, Yoon’s first call as president-elect was with US President Joe Biden.

Given that China is its biggest trading partner – larger than the US and Japan combined – South Korea is already a member of the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). The outgoing government has recently declared that it will apply to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), led by Japan and Australia, before the end of its term in mid-May.

In fact, South Korea did not consider joining the CPTPP until after China applied. The actual negotiation for joining will be handled by the new government, which is also expected to join the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, the Biden administration’s proposed vehicle for economic cooperation in the region.

On the domestic front, Yoon will have to confront two immediate economic-policy challenges. The first is soaring housing prices – a key issue in the presidential campaign and a major reason why the candidate representing Moon’s Democratic Party, Lee Jae-myung, lost the election.

The Moon government introduced several policies aimed at stabilising housing prices, including raising property taxes for many homeowners, tightening rules on the reconstruction of apartment units, and introducing stricter requirements for mortgage loans. This demand-focused approach backfired. Homeowners resented the increased taxes; limits on the supply of refurbished apartments drove up prices further; and the housing market tilted heavily toward buyers with cash.

Lee attempted to distance himself from the Moon administration’s failed approach. But it is Yoon who will now have to tackle soaring housing prices with policies focused on increasing supply and reducing government interference in the housing sector, including loosening rules on reconstruction and loans.

The Yoon administration’s second immediate priority will be to address difficult employment issues, including increasing labour-market polarization and a shortage of good jobs for young people. The Moon administration attempted to bolster workers’ economic security by changing fixed or temporary contracts into permanent – virtually tenured – contracts.

It also tightened workplace-safety and environmental regulations, introduced a 52-hour workweek rule for businesses with 50 or more employees, and increased the minimum wage.

But these efforts failed to account for the Korean labour market’s segmentation between overprotected workers at large conglomerates (chaebols) and under-protected workers at small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). In the first segment, firms pursued automation wherever possible, rather than hire more workers with strict working-hour limits and higher wages.

For their part, South Korean SMEs – whose share in the labour market is large, compared to many comparable countries, and which tend to hire more minimum-wage workers – struggled to meet the new requirements, and were even forced to fire workers.

Yoon has pledged that his administration will seek to provide so-called flexicurity, boosting labour-market flexibility and providing a stronger safety net for under-protected workers. But this vision, which emulates the Northern European model, has not been welcomed by Korean labour unions.

Labour-market reform might also help the Yoon administration to address the longer-term challenge of reversing the downward trend of potential and actual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates. South Korea has so far closely followed the Japanese path, with low birth rates and rapid population aging contributing to a one-percentage-point decline in GDP growth every five years.

Japan’s per capita GDP (in purchasing power parity terms) amounted to 70 percent of America’s in the early 2000s – and remained at or below that level for more than two decades. In 2020, Korea reached that level. The question is whether it can continue to grow and avoid Japanese-style “lost decades.”

This will not be easy, not least because one seemingly obvious approach – physical-capital investment – is unlikely to do much good. After all, South Korea’s fixed investment rate, as a share of GDP, is already much higher than that of comparable countries. But Germany – whose per capita GDP amounts to over 80 percent of America’s – has illuminated another way.

Germany’s Hartz labour-market and welfare reforms in the early 2000s went a long way toward increasing potential GDP growth. In South Korea, there is plenty of space to implement similar reforms to boost labour productivity and expand the workforce, especially by bringing in more women.

In 2018, only about 60 percent of Korean women aged 35-39 were in the workforce, compared to about 80 percent in Germany. Overall, South Korea’s female labour-force participation rate is among the lowest in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), followed closely by Japan.

Inadequate labour-market flexibility is one factor driving this low participation. Another is the lack of high-quality, affordable childcare options. In fact, South Korea is the world’s most expensive place to raise a child from birth to age 18, measured as a percentage of per capita GDP.

That is why Yoon has also pledged to improve the provision of social services, from accessible childcare to affordable education to upskilling and retraining opportunities. (Lee proposed cash subsidies.) In Yoon’s view, these welfare policies are also pro-growth policies.

Whether they will be enough to enable South Korea to avoid Japan’s growth trajectory remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: Yoon has his work cut out for him.