There’s been much hype and agitation and, by extension, circulation of kopitiam (coffee shop) talk about reports of Malaysia falling behind its regional counterparts and peers in terms of foreign direction investment (FDI) which include losing out on key strategic investments so that the country now (yet again) is supposed to be down on that path towards becoming a failed state (which we’ve heard many times before).

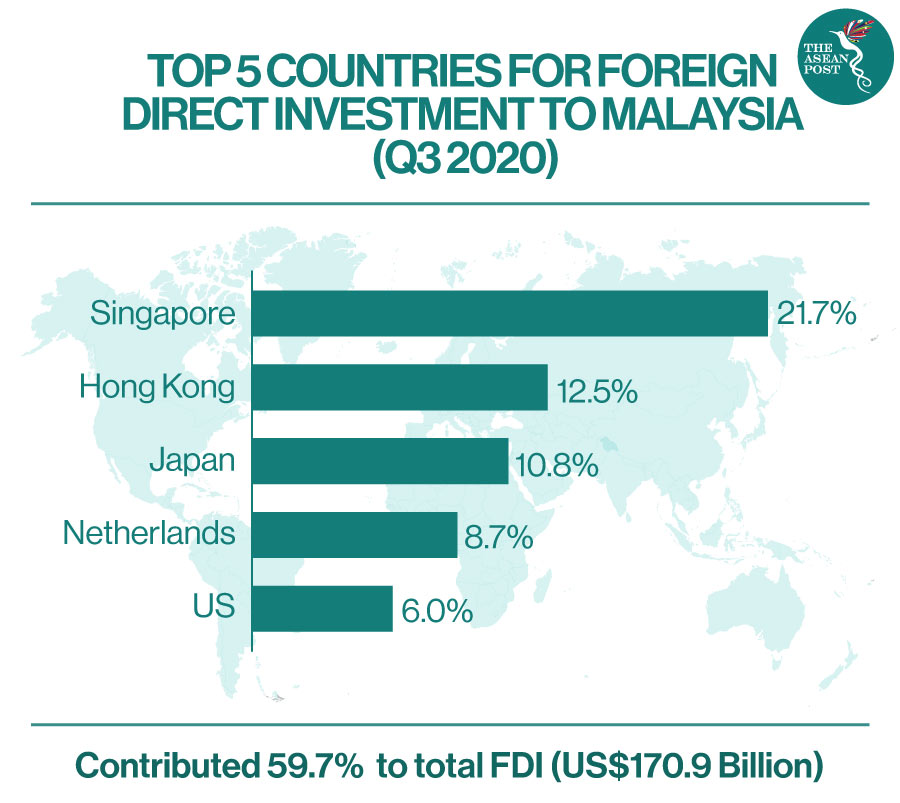

Such a grim outlook could be justified on the basis that according to a United Nations Conference on Trade & Development (UNCTAD) report, “Investment flows to developing countries in Asia could fall up to 45 percent in 2020”. The report also highlighted that Indonesia, Singapore and Vietnam received more than 80 percent of the US$156 billion in FDI that ASEAN countries pulled in last year. Only five percent or just US$7.8 billion went to Malaysia – which of course doesn’t seem to augur well for the country.

Some of the specific examples making the rounds in social media and messaging apps include: (1) Samsung Electronics is intending to shift its display production operations from China to Vietnam – but which has actually been officially denied by the company itself. For the record, Samsung already has six factories and two research and development (R&D) centres in Vietnam; (2) Apple through its manufacturing partner, Foxconn, is moving only some (i.e., not wholesale) of its iPad and MacBook assembly lines to Vietnam from China as part of a “parallel supply chain” strategy. This means that there’s scope for other regional countries such as Malaysia to attract the rest of this production network in the global value chain (GVC); (3) Tesla is building a factory in Indonesia and even contemplating a SpaceX launchpad too – when in reality talks between the electric vehicle and clean energy company with the Indonesian government is still on-going; (4) Amazon is investing US$2.8 billion to build a localised data centre (Amazon Web Services/AWS Region consisting of inter-connected clusters known as Availability Zones) for its cloud computing services in West Java, Indonesia. Data localisation would also minimise the potential for aggressive tax avoidance (transfer pricing) for companies such as Amazon. But should Indonesia decide to go ahead and join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the advantages gained from data localisation will be diluted. This is because the CPTPP has an in-built bias against data localisation and corresponding tax implications alongside intellectual property rights (IPR); and (5) Alibaba, Bytedance, Tencent, etc., are setting-up their regional headquarters in Singapore. This has no bearing at all on the investment in Malaysia’s digitalisation drive, including assimilation of 5G technology, among others. It should be recalled that Alibaba had co-invested in the establishment of what is the world’s first Digital Free Trade Zone (DFTZ) in Malaysia.

Nonetheless, this doesn’t mean that Malaysia should become complacent and rest on its laurels.

In the context of the on-going COVID-19 pandemic, we are seeing the acceleration of international and regional cooperation (especially the latter) where COVID-19 affects the whole spectrum of trade and investment linkages such as the supply chain in vaccine procurement and manufacturing, the growth of e-commerce as well as supply chain reconfiguration brought about by reshoring, onshoring, etc.

Dependence On China

The solution, therefore, isn’t to be overly dependent on China; something that can “reproduce” the kind of ramifications and unravelling analogous to the “dependency theory” (which basically stipulates that Malaysia as a periphery nation ends up losing its resources to China as the core nation) but further intensifies the diversification of its supply chain lines.

Other policy measures to ramp up efforts in the face of friendly (and complementary) rivalry from regional competitors would be as follows – based on the counter-logic that Malaysia shouldn’t be overly reliant on FDI:

Firstly, the country must increase its domestic direct investment (DDI) and strengthen the small & medium-sized enterprises (SME) base.

A new policy vision is called for in which the existing policy paradigm is turned on its head with SMEs at the forefront as catalysts of economic and employment growth. It would also benefit the government-linked companies (GLCs) and foreign investors as the spill-over effect is reversed.

One of the ways is to boost and strengthen SME linkages and production networks in ASEAN – thus enabling SMEs to contribute towards intra-ASEAN trade and investment flows as well as regional integration. This could be done through the pre-existing ASEAN Inclusive Business Framework within the broader structure of the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC).

Furthermore, SMEs in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia should enhance cooperation and involvement. For example, in the Indonesia-Malaysia-Thailand Growth Triangle (IMT-GT) and the Singapore-Johor-Riau Growth Triangle (SIJORI).

Secondly, strengthening regional cooperation through ASEAN and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) for greater regional inter-dependency.

There should be an ASEAN Industrial and Economic Masterplan (paralleling the ASEAN Connectivity Masterplan 2025, for example) that apportions and designates production network and supply chain bases along the competitive edges and advantages and strategic locations of member states; for example, Vietnam’s manufacturing lines and zones for electrical & electronic (E&E) products are fully integrated with Malaysia’s.

Other policy steps would include the resuscitation of cross-border listings such as the ASEAN Trading Link (set up in 2012) by building upon the ASEAN Capital Markets Forum (ACMF) for cross-border offerings of collective investment schemes (CIS).

The revival of the Central Limit Order Book (CLOB) that was banned without any prior warning set against the backdrop of the Asian financial crisis (AFC) should perhaps be reconsidered as part of a ringgit stabilisation strategy.

Thirdly, increase fiscal deficit to invest in DDI, including in research & development (R&D) and generate a job creation strategy at the heart of Malaysia’s macro-economic strategy.

It is recommended that a macro-economic strategy with jobs creation – including as part of the spill-over effects of R&D in green and renewable technologies – at its heart be part of the government’s priority for the next five to 10 years, even as the low-touch economy, digitalisation and automation increasingly become the new normal with COVID-19 as the impetus.

Fiscal consolidation in the medium-term, important though that it is, will have to be modified and adjusted according to business cycles and therefore shouldn’t be considered as cast in stone.

Fourthly, further diversify and boost trade and investment links beyond traditional FDI partners – looking to Latin America (Central & South), the Middle East, Central Asia, North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Beyond the immediate region, East Asia, North America and the European Union (EU), the Ministry of International Trade & Industry (MITI) through its two wings of the Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE) and the Malaysian Investment Development Authority (MIDA) should deepen Malaysia’s trade and investment linkages, respectively, with the rapidly-growing economies and emerging markets of Latin America, Central Asia, the Middle East & North Africa (MENA) and Sub-Saharan Africa. Argentina, for example, is steadily becoming an important trading partner.

From January to August 2020, both exports to and imports from Argentina grew by 23.4 and 20.1 percent, respectively, which outpaced Malaysia’s global trade record during the initial waves of COVID-19, according to Deputy-Secretary General of MITI, Hairil Yahri Yaacob.

Conclusion

Detractors do play a vital and indispensable role in keeping the government of the day on its toes. That said, Malaysia need not lament in despair and hopelessness at its current situation relative to the country’s neighbours in terms of FDI which stereotypically is seen as the “saviour” of the economy and economic development.

If there’s to be a new national consensus on the next phase in national development, let it be one that’s renewed by self-belief/confidence – avoiding the twin extremes of isolationism/autarky and over-dependence. Malaysia has what it takes to make that leap and transformation as a nation.

Related Articles: