The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) has released the results of a five-week poll involving one million young people and suggestions from a series of student-led #ENDviolence Youth Talks. The talks were held in more than 160 countries, including Cambodia.

Among the findings from the poll and youth talks was that 85.7 percent of young Cambodians aged between 15 and 25 years are in danger of online violence, cyberbullying and digital harassment.

Following the discovery, UNICEF called on Cambodia to put in place a new policy that would help protect the nation’s children from such bullying. In a statement released to coincide with Safer Internet Day last Tuesday, Natascha Paddison, UNICEF’s representative in Cambodia, said the Internet had become ruthless and void of any form of kindness, and young people were continuously exposed to online harassment.

“We’ve heard from children and young people from around the globe and what they are saying is clear: The Internet has become a kindness desert,” she said.

Breeding ground

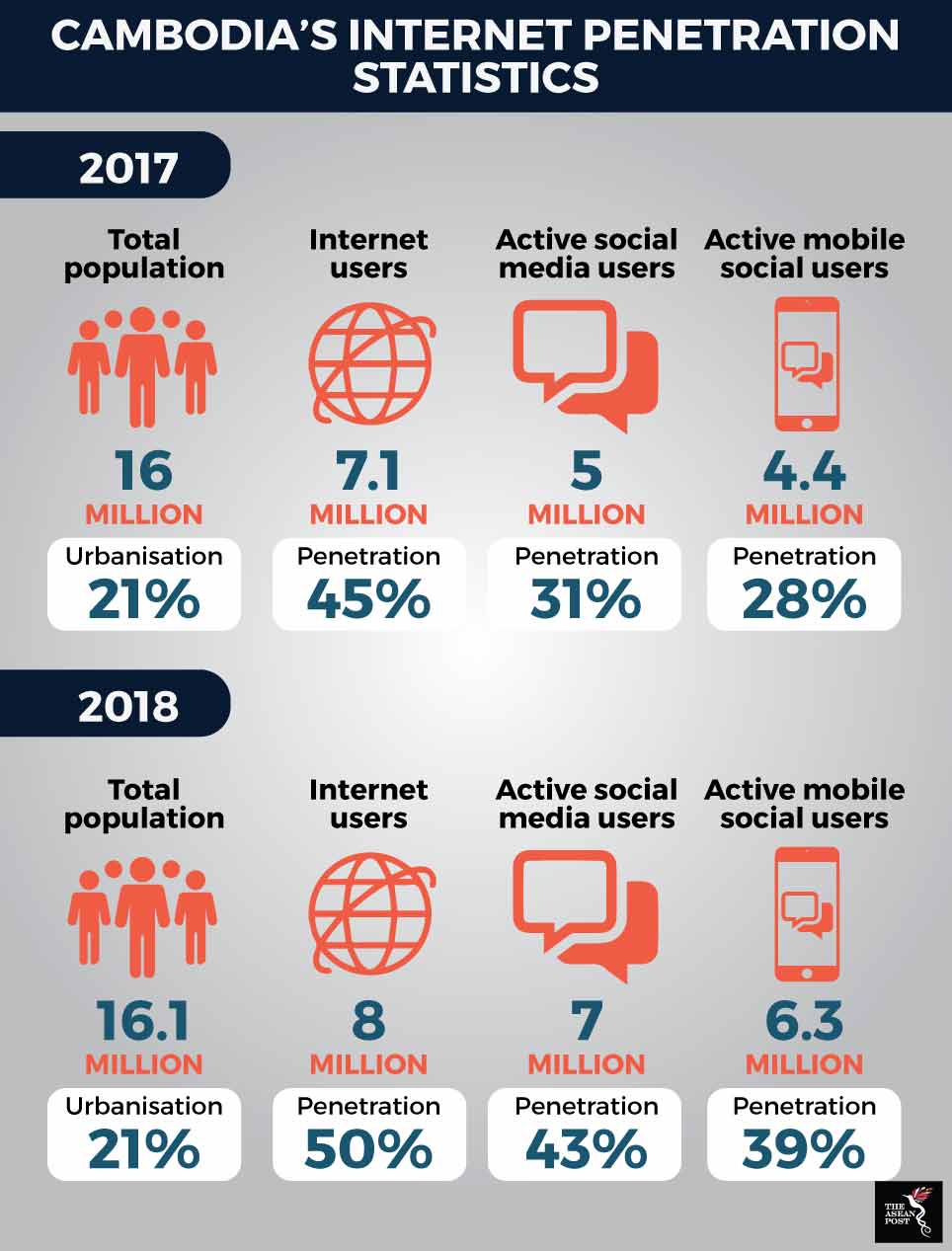

Internet penetration in Cambodia has been growing rapidly. According to statistics from We Are Social, Cambodia managed to grow its internet penetration from 45 percent of its population in 2017 (15.9 million) to 50 percent of its population in 2018 (16.1 million). In total, that’s an increase of 843,000 internet users which means Cambodia managed to grow its internet users by 12 percent.

While the 2019 results are not out yet, there is little reason to doubt that internet penetration will continue to grow even more by the end of 2019.

Source: We Are Social

Source: We Are Social

While it is certainly good news that Cambodia is developing at such a rapid rate, the speed of development does not come without a price. The obvious fact is that better internet penetration also leads to a more fertile breeding ground for cyberbullying as well.

Cyberbullying versus traditional bullying

Back in 2012, in Ireland, a paper entitled, “Living in an ‘electronic age’: Cyberbullying among Irish adolescents” by Pádraig Cotter and Sinéad McGilloway from the National University of Ireland, Maynooth took a closer look at cyber bullying in Irish schools.

They interviewed 122 pupils, aged 12 to 18 years, in two co-educational schools in the south and explored four main forms of cyber bullying - text message, email, phone call and picture or video clip.

The teens surveyed said cyberbullying was the worst kind of bullying because they “can’t escape it”, even when at home and because pictures and messages can be spread easily and quickly. Pictures, video clips and phone calls were the worst type of cyberbullying according to the pupils interviewed, and less likely to be noticed by an adult in comparison with traditional bullying. More than a quarter of cyberbullying victims did not know who their cyberbullies were.

Anonymity, the quick spread of information and the fact that – unlike traditional bullying – cyberbullying had no “closing time”, all provided an argument for cyberbullying being worse than traditional bullying.

However, a later study in 2013 entitled, “Is cyberbullying worse than traditional bullying? Examining the differential roles of medium, publicity, and anonymity for the perceived severity of bullying” by researchers Fabio Sticca and Sonja Perren from the University of Zurich revealed that it wasn’t the medium that dictated the severity of the bullying. Results of the study simply showed that public scenarios were perceived as worse than private ones, and that anonymous scenarios were perceived as worse than known ones.

Emulating Singapore

While Malaysia is currently still planning to enact a law that will make cyberbullying illegal, Singapore is currently the only country in ASEAN which has officially made cyberbullying a crime.

Under the Protection from Harassment Act 2014 (PHA), harassment, stalking, and other anti-social behaviour have been criminalised. The law is designed specifically to make acts of cyberbullying and online harassment a criminal offence.

This, unfortunately, does not mean that Singapore has become free of cyberbullying. In fact, a survey commissioned by Singapore’s Mediacorp programme Talking Point in March last year found that three-quarters of children and teenagers polled in Singapore said they had been bullied online, and almost all the victims did not inform their parents.

Talking Point’s survey involved 353 youths mostly between the ages of 13 and 19.

The question is whether Cambodia should take a cue from Singapore and, as UNICEF suggests, put in place a policy to protect the nation’s children from cyberbullying?

There is a possibility that enacting such a policy would at least decrease – if not eradicate – cyberbullying in the country. But on the other hand, such laws can easily be abused to stifle freedom of speech which already has many Cambodian activists concerned about. It is more than likely that a holistic approach will be needed to address Cambodia’s worrying cyberbullying statistics.

Related articles:

Cybercrime laws and conflicts of interest