The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) prides itself on its ability to stave off geopolitical advances by greater powers by vehemently holding on to the principle of centrality. The notion, as was once illustrated by noted Singaporean diplomat, Bilahari Kausikan, is a “fluid” concept.

Kausikan makes it clear that centrality is a means for ASEAN states to better serve national interests as well as for great powers to achieve their goals and ambitions. As ASEAN members aim to reach that delicate balance of national interests and the interests of greater powers, essentially, they must be able to play on both sides of the fence.

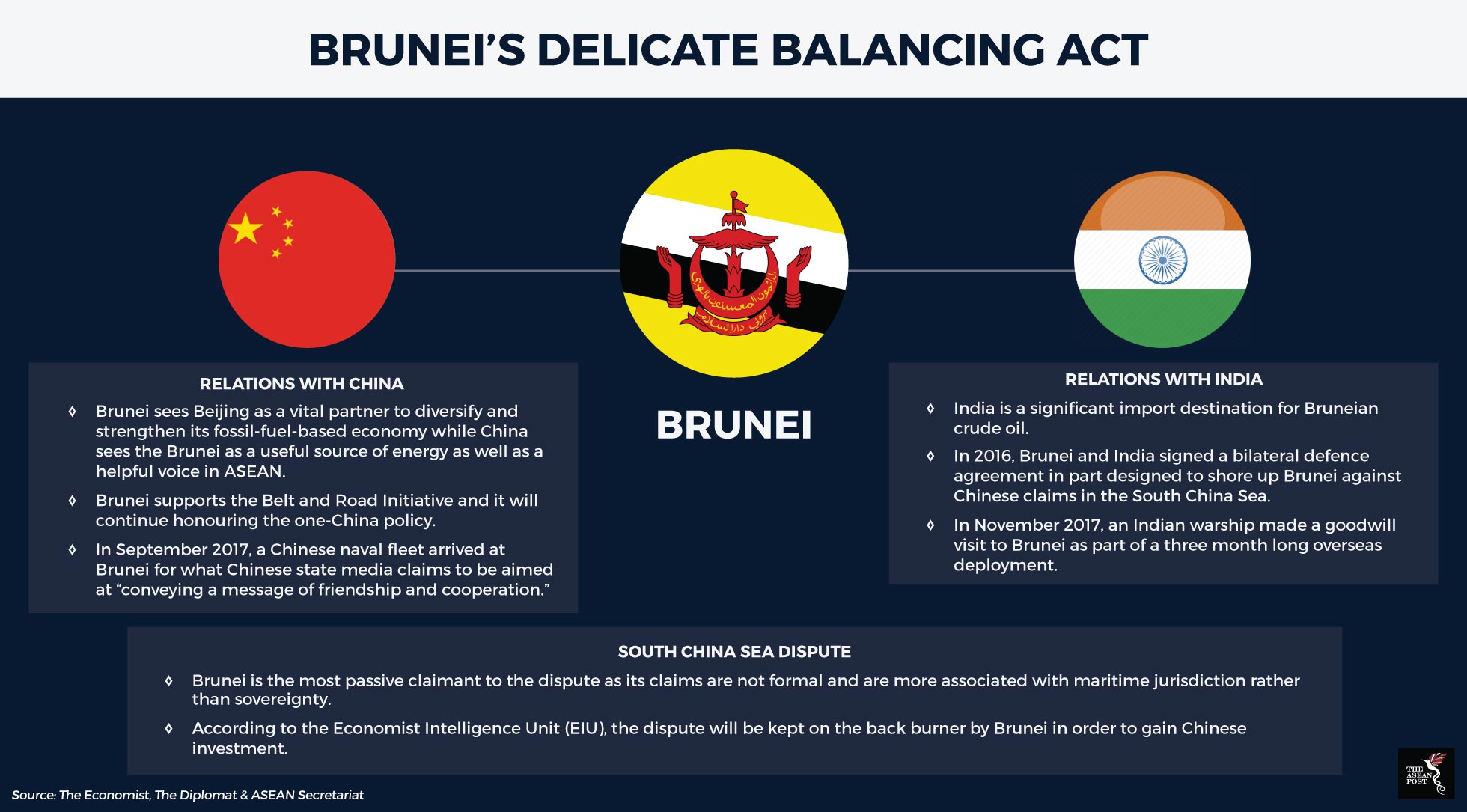

Such is the case with Brunei, which has successfully exemplified this tricky manoeuvre.

Between great powers

Brunei is an advanced nation but its economy is still very much dependent on fossil-fuels. In order to overcome this, the sultanate has been looking for ways to diversify its economy and promote investments into the country.

Always looking for the economic opportune moment, is China – which has snapped at the chance to invest in Brunei. September 2017 was a busy month in terms of bilateral relations between the two.

Within the span of 30 days, Brunei signed five key agreements with Chinese companies which would bring inward investments into the sultanate to the tune of billions of dollars and create jobs for local Bruneians.

Besides that, Brunei’s Sultan, Hassanal Bolkiah in a meeting with Chinese President, Xi Jinping in the same month, endorsed Beijing’s grandiose Belt and Road Initiative. He also reiterated his support for the one China policy.

Brunei, a claimant in the South China Sea dispute, continues to maintain strong military ties with China and even welcomed a Chinese naval fleet to its port in September 2017. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit, Brunei will continue being a “passive claimant” unlike other Southeast Asian claimants in order to shore up Chinese investments.

On the other hand, Brunei has also cosied up to India – an ally of the United States and staunch rival of China.

India’s economic growth has seen its oil imports increase and is Brunei’s third largest importer of crude oil at over US$1 billion annually. Besides that, under the Make In India initiative, India has invited investments from Brunei in various sectors including energy, information technology (IT), aerospace and manufacturing.

Furthermore, Brunei is home to an Indian diaspora of more than 10,000 strong, upon which Brunei-India ties can be developed further from a people-to-people context.

On top of that, Brunei has a bilateral defence agreement with India which can be viewed in part as a move to hedge against Chinese threats in the South China Sea. This defence collaboration was highlighted during then Indian Vice President, Hamid Ansari’s state visit to Brunei in February 2016.

“For some years now, Indian naval ships have been visiting Brunei and your ships have also participated in some of joint exercises. This has laid the grounds for deepening our cooperation in the defence sector, including by training of defence personnel in various fields,” Ansari said in an address at the University of Brunei Darussalam.

Toeing the balance

Brunei’s delicate balancing act epitomises how states can ensure national interests are met, while also relying on bilateral ties with opposing greater powers. The cherry to top off this diplomatic sundae is that neither power can ascertain as to whether Brunei is on their side or not.

This is important given the complexities of geopolitics today. ASEAN member states cannot pick either side. Neither can they pick no side – as their economic fortunes are very much intertwined with these great powers.

But threats to this balance still remain. At any given time, if Brunei pays more attention to one set of bilateral relations over the other, it could risk being cast as a client state of a particular power.

However, given the dexterity of the sultanate as it shifts and adapts to the contours of international relations, it seems like Brunei has it all under control.

Recommended stories: