The ongoing pandemic might have slowed down the advancement of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), but not its coverage in the media.

Pundits and scholars across the world have kept publishing opinion articles and analyses on a daily basis speculating about its demise, or its reboot. The initiative has been accompanied by criticism and accusations since its inception and opinions are still mixed.

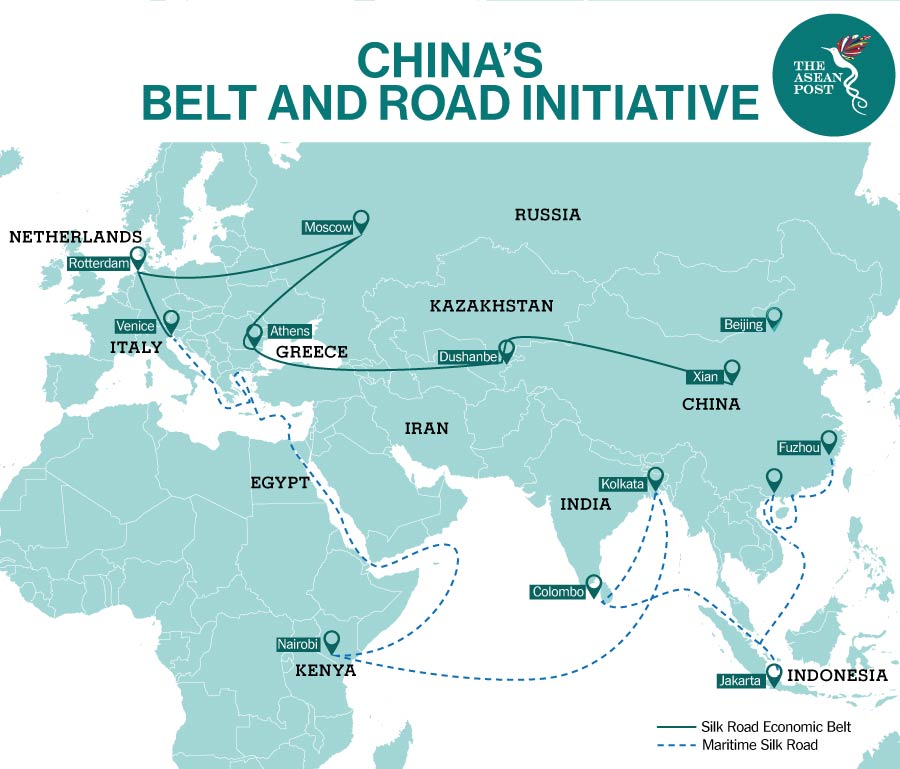

Although military concerns are present, Xi Jinping’s connectivity masterplan is predominantly covered and assessed from economic and geopolitical perspectives. Several major projects have been closely scrutinised because of “debt trap” concerns in which the hosting country would have to make concessions to China if debts are not paid. The most-often mentioned case is the Port of Hambantota in Sri Lanka that eventually resulted in China securing a 99-year lease of the port itself. However, these accusations seem to have been overblown as there is limited evidence to support China’s “debt-trap diplomacy” intentions.

Across Southeast Asia, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Reconnecting Asia’s database lists dozens of ongoing projects under the BRI, such as roads, powerplants, and railways. The latter are arguably the ones that receive the most attention and affect several ASEAN member states.

After multiple delays, Lao’s segment of the Kunming-Singapore Rail Link is now in an advanced stage while Thailand has recently signed an agreement with China to build a further section. At the same time, in Indonesia, the Jakarta-Bandung rail still appears to be “going nowhere” after five years, while in Malaysia – following an arguably successful renegotiation of the East Coast Rail Link – a major port project has just been cancelled.

When presenting the BRI to the world, the outlined priorities were policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, trade, financial integration, and people-to-people bonding. Although the hard, tangible part of the initiative could easily be seen when a bridge or a railway is completed, the surrounding softer side is often overlooked.

If a company from a foreign country has built a powerplant and left, the footprint is likely to be minor. But if another country, such as China, is embarking on a quest to reconnect the world to itself, the implications are deep and multifaceted.

If China builds a bridge or a road that allows people to reduce considerably the traveling time to visit their relatives, it could result in goodwill. If China builds a railway that brings new commercial opportunities and tourists, a similar sense of recognition and gratefulness might arise. If China contributes to the development of a new national 5G network and smart cities, perhaps while also fostering collaboration and exchanges between local and Chinese researchers; politicians and the media are likely to recognise the merits of Beijing.

Surely, the aforementioned examples might come with a darker side, such as environmental concerns, exploitation, and competition from Chinese companies and business people, or overall concerns of technological and economic overdependence.

That said, the implementation of these initiatives and whether the soft-power factor is valued or not is ultimately in the hands of the decision-makers. Negative publicity might result in a worsened reputation, and this should be prioritised when considering China’s “peaceful rise” (or development) rhetoric.

Beijing seems confident that it has the means and capabilities to succeed in the advancement of the BRI, but although the infrastructural needs of Southeast Asia and other developing countries are urgent, the sole influx of finances without considering the softer side is poised to be a major hindrance.

Observers in the region seem to have a sceptical view of the initiative, as shown in The State of Southeast Asia’s survey report, with limited variations between 2019 and 2020. China’s win-win rhetoric is struggling to convince regional actors, apart from those who might benefit directly from it, economically and politically.

Soft power, however, works best when it reaches wider audiences that could in turn unite their voices to leverage decisions, such as openly welcoming foreign companies and investments to develop a new macro project seen as beneficial to the community.

In addition to infrastructure projects, the BRI extends to other spheres such as the digital silk road –based on new information and communication technology – or the health silk road – now further spurred by the ongoing CIOVID-19 pandemic – that involves medical supplies and technical know-how such as the production and distribution of vaccines.

Due to the pressing relevance of the latter, China appears to have embarked on a so-called vaccine diplomacy. Considering that several wealthy countries have been accused of “hoarding” vaccines, the opportunity for Beijing to distribute vaccines among developing countries combined with assistance for post-emergency recovery might have a significant impact on China’s image and reputation.

In a nutshell, the BRI’s potential is undeniable but the negotiation, execution, and reception are still in the making. Beijing might want to double down on its efforts to elevate the embedded soft-power factor in its grand connectivity masterplan.

Although relations with the United States (US) are tense and clearly defined by hard power interactions, China’s relations with countries that have joined the BRI ought to be characterised by a combination of soft and economic strategies to pave the way to stronger and long-lasting collaboration.

Ultimately, the post-pandemic period could prove crucial to revamp this ambitious effort while also constituting a unique opportunity for Southeast Asia and its people.

Related Articles: