China’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) celebrates its fifth anniversary this month. The euphoria that initially followed Chinese President Xi Jinping’s announcement in Kazakhstan and Indonesia has somewhat faded.

In its place is a West-driven narrative of a debt-trap: an “insidious plot” by China for world domination where China strikes opaque deals and inflates the value of projects, leaving poorer countries unable to repay their debts. China subsequently gains control of their land and resources. The United States (US) Secretary of the Navy Richard V. Spenser even described Chinese lending as “weaponising capital.”

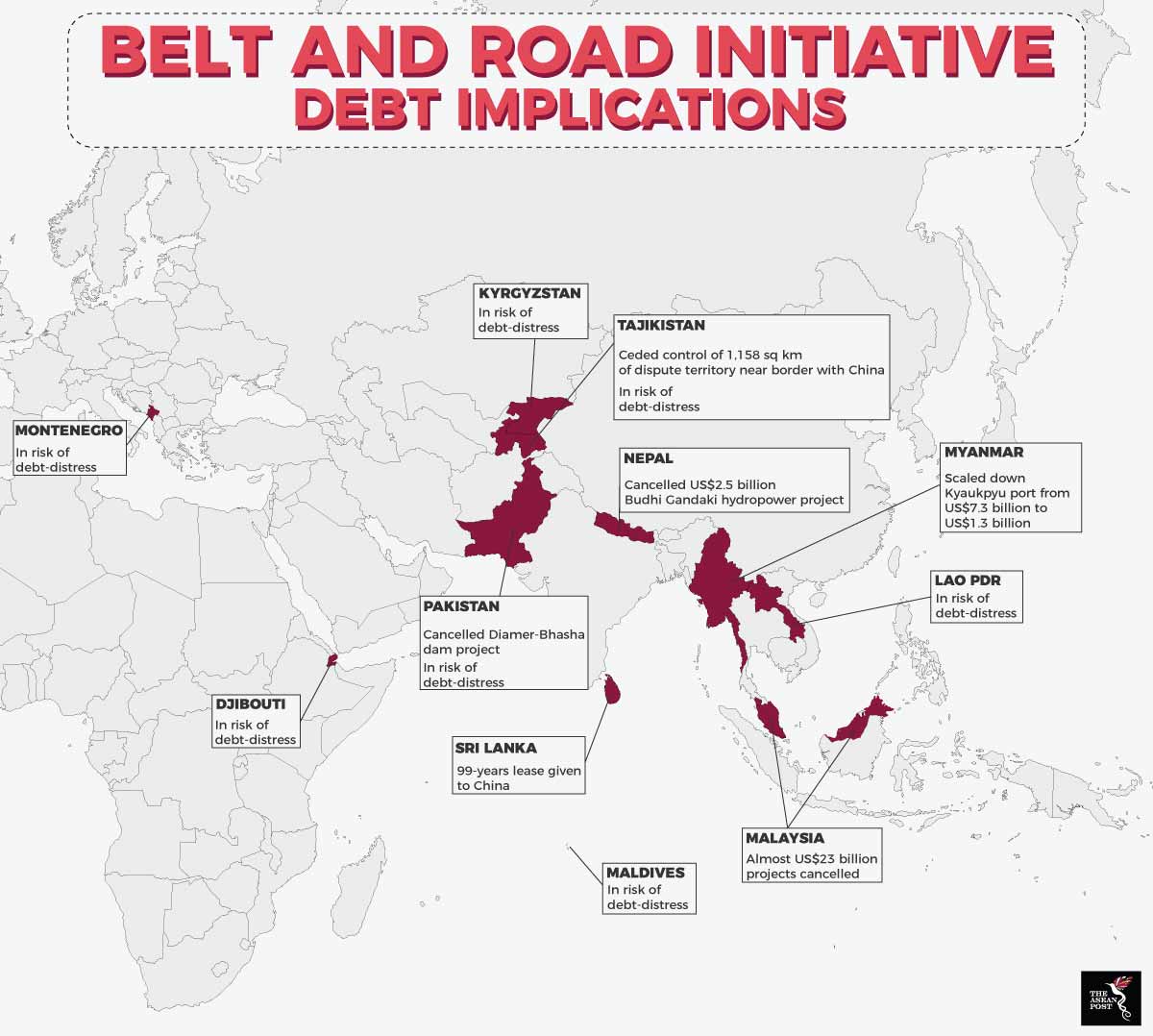

Sri Lanka is often trotted out as the poster boy for the debt-trap. The nation got into financial trouble constructing a port in Hambantota. Unable to fulfil its debt obligations to the Chinese, it was forced to cede control of the port and surrounding territories on a 99-year lease.

Tajikistan ceded control over some 1,158 square kilometres of disputed territory near its border with Xinjiang province to China in return for writing off an undisclosed loan.

The debt-trap narrative is backed by stories of pushback by the borrowing countries. Malaysia is frequently cited for cancelling projects worth almost US$23 billion, signed by the country’s previous government. The floodgates now seemed to have been thrown open as other countries have started cancelling or reviewing their own BRI projects.

Myanmar decided to scale down a new port in Kyauk Pyu from US$7.3 billion to US$1.3 billion. Kyauk Pyu is strategic to China as an alternative route for delivering oil and natural gas to the Yunnan province, bypassing the Strait of Malacca. Myanmar also declared that the project will be wholly financed by the private sector and further expansion will follow demand for it.

Pakistan recently cancelled the Diamer-Bhasha dam, a major China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project under the BRI. Similarly, Nepal called off plans for the US$2.5 billion Budhi Gandaki hydropower plant.

All vision, no master plan

In reality, the BRI is mostly a grand vision, not a master plan. To date, there is neither a blueprint nor any ministry assigned to plan or monitor the initiative. An Action Plan 2015-17 issued by the government’s Leading Group for Advancing the Development of One Belt One Road is barely seven pages long and contains ambiguous instructions such as “share responsibilities and progress together” and “plan collectively but go where the demand is.”

In China, the central government often issues broad directives and leaves the execution to lower-ranking officials. Various institutions get to work with little to no coordination between themselves. There is also no definition of what constitutes a BRI project or who can be a participant. This resulted in every investment project being labelled a BRI project, regardless of its origin, nature or viability.

Amidst the BRI frenzy, state companies took on projects quickly and gave out loans without considering their viability. The China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission recently estimated that Chinese banks had lent US$200 billion for 2,600 projects. Even then, not all Chinese overseas investments are state-funded. Private investors and ethnic Chinese from outside China are also involved.

Chinese companies usually do business with Chinese companies. In Sihanoukville, Cambodia, construction is mostly done by Chinese workers; Chinese tourists arrive in groups managed by Chinese tourist agencies, stay at Chinese-owned hotels, shop at Chinese-owned malls and eat at Chinese restaurants. All these activities are collectively blamed on China and the BRI.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

The BRI is largely fuelled by China’s large trade surpluses and foreign-exchange reserves. The country needed someplace to invest its money and to export its industrial surpluses.

BRI critics – mostly from the West – demonise BRI-related project failures as deliberate attempts to ensnare countries with debt they cannot repay. “It is even better for China that the projects don’t do well,” said Brahma Chellaney, who first coined the term “debt-trap diplomacy.”

If that were true, China will have to write off enormous sums as bad debt and imperil its own slowing economy. Furthermore, impoverishing its partner countries in exchange for land or resources will only go so far as China still needs markets to sell its products to.

If anything, China is more likely an inexperienced creditor, lacking the savvy of the Paris Club. The Paris Club is a forum of creditor nations that negotiates with financially distressed debtor countries on how to repay their loans.

Far from being predatory, China is also one of the biggest investors in the African continent. Beijing pledged US$60 billion in 2015 and another US$60 billion last month for further development.

Perhaps more cognisant of the unintended consequences of Western “debt-trap diplomacy” accusations, Xi stressed at the 2018 Summit of the Forum on China Africa Cooperation that the funding comes with no political strings attached. More importantly, steps will be taken to reduce risks and to ensure the projects are commercially viable and sustainable.

Related articles: