The coronavirus pandemic does not discriminate. The deadly COVID-19 virus infects anyone exposed it regardless of age, ethnicity, gender or living conditions. When it comes to the impacts of the crisis - livelihoods, local industries, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and even large corporations are severely affected. Everyone is feeling the pinch from the pandemic.

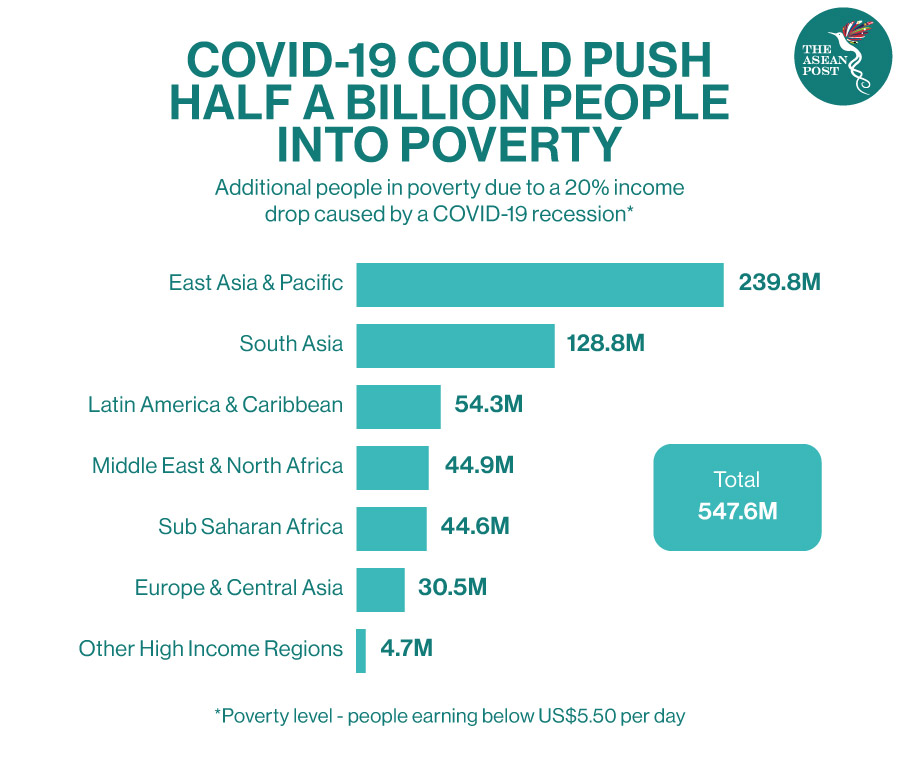

However, the outbreak is likely to further impair those already struggling with poverty, vulnerabilities, and discrimination disproportionately.

According to the World Bank, 24 million fewer people will escape poverty in Southeast Asia this year as a result of the unprecedented economic shocks caused by the pandemic. Furthermore, in a worst-case scenario, an additional 11 million people will fall into poverty, defined as living on US$5.50 or less per day.

The report also stated that economic growth in the East Asia and Pacific will stall and ASEAN member states Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand will all see negative growth.

“Countries in East Asia and the Pacific that were already coping with international trade tensions and the repercussions of the spread of COVID-19 in China are now faced with a global shock,” said Victoria Kwakwa, the World Bank’s Vice President for East Asia and the Pacific.

ASEAN has made numerous efforts to reduce poverty and several schemes have appeared to be successful. Some examples include Vietnam’s commitment to education reform, Singapore retraining and reemploying older workers and the Philippines’ 4Ps programme which has been lauded for lifting millions out of poverty - increasing school enrollment and improving health and nutrition.

Nevertheless, there is still a long way to go and much more needs to be done as millions are still struggling in the region.

In the wake of the pandemic, many have lost their jobs and more will lose theirs as a result of drastic measures to contain the virus such as nationwide lockdowns. But the worst suffering could be informal workers, “people who are… invisible and very hard to go identify, find, and help,” said Aaditya Mattoo, the World Bank's Chief Economist for East Asia and the Pacific.

As of 22 June, over 132 million people have been infected across ASEAN member states, with Indonesia and the Philippines having the highest number of active cases in the region.

The Philippines has made great progress in combating poverty over the years. The poverty rate in the country decreased from 21.6 percent in 2015 to 16.6 percent in 2018, and is projected to decline further in the coming years. But poverty is still a major problem and the health crisis is an additional burden for impoverished families and those living in urban slums. Last year, it was reported that about one in five of the country’s 106 million people lives in extreme poverty.

Many of the Philippines’ slum dwellers are informal workers. Therefore, it was not a surprise that when President Rodrigo Duterte declared a citywide lockdown in mid-March – many lost their jobs and struggled to find sources of income to survive.

Over in Indonesia where 24.79 million people are considered poor, things have never looked bleaker. The country has more than 46,000 COVID-19 cases since the virus first appeared in the archipelagic nation – and total deaths stand at 2,500 as of 22 June, the highest in the region. But observers believe that the actual figure could be higher than what is officially reported.

Poor Children

Save the Children and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recently revealed that without urgent action, the number of children living in poor households across low- and middle-income countries could increase by 15 percent, to reach 672 million this year.

“The coronavirus pandemic has triggered an unprecedented socio-economic crisis that is draining resources for families all over the world,” said Henrietta Fore, UNICEF's Executive Director.

“The scale and depth of financial hardship among families threatens to roll back years of progress in reducing child poverty and to leave children deprived of essential services. Without concerted action, families barely getting by could be pushed into poverty, and the poorest families could face levels of deprivation that have not been seen for decades.”

The organisations warned that the immediate loss of income means families are less able to afford the basics such as food and water, health care or education. Some parents who have lost their jobs could even allow their children to work to earn some extra cash for their families. Some of them would perhaps be at risk of child marriage, violence, exploitation and abuse.

Related articles: