In the space of a single day, 28 February, Vladimir Putin’s “Fortress Russia” collapsed. The rouble plunged by about 30 percent, and Russian authorities closed all financial markets. Russians raced to ATM machines to withdraw as much money as they could, desperate to exchange it for anything that wasn’t the rouble. Failing that, they stormed shops to buy whatever they could find before prices skyrocketed.

The flow of news out of Russia was already limited and biased before Putin’s war. Now, it has all but ceased. New censorship laws have made it impossible for independent journalists to work. Most foreign correspondents have left, and the remaining Russian journalists risk 15 years in prison if they share any facts that run counter to the Kremlin’s narrative. Meanwhile, most Russian state websites have been taken down by hackers or closed off from foreigners by the authorities.

Nonetheless, the contours of Russia’s economic disaster are clear to see. In the days following Russia’s invasion on 24 February, a united West responded with sanctions far more severe than those it had imposed after Putin’s annexation of Crimea and incursion into eastern Ukraine in 2014.

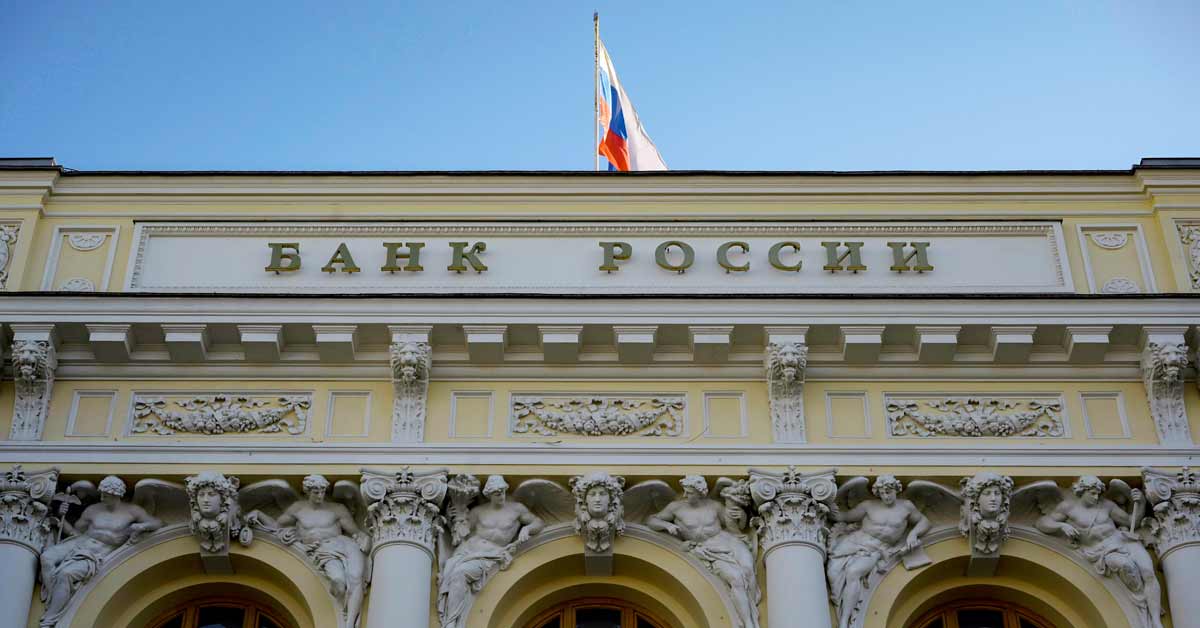

The most important sanctions have been financial. The United States (US) has barred transactions with four of Russia’s biggest state-owned banks; prohibited the trading of Russian sovereign bonds; limited the ability to lend to 13 major Russian companies; blocked key banks from the SWIFT financial messaging system; and, most important, frozen the Russian central bank’s foreign-exchange reserves.

In one fell swoop, Russia has been locked out of international finance. No Westerner will dare interact with Russian financial institutions for the foreseeable future.

Other sanctions have prohibited the export of about half the key technological inputs that Russia buys from US suppliers. And hundreds of Western technology companies – led by Apple – have declared voluntarily that they will stop doing business in, or selling to, Russia.

Other sanctions have singled out Russian elites and their companies. Most of Russia’s top politicians were already subject to sanctions, but now Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Putin himself have been added to the list. Moreover, while top Russian oligarchs have long escaped sanctioning through their extensive contacts in the West, now they find themselves on their own. Their mega-yachts are being seized, and Putin loyalists in Europe are being hunted down like criminals – to the great satisfaction of the Western tabloids.

Sanctions generally introduce three kinds of risks for companies or investors in the sanctioned country. First, there is a risk that the measures, which can be changed with the stroke of a pen, will continue to evolve in unpredictable ways. Second, there is the risk that no one will insure transactions or investments in the sanctioned country. And third, there are reputational risks, and potentially even criminal ones, for any entity that continues to work with the sanctioned regime.

Given these risks, Russia has become too toxic to deal with. Reputable Western companies are not only unwilling to continue buying from or selling to Russia; they also are walking away from sizable investments there. Nearly all the big Western oil companies – BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, Equinor, OMW, and ENI – have declared that they are withdrawing from the country. The only remaining holdout is France’s Total.

Before Putin’s war, Western sanctions on Russia were about 30 percent as severe as those maintained against Iran; yet within just a day, they rose to about 90 percent. The only significant difference was that Russia’s commodity exports were not yet sanctioned. But on 8 March, the US and the European Union (EU) introduced major sanctions on Russian energy.

Russia’s sudden isolation and economic collapse has surprised almost everybody. Having long mocked the 2014 sanctions, Putin and his cronies simply didn’t believe Western governments’ threat of additional “sanctions from hell.” But it is clear that the Kremlin underestimated the West’s sanctioning power. Nobody can claim now that sanctions are ineffective. The only question is whether they will be enforced and sustained.

While the US has persistently advocated harsher sanctions than the EU has, the two are now almost completely on the same page. Most notably, Germany has taken a harder line under its new government – an astounding turnaround that warrants future study.

This united response has been more than sufficient to breach Putin’s supposedly sanctions-proof citadel. Since returning to the presidency in 2012, Putin has largely ignored the need for economic growth and development, focusing instead on amassing some US$630 billion of international currency reserves.

The Russian federal budget has remained more or less balanced, and foreign debt has been kept minimal, at around 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Monetary policy has been strict, and the rouble has had a floating exchange rate.

But the fruits of these policies now lie rotting. The bulk of Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves are frozen, Russian stock markets are closed, and the value of the 31 Russian stocks that are traded in London has plummeted by 98 percent – more than the 94 percent decline in Russian stocks during the 1998 financial crash. All Russian assets have been downgraded to junk status, where they will remain indefinitely. Russia’s capital markets are essentially dead.

Economists predict that the rouble will continue to plummet, approaching a rate of 200 per US dollar by the end of the year (from about 70 roubles before Putin’s war). And on 8 March, the central bank decided to stop exchanging roubles for foreign currencies, which means that the rouble is no longer convertible. A fair guess is that the annual inflation rate will reach at least 50 percent, and that Russian GDP will likely fall by at least 10 percent this year.

Putin might still have his generals, security services, and intellectuals under control. But the Russian economy depends on workers, many of whom are already seeing their inflation-adjusted incomes fall as a result of his pointless war.

Despite Russia’s extreme censorship regime, there was already a major strike in Nizhnekamsk, Tatarstan, over the depreciation of real wages. More social and labour unrest is likely. The disastrous effects of Putin’s foreign and economic policies will be too extreme and far-reaching to hide.