Children around the world are not getting the nutrients they need, undermining their capacity to grow, develop and learn to their full potential. According to the State of the World’s Children 2019: children, food and nutrition’ report by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), one in three children under five is not properly growing due to malnutrition. The triple burden of malnutrition – undernutrition, hidden hunger and overweight – threaten the survival, growth and development of children, as well as economies and nations.

In Vietnam, childhood obesity was not a problem before 1995. The 2016 ‘Global health observatory data repository,’ study by the World Health Organization (WHO), showed that Vietnam has the lowest prevalence of overweight youth (2.6 percent) compared to other ASEAN countries.

Vietnam also boasts of having among the healthiest and most balanced meals in the world, where some dishes serve all the needed requirements of protein and vitamins.

Unfortunately, Vietnam’s strong economy and globalisation have changed the eating habits of its people. The rising affluence in Vietnam has encouraged the consumption of highly processed foods that are enriched with artificial flavourings, sugar and other chemicals. Combined with a sedentary lifestyle, it is only natural that Vietnamese children now face a growing prospect of obesity.

Childhood obesity

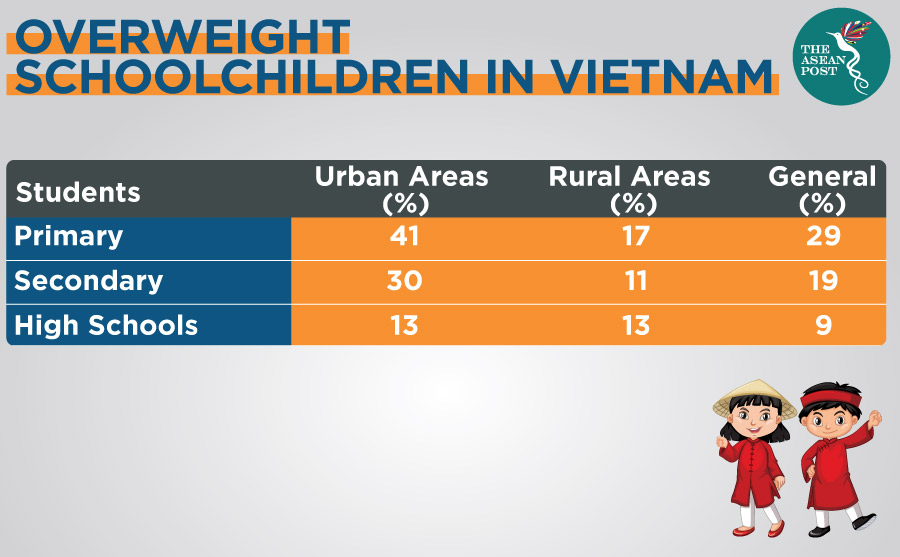

A 2017 study by the National Institute of Nutrition (NIN) found that 29 percent of primary school students are overweight and obese, while the rate of overweight students in secondary schools and high schools are 19 percent and 9.5 percent, respectively. The incidence of overweight and obesity is higher in urban children (42 percent) than in children in rural areas (35 percent).

Vietnamese are consuming more meat than vegetables. Over the past 30 years, meat consumption by an average Vietnamese has increased by six times to nearly 100 grams (g) a day. Children are also replacing grains, fruits and vegetables for more convenient high-sugar, high-calorie fast foods. NIN’s study found that overweight children consume more protein-rich food and sweet products.

“The taste preferences that children develop start from a very young age,” said Alissa Pries, advisor at the Helen Keller International’s Assessment and Research on Child Feeding (Arch) Project. She added that children who are exposed early to foods high in sugar or salt can influence their diet choices later into adulthood.

Another contributor to increased obesity rates among children is the high screen time. Parents are mixing screen time with mealtime to keep their children seated while eating. Experts say that this trend would have long-term health effects, including damage to the mental development of Vietnam’s youth.

Dr Pham Minh Triet, a former head of the psychology department at Children’s Hospital 1 in Ho Chi Minh City, said that studies have linked watching television during meals to obesity, which can lead to health issues such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease.

A 2017 Stanford University survey revealed that Vietnam is among the least physically active countries in the world. The report revealed that an average person in the state walks only 3,600 steps a day, compared to 4,000 steps in the Philippines and 4,763 in Thailand. Children are less active, with about 46 percent of students in secondary school and 39 percent in primary schools in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City not doing enough physical activity.

To make matters worse, according to Nielsen’s 2017 report on Gen Z’s consumer trends, youth aged between seven and 22 in Vietnam prefer to spend their leisure time either watching TV (90 percent) or going to a bubble tea shop (81 percent).

This increasing prevalence of obesity in Vietnam poses a threat to the country’s social and economic systems, including the rising cost of healthcare, productivity losses from absenteeism or sickness and productivity losses from early deaths.

Socio-economic status and parents’ education levels also factor into the rising obesity trends. The NIN study revealed that malnutrition is higher in rural areas. The study also found that 23.8 percent of children under the age of five are stunted or malnourished.

Children are malnourished

Despite considerable strides in national health in recent decades, as many as 1.9 million young children are malnourished because of improper care, said Truong Tuyet Mai, head of the NIN.

“While Vietnam has made good progress in reducing its rate of undernutrition in recent decades, chronic malnutrition or stunting remains unacceptably high, and there is a risk that rates of overweight will rise,” said Rana Flowers, UNICEF Representative in Vietnam.

Malnutrition is highest among secondary students (13 percent), followed closely by high school and primary children with 12 percent and 7.5 percent, respectively. Malnutrition and obesity increase the risks of chronic diseases like diabetes, high blood pressure and coronary artery disease.

Intervention programmes are needed to prevent malnutrition among rural children while appropriate diets and physical activities are essential to encourage healthy living among urban children. Nutrition education can also empower families and children to make healthier life choices.

By 2025, Vietnam aims to reduce childhood malnutrition and stunting rate to less than 20 percent and obesity rate among children, to less than 12 percent.

Related articles: