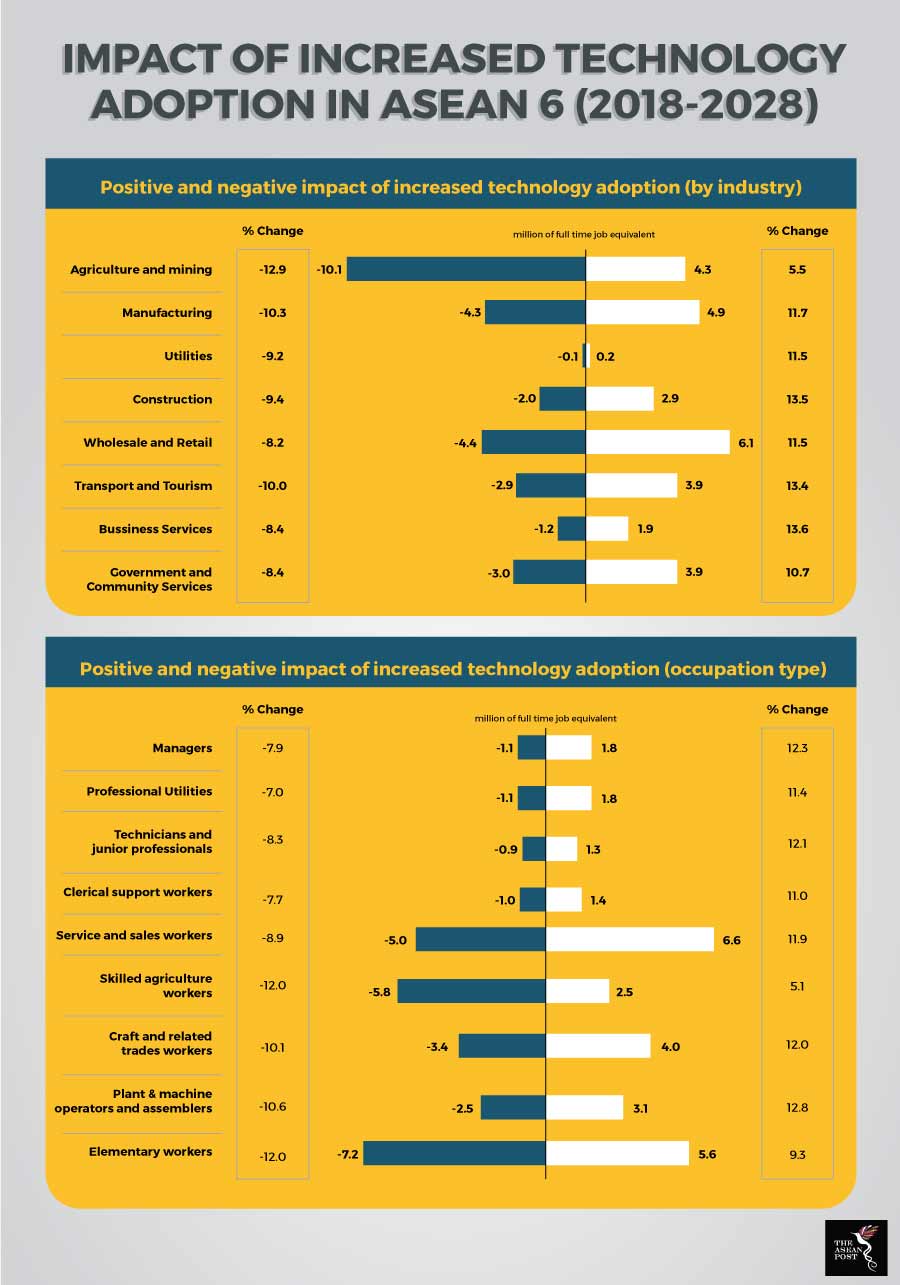

Thanks to digital transformation and the Fourth Industrial Revolution, it is possible for the same output from ASEAN's top six economies today to be produced using 28 million fewer workers by 2028.

Digital transformation is always said to disrupt the workforce but its impact has never been truly quantified. Network vendor Cisco has decided to fix this situation by commissioning a study with Oxford Economics.

The report, Technology and the Future of ASEAN Jobs, forecasts how artificial intelligence (AI) in software, hardware and robotics will change the employment landscape among ASEAN’s six largest economies (ASEAN 6) by 2028.

Agriculture will be the hardest hit, where there is expected to be 6.6 million redundancies by 2028. Demand for skilled agricultural workers and elementary workers or labourers will drop, as these jobs can be replicated with the use of technology.

However, productivity gains from technology adoption will also reduce prices and drive growth, which in turn will create new demand for workers in other sectors such as wholesale and retail, manufacturing, construction and transport. An expected increase in retail spending will create job demand in wholesale and retail. However, these jobs will be more tech-driven as floor sales, check-out counter and warehouse staff will no longer be required.

Source: Cisco, Oxford Economics

Source: Cisco, Oxford Economics

As the labour market evolves, the required skillsets will change as well. The study said 41 percent of the 6.6 million redundancies “acutely lack” the IT skills required by new jobs. Almost 30 percent lack the “interactive skills” demanded by future vacancies, such as negotiation, persuasion and customer service skills. Just over 25 percent lack “foundational skills” such as active learning, reading and writing skills.

Policy change required

To mitigate this, ASEAN 6 countries may have to make massive policy changes to their education systems. Government departments, businesses, educational institutions, technology providers and workers’ groups need to work collectively to equip workers with the necessary tools and skill sets for the transition.

Kiran Karunakaran, a partner at consultancy firm, Delta Partners, wrote that the adoption of AI is guided by trust and risk. Low-hanging applications are adopted rapidly because they can lead to increased revenue and higher customer loyalty and even if the recommendation is incorrect, it does not lead to short-term commercial risk.

As AI becomes increasingly sophisticated, more applications will adopt it. This will affect industries where the level of skills required can be easily machine-learned to improve cost and productivity. In countries where technology adoption is rapid, jobs in contact centres or Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) may be at risk. “The Philippines is probably the market that will feel the effects of this the most, followed by Thailand and to some extent, Indonesia,” he said.

The pace of AI adoption should be managed through a balance of regulation, policy and enablement. “If not, whole industries run the risk of being disrupted and the social implications could be dire,” he added.

“Machine learning technologies are particularly equipped to solve complex optimisation issues. In these situations, the upside far outweighs the risk of social displacement,” he explained. Governments should drive AI adoption in energy distribution, healthcare systems and food production.

Singapore is estimated to have 500,000 jobs displaced by 2028 due to its digital transformation. Although a seemingly small number, it represents almost 21 percent of its workforce. By comparison, other ASEAN 6 nations’ job displacement is caused primarily by playing catch-up and adopting existing technology.

Vietnam and Thailand are expected to have 7.5 million and 4.9 million job displacements by 2028, which represent 13.8 and 11.9 percent of their workforce, respectively. A large number of these jobs are monotonous and classified as low-productivity, mostly in agriculture.

Job displacement in Indonesia and the Philippines will be lower in terms of percentage of workforce. This is due to the abundance of cheap labour in these markets, making it harder for technology adoption to show cost savings benefits.

In Cambodia, where the textiles, clothing and footwear (TCF) sector represents about 90 percent of its manufactured exports, automation threatens over 600,000 jobs. The low wages and relatively unstructured nature of the work currently limits the extent of automation and technological disruptions, said Foo Suan Yong, senior expert at the ASEAN+3 Macroeconomic Research Office Limited (AMRO). “But graduation from basic automation to advanced AI will surely come, and developing economies have limited time to adapt,” he said.

In developing economies, employment traditionally shifted out of low-value agricultural jobs into low-value manufacturing jobs. This would be a stepping stone to higher-value jobs in the production and services sector as the economy develops.

However, the report painted a scenario where only 40 percent of new jobs will be created in the manufacturing sector in the coming decade, while the rest will appear in services. Developing ASEAN economies will find themselves having to leapfrog the manufacturing phase and moving to services in order to keep up with the rapid changes in job demand.

Related articles:

Education in the Age of Automation

Thai jobs on the line if the country fails to adapt to new technologies