Just a few days ago, ASEAN member state Malaysia made headlines when the country’s coastguard made its largest ever seizure of methamphetamine. It seized 2.12 tonnes of the drug disguised as tea in a shipment alleged to have come from Myanmar.

Zubil Mat Som, Malaysia’s Coastguard chief told the media that the drugs found on a boat in the northern state of Penang were worth around RM105.9 million (US$26.2 million).

"It is the coastguard's record-breaking seizure in its 15-year history," he said.

Prior to that, back in November, Hong Kong authorities also announced a record seizure of over half a ton of meth, saying that the coronavirus pandemic had led smugglers to riskier bulk shipments in place of traditional bulk mules. The drug was said to be worth around HK$300 million (US$39 million) and was discovered in a shipping container with a declared cargo of cement bags. The shipment was headed from Vietnam to Australia.

In some parts of the world, there has been an increased use of crystal meth in recent months. For example, the United States (US) Drug Enforcement Administration recently said that they have seen a surge in methamphetamine use during the health crisis.

In other regions like Asia – particularly Southeast Asia where the Golden Triangle is located – the drug trade is thriving even amid the pandemic.

To note, the Golden Triangle is the area where the borders of Thailand, Lao PDR and Myanmar meet at the confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers.

The Golden Triangle, coined by the US’ Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), is where most of the world’s heroin came from until the 21st century when Afghanistan became the world’s largest producer.

Drug producers in the region have since shifted their attention to meth and other synthetic drugs in recent years with most of the trade centred around Myanmar’s Shan state.

In the case of the aforementioned seizure in Malaysia, Zubil Mat Som said that "it is highly possible that the crystal methamphetamine was smuggled out from Myanmar's Golden Triangle."

Despite COVID-19

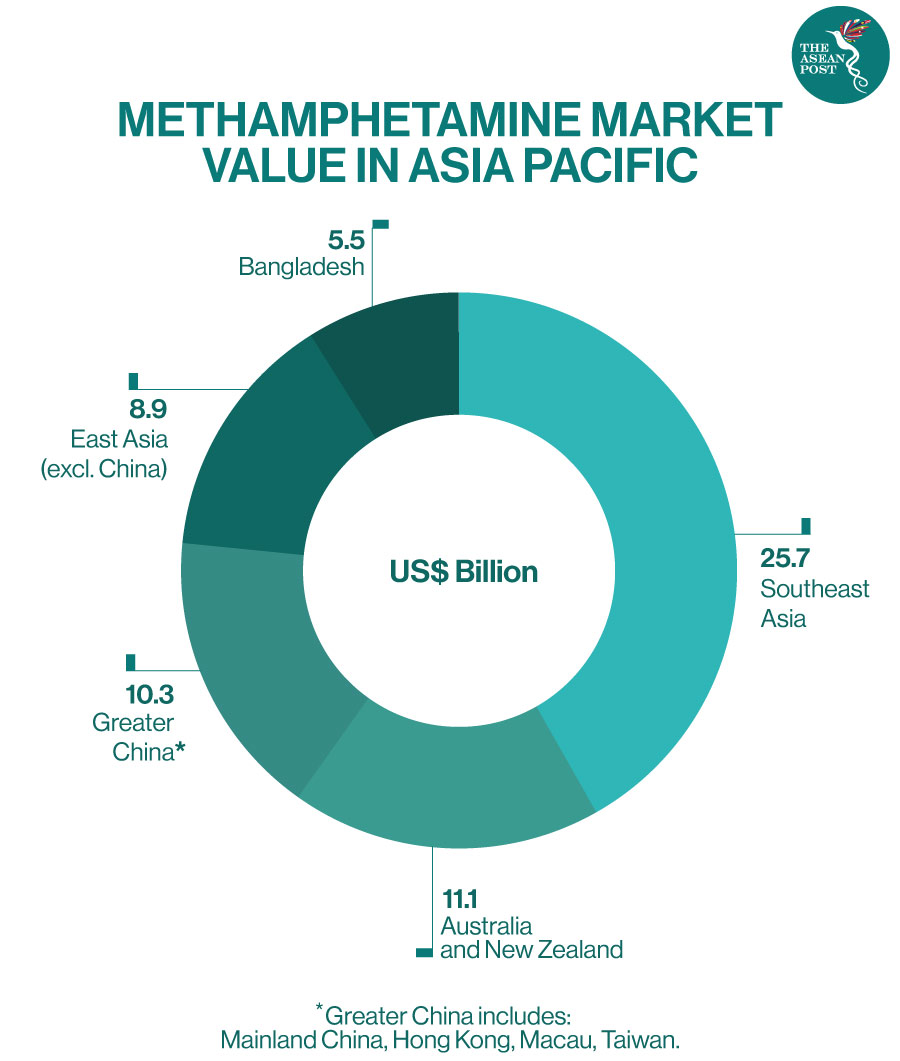

In 2019, it was reported that seizures of methamphetamine in East and Southeast Asia reached 140 tonnes. Whereas drug production and trafficking in the region last year generated profits of at least US$71 billion with methamphetamine accounting for US$61 billion – four times what it was six years ago.

But this year, despite COVID-19, its restrictions and increased number of border checkpoints – criminal networks have very quickly adapted, stated Gita Sabharwal, the United Nations (UN) Resident Coordinator in Thailand and Jeremy Douglas, the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

The pandemic has proven just how resilient transnational cartels dominating the meth trade truly are.

In their article titled, “Drug trade in Golden Triangle grows despite pandemic,” Sabharwal and Douglas explained that Thai drug traffickers have changed their routes to circumvent Chiang Rai and instead go through other provinces or via Lao and back into Thailand.

"We think it's business as usual in 2020, which is to say that supply is still surging just as it has been in the last few years," said Douglas. “If Myanmar, Thai, Vietnamese, Cambodia data is any indication – and we think it is – then at least within the Mekong the supply is as high or higher than last year in those countries,” he added.

Other than that, drug trade pattern on the consumer level has also shifted online as preventive measures limit people’s movement, said Paisith Sungkahapong, Thailand’s Deputy Secretary-General of the Narcotics Control Board.

“We have found an increase in the online drug trade via Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and also we found a lot of drugs being concealed and transported to buyers via the postal, public and private services,” he said.

In Thailand, authorities have employed new technologies such as X-ray devices – from hand-held to lorry-sized machines – to be used against illicit trafficking, including drugs and precursor chemicals that are vital to countering the destructive trade. Coordination efforts between police, customs, army, navy and border patrol officials across the region have also gathered and exchanged intelligence to take on organised criminal groups.

Nevertheless, in Sabharwal and Douglas’ article, they suggest that “to sustainably change, the reliance of communities on drug production and the corrosive impacts of illicit trafficking require going beyond a law enforcement response and engaging the social and economic dynamics.”

Related Articles: