Young people represent the fundamental drivers of economic and social growth and nowhere is this more visible than in Southeast Asia. In a region of more than 630 million people, 60 percent are below the age of 30.

However, in an ever-changing global environment, it is vital for the next generation to be prepared for challenges that may or may not be so apparent now. According to The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity, young people in developing countries – like most of Southeast Asia - will face the greatest challenges in the years ahead especially in employment.

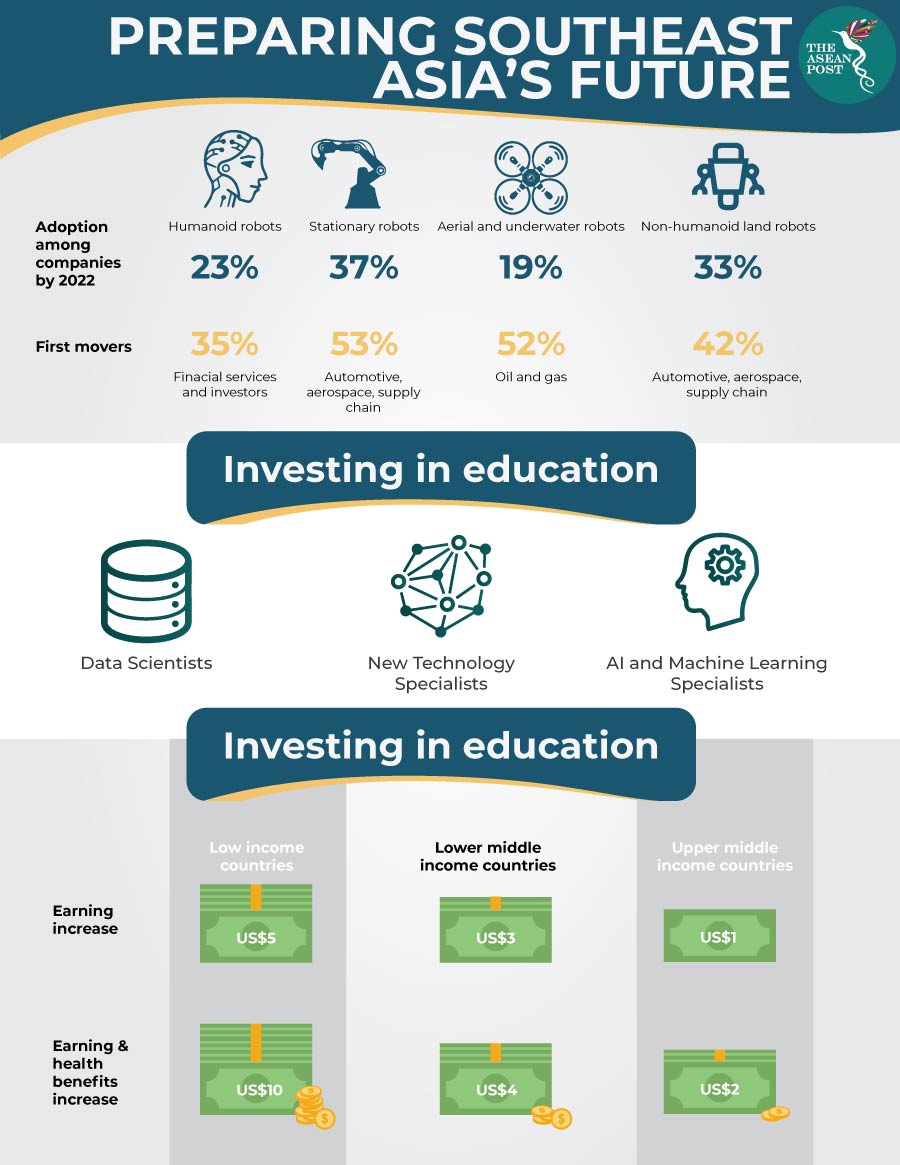

Approximately half – or two billion – of the world’s jobs are expected to disappear thanks to automation by 2030. In some countries, up to 80 percent of today’s jobs could be lost to industry-wide disruption.

Developing economies tend to be more susceptible to technology-induced unemployment due to the prevalence of many low-skilled and automatable jobs. Where in the past, many developing nations progressed by moving farm workers to factories, the next leap will see the creation of new growth models.

This will require higher skills levels than developing economies have to offer currently.

Educating the young

One way of bridging skills gap is to ensure adequate education for the younger generation. However, the numbers portray a worrying scenario.

By 2030, only half of young people in middle-income countries and 10 percent of young people in low-income countries will be on track to achieving basic secondary education. Within the East Asia and Pacific regions, more than 27 million adolescent boys and girls are out of the education system.

Despite efforts to improve access to education over the past decades, many across the region still fail to move on to tertiary education. Data by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) demonstrates that 7.2 million children are out of school at a primary level, 8.5 million are out at the lower secondary level and 18.5 million are out at the upper secondary level.

If young people aren’t sufficiently educated, they won’t be able to meet the rising demand for a skilled workforce in the future. This would result in major shortages of skilled workers in developing and developed economies and a glut of less skilled workers especially in low income economies.

Without proper action and investment in education, it is expected that more than a quarter of the population in low-income countries could still be living in extreme poverty in 2050. The case for education investment is indisputable as education is a basic human right and is critical for the long-term growth of a country.

The value of education will only continue to increase. As a population becomes more educated, its economic, social and demographic trends will improve further. For example, approximately one-third of reductions in adult mortality since 1970 can be attributed to gains made from better education for girls and young women.

Building skills of the future

For more developed economies, the uptake of 21st century skills and improving the employability of the young workforce is of paramount importance.

Forecasts by the United Nations (UN) indicate that the working-age population across ASEAN is expanding by an astounding 11,000 workers daily and this growth momentum would likely be sustained for the next 15 years. The breakneck pace of this demographic expansion is happening at a time when the Fourth Industrial Revolution is in full swing.

By 2020, this revolution would have brought us advanced robotics and autonomous transport, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning, besides modern materials, biotechnology, and genomics. Against this backdrop, employability in a modern world becomes more difficult as new skills need to be adopted.

Transforming the way young people learn will require innovation, entrepreneurial zeal as well as investments via public-private partnerships. The model of the traditional school and learning environment may have to be done away with and a more non-linear and consultative approach must be adopted.

This educational reform should facilitate the development of digital knowledge and technical skills as well as soft skills. To that end, the four C’s of 21st century learning – critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication – must be emphasised. It is in these areas, humans retain considerable advantage over our possible AI counterparts, hence it is a crucial skill to learn in order to futureproof the workforce.

Related articles:

Futureproofing ASEAN’s labour market