2020 was one of the hottest years ever recorded since time immemorial.

According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the average global land and ocean temperature last year was the highest ever measured, edging out the previous record set in 2016 by less than a tenth of a degree.

The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) too announced recently that 2020 “rivalled 2016 for the top spot,” adding that the years from 2011 to 2020 had been the warmest decade recorded. However, 2016, 2019 and 2020 are said to be the warmest years recorded – and the differences between them in average global temperatures were “indistinguishably small.”

“The confirmation by the WMO that 2020 was one of the warmest years on record is yet another stark reminder of the relentless pace of climate change, which is destroying lives and livelihoods across our planet,” Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN) said.

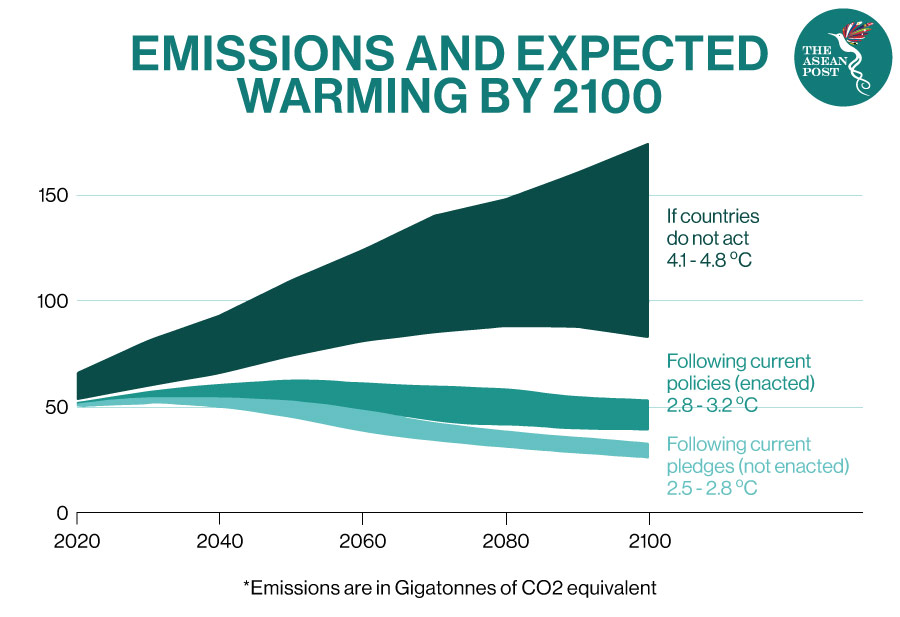

“We are headed for a catastrophic temperature rise of three-five degrees Celsius (C) this century. Making peace with nature is the defining task of the 21st century. It must be the top priority,” he added.

Scientists have warned that average temperatures will keep increasing due to the huge amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) expelled into the atmosphere. Although GHG declined by around seven percent globally in 2020 due to coronavirus lockdowns, it was not enough to affect temperatures.

The 2015 Paris Agreement calls for limiting global warming to well below two degrees C, preferably to 1.5 degrees C, compared to pre-industrial levels (1850-1900). However, the WMO suggests that there is at least a one in five chance of the average global temperature temporarily exceeding the 1.5 degrees C mark by 2024.

According to media reports, the average global temperature in 2020 was about 14.9 degrees C – 1.2 degrees C above the pre-industrial level.

Rising heat in the atmosphere and water is causing glaciers to melt, rising sea levels, and also fuelling larger and more destructive natural disasters such as storms and cyclones.

From the United States (US) to some parts of Southeast Asia, a number of catastrophes have hit these areas last year, causing numerous deaths and extensive damage.

“Global warming won’t necessarily increase overall tropical storm formation, but when we do get a storm, it’s more likely to become stronger,” said Jim Kossin, an atmospheric scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “And it’s the strong ones that really matter.”

Childhood Malnutrition

Other than the aforementioned implications of climate change, its impacts extend far beyond extensive damage to the environment.

A research published yesterday in the journal Environmental Research Letters suggests that climate change may contribute more to greater malnutrition and poor diet among children – than other causes such as poverty and poor sanitation.

While childhood malnutrition has declined globally over the last few decades, undernourishment has increased since 2015. This is in part due to warming temperatures and extreme weather.

Researchers from the University of Vermont in the US examined diet diversity among more than 100,000 under-fives in 19 low-income countries across the world. They found that higher temperatures were associated with significant reductions in the quality of diet in five of the six regions studied – Asia, Central and South America, North, West and Southeast Africa.

Iron, folic acid, zinc and both vitamins A and D are all crucial for the physical and mental development of children. Unfortunately, rising carbon pollution has been shown to reduce the levels of these essential micronutrients in many crop staples such as wheat and legumes.

Higher temperatures can directly impact the yield of staple crops and reduce livestock productivity which then increases food insecurity; impacting child nutrient intake.

Moreover, malnutrition also carries major economic costs. In 2019, the World Bank stated that the economic costs of undernutrition were around five to 11 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in Africa and Asia.

The authors of the US study called on governments to incorporate climate change into their plans for improving diets for the most vulnerable children.

"Continued environmental degradation has the potential to undermine the impressive global health gains of the last 50 years,” said Taylor Ricketts, director of the University of Vermont's Gund Institute for Environment.

Related Articles: