The University of Thai Chamber of Commerce (UTCC) recently revealed that the slowing economy has triggered a surge in household debt of 7.4 percent this year. The university's latest survey of 1,201 respondents during 11 to 23 November found that household debt averaged 340,053 baht (US$11,248) per household, compared with a year-earlier at 316,623 baht (US$10,473), which was up 5.8 percent from November 2017.

"This is particularly fuelled by the domestic economic slowdown, which is affected by the prolonged trade war, lower exports and tourism. Even worse is that farm prices remain relatively low as expenses increase," Thanavath Phonvichai, vice-president for research at the UTCC, was quoted by local Thai media as saying.

The university’s survey found that household debt stems from borrowing for general spending, car and housing loans, credit card charges and existing debt repayments.

One of the key findings, however, was that while some 59.2 percent of the debt was formal debt borrowed from legitimate financial institutions, 40.8 percent was what was considered underground debt, meaning debt owed to loan sharks.

Loan sharks is a major problem in Thailand – as it is in many other places around the globe. In September 2018, it was reported that the then-military government – through its efforts to help those who had fallen victim to loan sharks – had succeeded in returning land and assets worth 3.25 billion baht (US$107.5 million) to borrowers in the Northeast. The Northeast is one of the poorest regions in the country.

At a ceremony in Kalasin, then-Thailand Deputy Prime Minister, Prawit Wongsuwon, who also served as defence minister, handed 1,407 title deeds covering more than 5,100 rai to residents in eight north-eastern provinces. (One rai is a unit of area equal to 1,600 square metres).

While the government deserves recognition for the amount returned to borrowers, the amount returned also paints a picture of how big an issue loan sharks are in the Southeast Asian country. Just this year, in February, Thai police arrested 14 loan sharks in Bangkok for lending money at rates of up to 20 percent per day.

Inequality

Loan sharks have long been an issue in Thailand. In October 2014, local news media agency, The Nation published an opinion piece in which it said a toxic mix of inequality and lax financial discipline were among the chief reasons why many citizens fall prey to illegal lenders.

It would be unfair to state here that Thailand has not made efforts to address inequality in the country. There has been real improvement in the past few years. However, the fact of the matter is that inequality continues to exist.

In October, The ASEAN Post published an article titled, “Growing gap between richest and poorest Thais”. In that article, it was noted that the Bank of Thailand’s research institute, the Puey Ungphakorn Institute for Economic Research, found that approximately 36 percent of Thailand’s corporate equity is held by just 500 individuals compared to the country’s current population of about 69,625,582 people. The institute’s report states that each of these 500 individuals amass some 3.1 billion baht (US$102 million) per year in company profits. This is compared to the average yearly household income of around US$10,000.

It has long been known that only one percent (known as the one percenters) own most of the world’s wealth. This is certainly the case throughout most of the world; the ASEAN region being no different. Nonetheless, in the case of Thailand, this wealth inequality is simply higher.

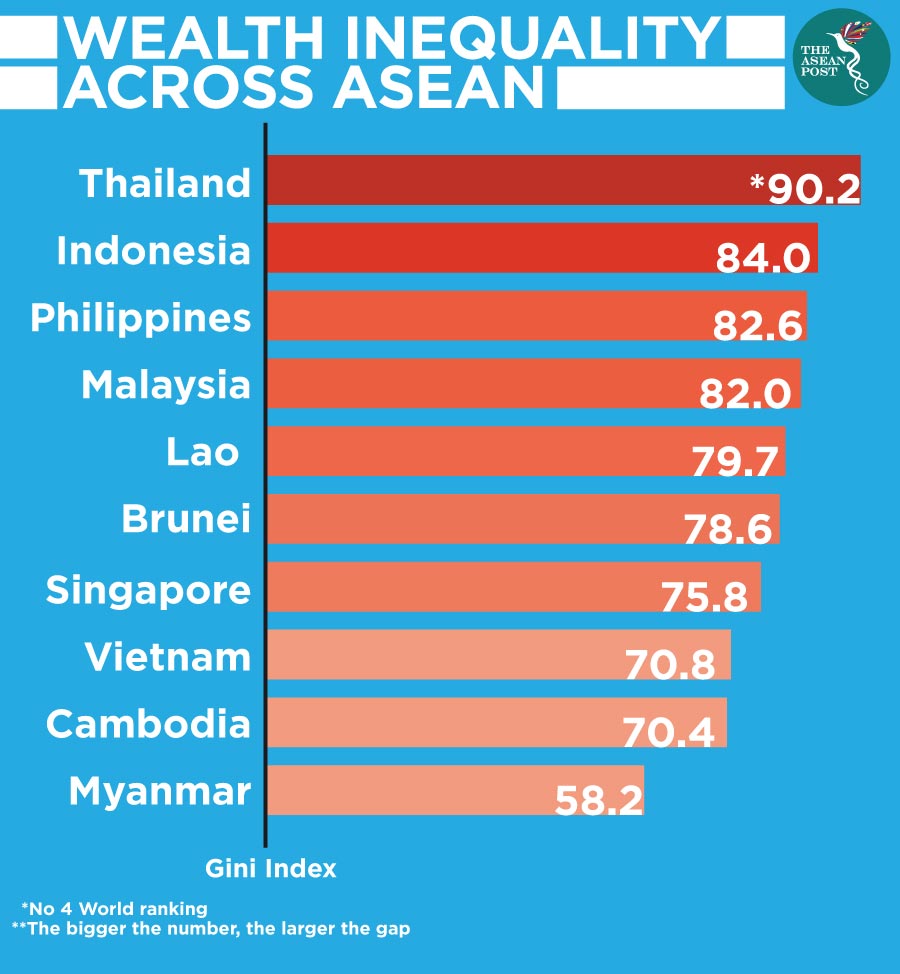

A report published at the turn of the year by the Credit Suisse Research Institute titled, “The Global Wealth Report 2018”, showed Thailand scoring 90.2 on the Gini index. This made it the country with the widest income inequality in ASEAN and one of the four worst performers on a world chart which included Ukraine (95.5), Kazakhstan (95.2), and Egypt (90.9).

The Gini index is a simple measure of the distribution of income across income percentiles in a population. A higher Gini index indicates greater inequality, with high income individuals receiving much larger percentages of the total income of the population.

Thailand’s slowing economy may further exasperate issues of inequality and, in effect, the problem of loan sharks. As Thanavath was quoted as saying, the slowing economy has curbed people's income, prompting them to rely more on loans for daily spending.

"The government should come up with more stimulus measures to accelerate recovery by the middle of the first quarter next year. If the economic recovery fails to manifest by then, a surge in household debt is anticipated next year," he said.

Related articles: