Dense housing settlements and high-rise blockades without sight of green is one of the disadvantages of urbanisation. While urban living continues to offer many opportunities such as jobs and services, urban green is a vital component in any urban ecosystem. Urban green spaces include parks, fields, gardens, urban forests and wetlands providing ecosystem services, including climate regulation, food and opportunities for recreation.

The 2018 ASEAN Sustainable Urbanisation Strategy (ASUS) report showed that the resource footprint of the region’s cities is expanding. The annual growth of ASEAN’s urban population grew by around three percent annually, but the rate of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have increased by 6.1 percent.

Many ASEAN cities are also among the world’s cities most exposed to natural disasters and environmental concerns, particularly from rising sea levels as a result of climate change. And rapid urbanisation is only exacerbating the risk of these disasters. Compromised ecosystems significantly upset the livelihoods and food security of local communities.

Southeast Asia has the highest urban ambient air pollution levels worldwide with an annual mean level often exceeding five to 10 times the World Health Organization’s (WHO) limits.

Nonetheless, Southeast Asia continues to build. Open spaces and old buildings are making way for expressways, modern offices and apartment towers to accommodate ever-growing populations while magnifying the harmful effects of the urban sprawl.

According to the WHO, green urban areas facilitate physical activity and relaxation; a lack of which has contributed to an estimated 3.3 percent of global deaths. Green spaces in cities are beneficial for human well-being.

Threat to green lungs

Green spaces within an urban environment can counter-balance the urban sprawl. They provide oxygen to densely populated cities, like lungs. Trees can capture a number of greenhouse gases (GHG), prevent erosion and help in drainage. Urban green spaces grant residents a reprieve from air, noise and visual pollution, as well as help cool down surrounding developed areas.

Parks and green spaces have a role to play in cities. Some ASEAN cities have initiatives in place to expand their green spaces.

Taman Rimba Kiara, Malaysia’s most important city centre green lung’s existence is at stake with many unresolved issues.

Situated at the edge of the capital city Kuala Lumpur, it is a designated public park under the Kuala Lumpur City Draft Plan 2020. In 2016, a RM3 billion (US$725 million) development project was proposed on the site, which local residents rallied against. In recent news, the Malaysian government has claimed that it has managed to reduce the development area while keeping most of the park untouched.

The Makkasan area in central Bangkok stands in stark contrast against the Thai capital’s skyline of high-rise buildings. “It is the last big space we have in Bangkok, and our last opportunity to create a big green space for the people,” said Pongwan Lassus, its architect and designer.

The fate of urban green spaces is often left to communities and conservationists pitting their meagre resources against wealthy developers and powerful authorities. Finding ways to reclaim land and promote green spaces is hard but essential to the quality of life.

Man-made parks

Recent developments have seen the incorporation of green spaces but the overall impact remains modest in most cases.

In 2018, a community of 300 or more people living next to an old fort in Bangkok were evicted and their traditional wooden buildings razed to make way for a public park, that critics say is meant only to impress tourists.

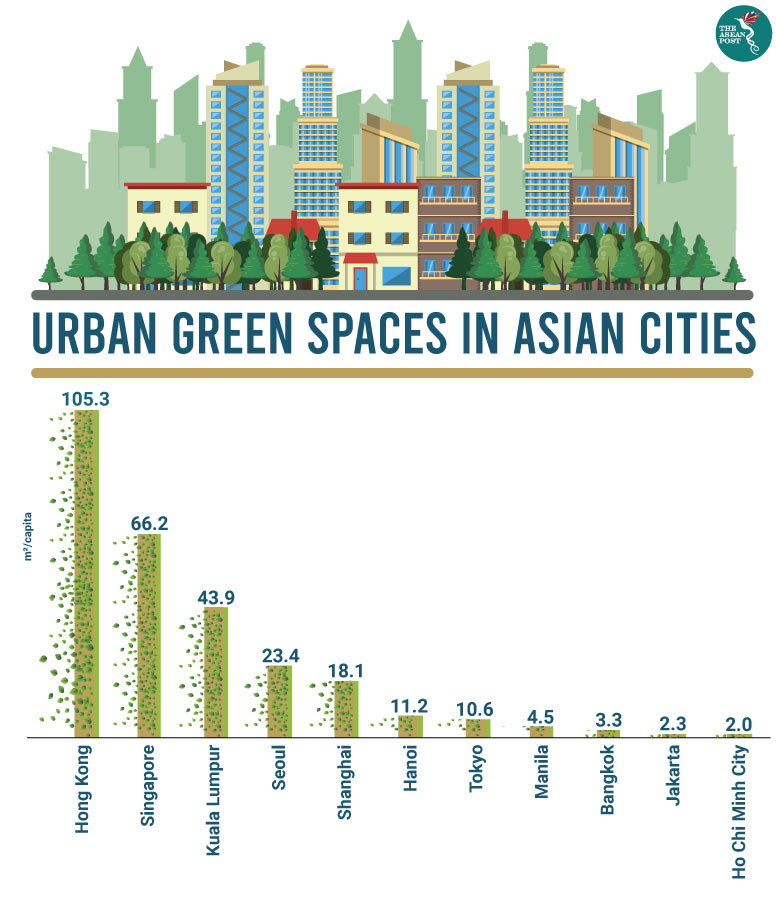

The same, however, cannot be said of Singapore’s ‘City in the Garden’, which has acquired a special significance and is regarded as an economic, social and environmental asset to the country. The park has the highest urban tree density which is impressive considering the fact that almost 30 percent of the island state’s urban areas are covered by greenery. The park also contributes to the national identity, health and welfare of the population.

Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City currently lag behind most other large Asian cities in terms of green space. According to a 2018 Solidiance report, Ho Chi Minh City is focusing on developing green spaces within residential projects and new urban developments. The city is also protecting a 150-hectare existing forested area.

Hanoi, on the other hand, intends to increase the number of trees and water features by 2030. The city plans to increase the number of urban green spaces around apartment buildings which will account for eight to 10 percent of land area.

As countries in ASEAN continue to develop, perhaps it is time to consciously plan to include more green spaces in cities to provide beneficial effects to their respective populations.

Related articles: