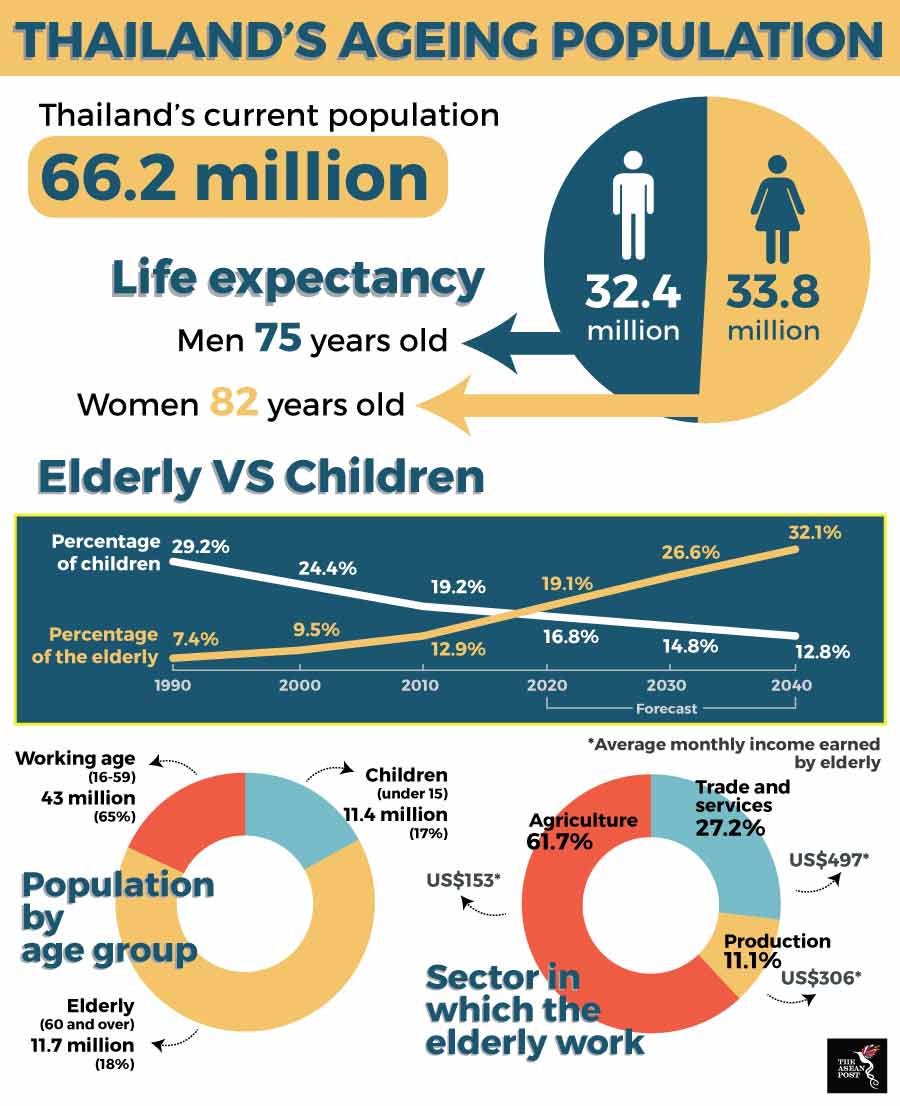

In less than 20 years, almost one in four people – roughly 24 percent of the population – in Thailand would be aged 65 and over, thus making the kingdom a hyper-aged society.

The United Nations (UN) defines an ageing society as one where more than seven percent of the population is older than 65. An aged society has more than 14 percent of the population older than 65, and finally, a hyper-aged society is one where upwards of 20 percent of the population is aged over 65.

Thai society is ageing at breakneck pace compared to other developing nations in the region. While most other countries take almost a century to become an ageing society, Thailand took merely 20 years.

Economic concerns

According to the Thai central bank, an ageing demography is likely to slow down gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 1.5 percent over the course of the next decade. This would be accompanied by an expected decline in labour growth by 3.5 percent annually in the next 10 years down from five percent in the last decade.

Similarly, a continuously ageing populous is set to shave Thailand’s five percent growth rate to 3.5 percent annually if structural problems aren’t addressed immediately. Currently, Thailand’s workforce contributes approximately 1.5 percent to the nation’s GDP growth.

The main reason attributed to a declining workforce is early retirement, as many Thais remove themselves from the labour market from as early as 45 years. Another reason is a shift towards informal workers of which around 20 million are between the ages of 40 and 60 – representing a significant chunk of the 67 million strong population.

Thailand also suffers from worrying birth rate levels. Over the course of half a century or so, the country has seen a sharp contraction in birth rates from six children per woman in 1960 to 1.5 in 2015 according to the World Bank. While most other countries in Southeast Asia have also seen a decline in birth rates since the 1960s, Thailand’s remains the lowest in the region after Singapore. Experts broadly agree that a birth rate of 2.1 percent is necessary to maintain a growing population.

Source: Various sources

Countries with an ageing demography are relatively richer, boasting high income per capita. Singapore, for instance is home to an ageing yet affluent society with a per capita annual income of US$57,714 according to 2017 figures from the World Bank.

Thailand’s per capita annual income on the other hand stands at US$5,720 indicating that Thais are ageing faster than they are accumulating wealth. Nevertheless, some Thais still work after retirement mostly in the agricultural sector. However, their average annual income is a meagre US$1,836 and many are also reliant on state welfare to cover sustenance and increased medical costs.

In the long term, this will place pressure on the state’s welfare system. Given a declining workforce, this will also reduce the national pension pool leading to a downward spiral of an increasingly ageing and poorer society.

Possible solutions

Before widening the social security safety net, the government of Thailand must first address the core issue of dwindling birth rates and enact pro-family policies. Already, three tax breaks aimed at encouraging couples to have more than one child are in place. However, more needs to be done in terms of providing effective childcare policies to lure couples into building larger families like free nursery facilities, affordable healthcare for children and affordable preschool education.

In the shorter to medium term, the government must look into reskilling the workforce to adopt a more “lifelong learning” approach. Besides that, private companies must also play their part in increasing workplace flexibility and providing other employment perks like increased annual leave and more attractive bonuses to further boost workforce productivity.

On a macro level, the Thai government could adopt the Chinese model of implementing structural shifts towards higher value manufacturing and leave lower-value production to ASEAN’s frontier markets. Accordingly, the country’s future workforce must be trained in the skills required for higher value-add jobs which will help boost labour productivity levels.

Thailand’s ageing demography is a growing concern, which, if not handled properly could deal long-term structural blows to the economy of the kingdom. Now more than ever, it should be high up on the priority list for the government to address.

Related articles

Can an ageing ASEAN stay competitive?