Recently, The ASEAN Post published an article on cyberbullying in Cambodia which pointed to results from the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) five-week poll involving one million young people as well as suggestions from its series of student-led #ENDviolence Youth Talks. Following its findings, UNICEF called on Cambodia to put in place a new policy that would help protect the nation’s children from cyberbullying.

It seems, however, that Cambodia isn’t the only country in the region that is facing an issue with policies to combat cyberbullying.

Towards the end of 2018, Indonesian actress Ussy Sulistiawati filed reports against several Instagram users for having posted insults aimed at her children’s physical appearances. What was worth noting about the case was that Ussy had filed reports against the perpetrators under the 2008 Electronic Information and Transactions Law which covers violations including electronic information or documents that contain insults or defamation.

Later, on 29 January, an article published on an online media outlet cited the case and pointed out that the problem with the current law was that it did not include specific provisions for the term “cyberbullying”.

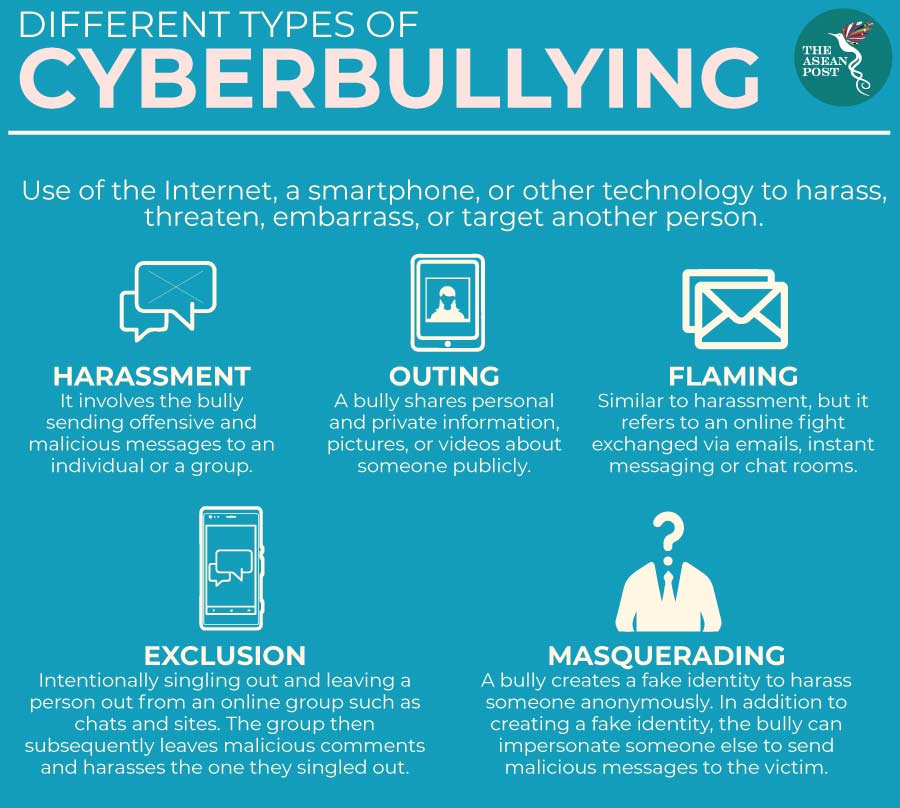

“This makes law enforcers assume that online insults and cyberbullying are the same thing when, in fact, they are different. Cyberbullying does not always take the form of insults. It can also often come in the form of threats and intimidation. Therefore, the law is ineffective at combatting cyberbullying in Indonesia,” the article read.

This matter is pertinent due to several factors which include the high internet penetration in Indonesia, the looming Fourth Industrial Revolution, and most importantly; the statistics related to bullying in Indonesia.

Cyberbullying concerns

In 2015, Indonesia’s Social Minister Khofifah Indar Parawansa said that 40 percent of children in Indonesia who commit suicide do so as a result of bullying. She added that she even knew of instances where student had cut their own wrists after being taunted to do so through text messages from bullies.

Three years earlier, in a 2012 survey released by Indonesia’s National Child Protection Commission (KPAI), 87.6 percent of 1,026 participants polled reported they had been bullied either physically or verbally in school. Many schools, the organisation found, are indifferent to bullying, considering it a natural part of their culture.

The more recent 2018 statistics from the KPAI are also gloomy. It reveals that out of the 161 cases of child abuse it received up until 30 May 2018, 22.4 percent of them involved bullying. Bullying was also the fourth highest cause of crime against children in the country in 2018 after law violations, abusive parents, and cybercrime.

Statistics from an anti-bullying movement in Indonesia, called Sudah Dong (translated to English as “Enough”) states that 10 percent of Indonesian students leave school because of bullying, 71 percent of Indonesian students regard bullying as a problem in their schools, while 90 percent of students from Standard 4 all the way to Year 2 in Middle School have reported being bullied in school.

Cyberbullying, on the other hand, is just a more technologically advanced version of what numerous children in schools all over Indonesia are already facing. And since Indonesia is advancing technologically, cyberbullying should be a worry.

According to We Are Social’s 2018 report, Indonesia has a 50 percent (132.7 million) penetration rate of Internet users, 49 percent (130.0 million) penetration rate of active social media users, 67 percent (177.9 million) penetration rate of unique mobile users, and 45 percent (120 million) penetration rate of active mobile social users. Visiting a social network (which is naturally where most cyberbullying occurs) was placed as the highest weekly online activity with 37 percent of said activity occurring via mobile phones, and six percent by computer.

The most connected demographic in Indonesia according to Indonesia’s Internet Service Provider Association are children aged between 10 to 14 years where penetration has already reached 100 percent.

ASEAN continues down the path of technological achievement and advancement. The bloc does not want to be left behind and certainly wants to remain relevant in an increasingly technologically advanced world. These aspirations are no different for Indonesia but while technology does present many advantages and opportunities, it is not without its dark areas. In order to truly usher in the future, ASEAN must also look at (and address) the challenges that come with it. Cyberbullying is one of those immediate challenges.

Related articles: