ASEAN countries should do more to promote their cuisine globally via gastrodiplomacy and tap into the vast potential it offers.

The practice of promoting a country’s identity, heritage and diversity overseas through its cuisine or “gastrodiplomacy” is an increasingly popular government strategy for diplomacy and branding and can serve several purposes.

Its best definition can perhaps be provided by the International Institute of Gastronomy, Culture, Arts and Tourism, an international non-profit organisation based in Spain which calls gastrodiplomacy “a new form of public strategy, with state encouragement for dissemination of its cuisine at official events (and) international fairs or support financing its restaurants around the world.”

Globally, the rise of the middle class and globalisation has seen more people with disposable incomes eager to explore new tastes, and the spread of restaurants serving authentic cuisine provides locals with an “exotic” cuisine without the need to travel to a country to experience it.

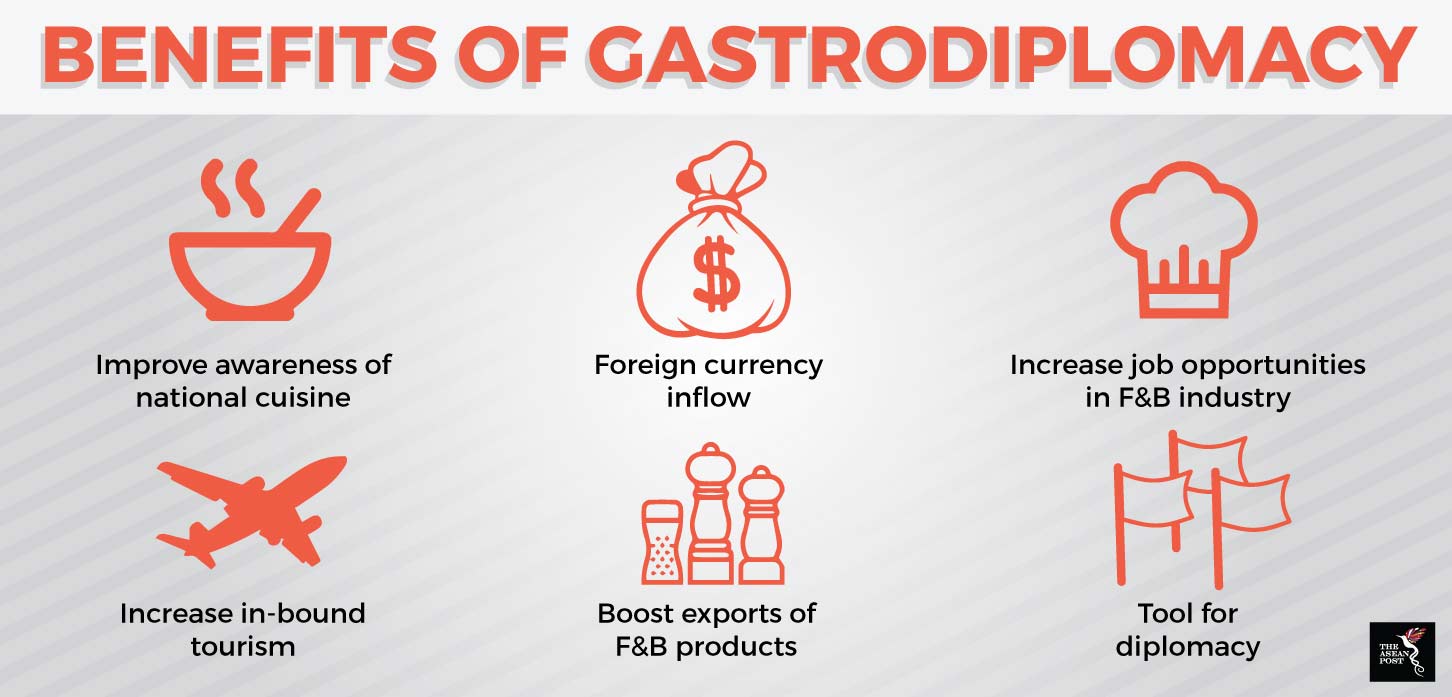

Apart from improving awareness of national cuisines and the cultures surrounding them, gastrodiplomacy also helps create more opportunities in the food and beverage (F&B) industry – both in the host country and the country which is importing its talent, especially as chefs.

From an economic perspective, it boosts exports of F&B products – such as spices and herbs – needed to make distinctive national dishes. In addition, new markets open up for pre-packed sauces and ready to eat meals for those who develop a taste for a particular cuisine and want to try preparing it in their homes.

Tourism also receives an indirect boost from gastrodiplomacy, especially in countries which offer a diverse range of food offerings which differ from state to state.

Gastrodiplomacy in Southeast Asia

Thailand and Malaysia are the only Southeast Asian countries which have made concerted efforts to promote gastrodiplomacy.

Thailand provides a shining example of gastrodiplomacy at its best with its pioneering Global Thai campaign introduced in 2002.

In the United States (US), the number of Thai restaurants has grown from around 500 in 1990 to more than 5,000 now. Globally, the number is estimated to stand at 15,000.

A well-coordinated joint effort by various Thai government agencies has been paramount to the blossoming and success of Thai restaurants around the world.

Thailand’s Department of Export Promotion provided prototypes for three different “master restaurants” which offer set aesthetics and menus – making it easier for investors to get their foot in the restaurant business. The same department set up meetings between Thai and foreign business people, conducts market research on local tastes and trains chefs at foreign restaurants.

Meanwhile, the Export-Import Bank of Thailand and the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Bank of Thailand offers loans to Thais wishing to open restaurants abroad and the Public Health Ministry’s Manual for Thai Chefs Going Abroad provides information about recruitment, training, and local tastes.

Malaysia kicked off its Malaysia Kitchen for the World campaign in 2010 to promote Malaysian cuisine and recipes globally, with a strong focus on US and United Kingdom (UK) markets.

Spearheaded by Malaysia’s trade commission or MATRADE, the campaign hired celebrity chefs from Malaysia and abroad to appear in various television programmes to extol Malaysian cuisine. Malaysian celebrity chefs entertained and enthralled visitors at food fairs, and there were also showcases and cooking demonstrations at famous landmarks such as London’s Trafalgar Square.

In New York, the campaign organised a Malaysian Restaurant Week where 20 Malaysian restaurants in New York City, New Jersey and Connecticut offered three-course fixed price menus hoping to put the cuisine on par with other popular cuisines in the New York metropolitan area.

Asian examples

Many countries in Asia have invested heavily in gastrodiplomacy.

South Korea’s Korean Cuisine to the World campaign was a US$77 million initiative launched in 2009 which aimed at quadrupling the number of Korean restaurants overseas and establishing Korean food as a major global cuisine by 2017, according to the University of Southern California’s Centre on Pubic Diplomacy.

Taiwan’s All in Good Taste: Savour the Flavours of Taiwan campaign was launched in 2010. US$34.2 million was invested by Taiwan over four years in an effort to raise the country’s international brand, including its culinary, cultural and commercial offerings.

In 2008, non-profit organisation Japanese Restaurants Overseas opened offices in Bangkok, Shanghai, Taipei, Amsterdam, London, Los Angeles and Paris. Soon after, Japan established a cooking school in the UK, held seminars in London and Paris and sponsored Japanese chefs to attend cooking schools and workshops all over the world.

What can ASEAN do?

Although there are region-wide initiatives to promote national cuisines such as ASEAN’s Joint Declaration on Gastronomy Tourism which was adopted by ASEAN’s tourism ministers in January 2018, its efforts are centred on bringing in tourists by using national cuisines as a pull-factor.

The first ASEAN Gastronomy Forum which will be held in Thailand from 21-22 March is the perfect platform for regional leaders to discuss gastrodiplomacy and how the region, which offers a diverse range of foods and dishes, can capitalise on it.

With Thailand chairing ASEAN this year and bolstered by their success in launching Global Thai, gastrodiplomacy and its value as both, a soft-power instrument for boosting a country’s public image and as an economic tool should be on top of the agenda in Bangkok.

Related articles:

China’s soft ambitions for the world

Large restaurant chains adopt new technologies to increase productivity