Parents in Thailand are split as to whether corporal punishment for their children is the right way to go.

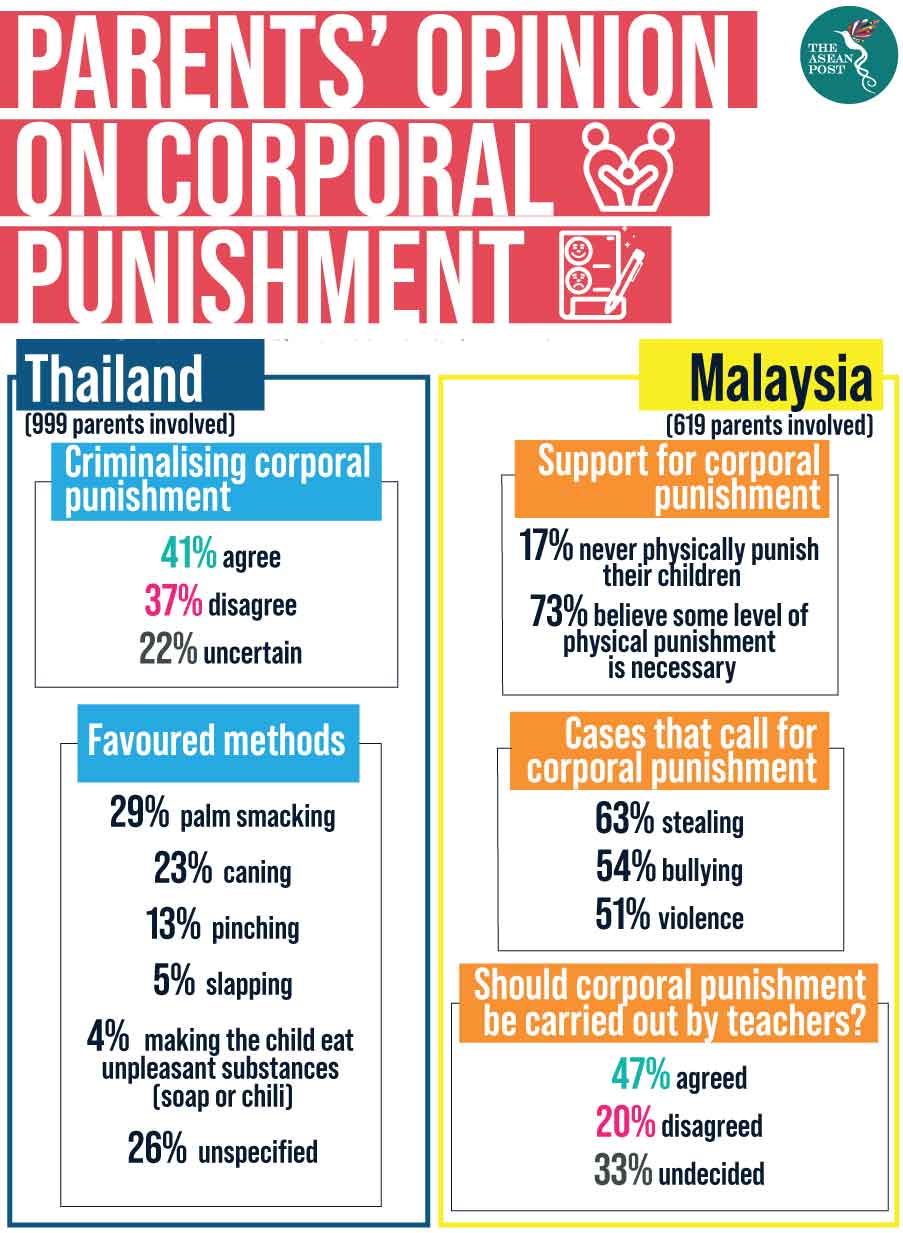

A recent survey of 999 Thai parents by YouGov found that two in five believe that physical punishment should be illegal, while another two in five believe that physical punishment is normal. The remaining one in five are undecided.

The survey was conducted by United Kingdom (UK)-based market research company YouGov, which (from 26 June to 3 July) randomly selected parents from a pool of 165,000 Thais who signed up to participate in return for compensation. YouGov states the study has a margin of error of three percent.

Seven out of 10 (71 percent) parents answered that physical punishment is “sometimes necessary.” The top three activities where parents felt physical punishment was acceptable were for stealing, violence, and bullying.

“While it appears most Thai parents are comfortable with physically disciplining their children at home, they are split over whether the law should come into play,” said Jake Gammon from YouGov.

Recently, news reports in Thailand revealed that a 23-year-old Samut Prakan mother who, along with her new 26-year-old husband, hit her five-year-old daughter to the point of hospitalisation. Both were arrested and charged with domestic assault.

The survey did not include questions on corporal punishment outside of the home, such as in schools. However, in a similar study in neighbouring Malaysia, YouGov found that 47 percent out of the 619 parents agreed that physical punishment should be carried out by teachers. Only 20 percent of those polled disagreed, while the rest were undecided over the matter.

Up to 81 percent of the 619 Malaysian parents believe that corporal punishment is necessary.

Spare the rod?

There have been many arguments either supporting or opposing the use of corporal punishment on children. Most of the more recent arguments, however, have been those arguing against the use of the cane.

In November, the American Academy of Paediatrics released a statement warning against the harmful effects of corporal punishment in the home. The group, which represents about 67,000 doctors, also recommended that paediatricians advise parents against the use of spanking, which it defined as “non-injurious, openhanded hitting with the intention of modifying child behaviour,” and said to avoid using nonphysical punishment that is humiliating, scary or threatening.

“One of the most important relationships we all have is the relationship between ourselves and our parents, and it makes sense to eliminate or limit fear and violence in that loving relationship,” said Robert D. Sege, a paediatrician at Tufts Medical Center and the Floating Hospital for Children in Boston.

The American Academy of Paediatrics also asserted that spanking may not decrease negative behaviours and might instead increase aggression. The study instead recommended non-physical disciplinary methods such as time-outs, ignoring bad behaviour, and positive reinforcement.

Even much earlier, in March 2003, The Society for Adolescent Medicine released a paper concluding that corporal punishment in schools is an ineffective, dangerous, and unacceptable method of discipline.

“The use of corporal punishment in the school reinforces physical aggression as an acceptable and effective means of eliminating unwanted behaviour in our society. We join many other national and international organisations recommending that it be banned and urge that nonviolent methods of classroom control be utilised in our school systems,” the society wrote.

On the other side of the stick, however, most of the support for corporal punishment seems to be rooted in traditional family values and religious beliefs. Professor of Human Development and Family Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin, United States (US), Elizabeth Gershoff, argues that corporal punishment in the US is largely supported by "a constellation of beliefs about family and child rearing, namely that children are property, that children do not have the right to negotiate their treatment by parents, and that behaviours within families are private".

Even then, those who have spoken up in defence of corporal punishment have often placed an ultimatum next to it.

According to a Time article in 2014 by psychologist Jared Pingleton, spanking can be an “appropriate form of child discipline,” but only for cases of “wilful disobedience or defiance of authority – never for mere childish irresponsibility.”

He also warned that parents with difficulty controlling their tempers should refrain from corporal punishment since “it should never be administered harshly, impulsively, or with the potential to cause physical harm.” He also recommended stopping the practise of spanking for adolescence.

Pope Francis has declared his approval of the use of corporal punishment by parents, as long as punishments do not "demean" children. The Vatican commission appointed to advise the Pope on sexual abuse within the church, however, criticised the Pope for his statement, contending that physical punishments and the infliction of pain were inappropriate methods for disciplining children.

In many parts of the world, corporal punishment has been made illegal. Some parents, however, argue that it is their absolute right to raise their children the way they see fit as long as their actions do not fall under abuse. “Abuse” however is also subjective. In the end, the matter of whether to spare the rod or not will be something that requires (and deserves) more focus and deliberation before a conclusion can be made.

Related articles: