On 26 January, Cambodian student Kong Bunrith posted a video on Facebook accusing senior officials in the country’s Ministry of Justice of allegedly taking bribes. Kong had claimed that some of his peers paid up to US$150,000 in bribes to secure passing grades.

The municipal court has since summoned him for questioning over accusations of public defamation, slander and incitement to discriminate. The date is set for this Friday, 14 February.

In Kong’s seven-minute video clip on Facebook, he speaks of activities and procedures of corruption, claiming that about 50 students paid bribes totalling as much as US$3 million. He also mentions several Ministry of Justice senior officials involved in the alleged collection of bribes.

When interviewed, Kong told local media that the information he shared in his video came from sources who messaged him privately, adding that he was expected to share the information that was passed on in hopes that it would lead to a full investigation.

“All the things in the video are just clues showing irregularities in the student examination. I decided to read the message someone sent to me. As I read them, I didn’t know whether they were true or not,” he was quoted as saying.

The case brings to light a problem that has been plaguing Cambodia for a long time now: alleged corruption in the education system.

In January 2018, Christopher Hammond from the University of Oxford cited Walter Dawson from the College of Education, Hanyang University in Seoul, Korea, who wrote in 2010 that low salaries were a frequently cited reason teachers gave for “forcing” public school students to pay for private tuition (PT).

“However, these corrupt practices are situated in a broader hierarchy of corruption. Students and families paying their own teachers for supplementary lessons constitutes the lowest level of the hierarchy.

“Above this level, however, teachers themselves are often forced to pay ‘facilitation fees’ to their schools in order to receive their salaries. A similar practice occurs at the next level, where 64 percent of school directors must pay fees to district offices to receive funding to operate their schools. At the top of the pyramid are a range of administrative and political officials who siphon funds for education off before they even reach the districts.”

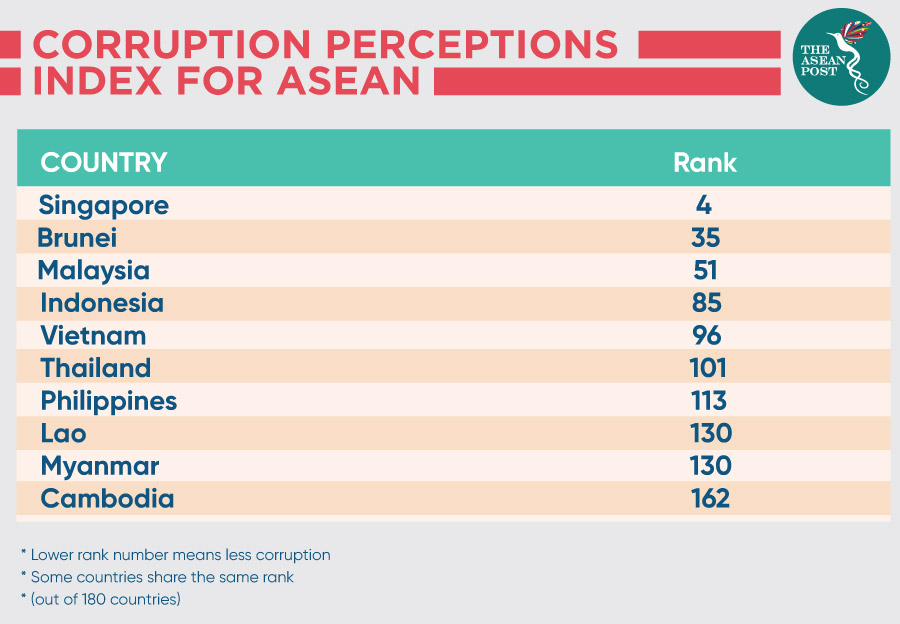

Transparency International’s (TI) recently released Corruption Perceptions Index 2019 gave Cambodia a score of 20 (a higher score means less corruption with 100 being completely clean), one point lower compared to previous years.

Government efforts

Nevertheless, Cambodia’s Higher Education Association (HEA) claims that it has nearly eradicated corruption in the education system, owing to “a series of reforms” carried out by the Education Ministry that started back in 2013.

During a Cross-Talk discussion with a Cambodian daily on 10 January, HEA chairman Heng Vanda said corruption in education had decreased by 90 percent.

The country’s National Assembly in November approved a budget of US$915 million for the education sector in 2019, an increase from 2018’s US$848 million. The budget allocation for next year will inject cash into teachers’ wages, school building and reforming seven major educational programmes. The minimum salary of each teacher will jump from about US$285 per month to US$292 in January, and again to US$300 by April.

Nevertheless, some observers remain unconvinced.

Ouk Chhayavy, president of the Cambodian Independent Teacher’s Association, was quoted as saying that corruption in the sector had decreased, but claimed that Vanda’s statement was misleading.

“I see that education in our country is doing better than before, but bribery is still going on – it’s just not as apparent as it used to be. Corruption is a disease that we cannot cure,” she said.

San Chey, executive director of the Affiliated Network for Social Accountability, was also quoted as saying that bribery remains a critical issue plaguing the education sector.

“Some teachers and staffers downtown still take money from students. This doesn’t happen in rural areas because students and teachers there are poor,” he said.

Therefore, the question is whether Kong’s call for the information shared with him regarding corruption to be fully investigated is fair. Considering Cambodia’s struggle with corruption in the education system, the answer to this is most likely a “yes”.

Related articles: